What drives the creative impulse? Is it a reaction to the world, or an attempt to create new worlds? Human nature, or human ambition? French artist Jean-Luc Moulène takes a Descartian stance; he says, “To create is to embody a thought.” The lead up to his long-awaited and first solo exhibition in Australia has taken much thinking, and much communicating, working with a team of people across the world to create Jean-Luc Moulène and Teams.

“The exhibiting works span existing pieces and four newly commissioned sculptural objects that were created in Australia, using Australian materials and technicians.”

The teams are varied. Moulène himself lives and works three hours outside of Paris; Mona commissioning curator Olivia Varenne is based in Geneva; guest curator Michel Blancsubé lives in Mexico; and Mona is, of course, in Hobart. The project was first conceived in 2018 and was intended to be exhibited in 2020, then 2021, and is now finally coming to fruition. The pandemic resulted in delays, but the delegatory nature of Moulène’s creative process was already in place.

“It was the experience of entrusting the teams not only with the exhibition but with the works,” says Moulène. “It was a question of distance and time. Then, the coronavirus pandemic came and gave a new necessity to this question because I couldn’t be present anyway.” Mona curator Sarah Wallace agrees, explaining, “Even pre-Covid, when the project was first conceived, we always understood that Moulene’s delegation of artistic authority is essential to his practice.”

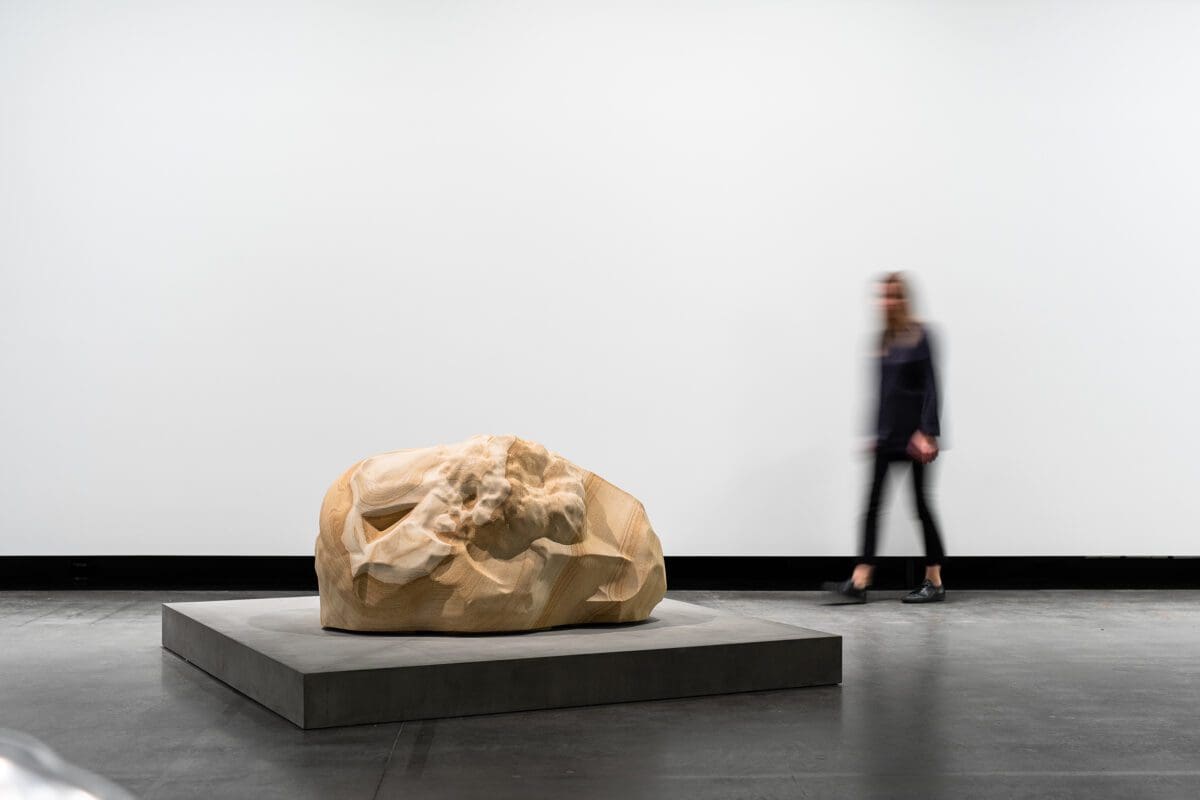

The exhibiting works span existing pieces and four newly commissioned sculptural objects that were created in Australia, using Australian materials and technicians. One is made with wax, another metal, the third Triassic sandstone, and the final timber from primaeval Tasmanian underwater forests.

“The sandstone sculpture, though made to precise specifications, looks like it could have formed naturally over years of careful erosion.”

“The materials are specific to the location,” says Wallace. “Each material was selected by Moulène and then totally transformed. His ideas always evolve from a deep and considered engagement with material form and process, and then he worked closely with our teams at Mona to create these works.”

The objects Moulène has created throughout his career differ greatly in style. Some have an artificial and playful manner, from a scythe attached to a plastic chair, or a blender replacing the lens of a camera. But these new works have an earthen quality, largely due to the materials used. The sandstone sculpture, though made to precise specifications, looks like it could have formed naturally over years of careful erosion.

Moulène himself downplays the intention of the materials, instead focusing on the collaboration. “The materials used for these new works, produced in Australia, could be found everywhere,” he says. “There is wood and stone worldwide, but producing locally is the specific pleasure of making, and also the pleasure of meetings, of creating new teams for one time, one project.”

In another room of Mona is another international artist. They are also recreating the natural world, but through a purely sensorial experience: Icelandic musician and visual artist Jónsi has created the sensation of being in the belly of a volcano.

“Hrafntinna (Obsidian) is the result. Visitors enter a dark room, first encountering the smell of fossilised

amber.”

The impetus came from the 2021 eruption of Fagradalsfjall in Iceland, which had lain dormant for 800 years. Jónsi was in the United States at the time, unable to leave due to the pandemic. Restricted to watching videos shared by his friends and family, who witnessed the eruption from a safe distance, was frustrating. “I really wanted to see it and experience it, to smell it,” says Jónsi. “I wondered, ‘How can I create a volcano?’”

Hrafntinna (Obsidian) is the result. Visitors enter a dark room, first encountering the smell of fossilised amber. “It has a sweet and smokey tar-like smell,” says Wallace. Next come the soundtracks: a mixture of haunting hymns and choral pieces accompanied by abstract soundscapes and bass lines that reverberate bodily, played through 16 channels and 195 speakers that encircle the visitor. The experience lasts 25 minutes and includes a ‘secret’ element that Mona is waiting for audiences to discover themselves.

Such soundscapes are to be expected from the musician, who’s band Sigur Rós is one of the most famous Icelandic exports since Björk. But the olfactory sensation is another passion of Jónsi’s. Wallace describes how he began experimenting with essential oils and aroma chemicals in 2011, and would carry around a portable perfume kit on tour. In 2017 he co-founded a perfumery in Reykjavik with his family, and has been increasingly incorporating scent into his practice.

“Most of his installations and sculptural assemblages are grounded in sensory experiences,” says Wallace. “They all combine, in some way, visual, auditory and olfactory senses.”

For Jónsi, the non-visual senses possess the ability to transport us. “Despite their invisibility, scent and music have so much capacity to make us feel,” he says. “They engage us physically, trigger us physically, while simultaneously allowing our minds to wander through memory, and across landscapes.”

Jean-Luc Moulène and Teams

Jean-Luc Moulène

Hrafntinna (Obsidian)

Jónsi

Museum of Old and New Art

(Hobart TAS)

30 September—1 April 2024

This article was originally published in the September/October 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.

Please note: In the September/October print version of this article we incorrectly titled the gallery name, which should read Museum of Old and New Art (Mona).