Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

From marble busts and intricately detailed paintings to the humble iPhone selfie, humans have had their likeness depicted in portraits since the form flourished in ancient Egypt over 5,000 years ago. At times, portraiture has been seen from empowering to humbling—but the form also speaks to whose image we value and why. And it’s these urgent aesthetic and social questions that contemporary Australian artists are navigating.

During the 14th century, Renaissance Europe was a nucleus for portraiture, often commissioned by wealthy patrons to convey their physical appearance, status, family crests and property assets. Containing visual markers specific to their time, these portraits give us information about life, and how people were living it.

Yet this is also a thin slice of life. Once reserved for royalty, the upper classes and religious icons, portraits are now prolifically available on a global scale. Almost primordially, we desire to see our likeness represented visually. Portraits convey who we are and where we come from, how we are perceived and how we want to be perceived, and where we belong. While conceptual and non-figurative art may have reigned during the 20th century, contemporary Australian artists are—at this very moment—creating and expanding portraiture. We have returned to the figurative, but it begs the question: why do portraits still resonate?

Looking at Australian portraiture in the last century, one of the most significant evolutions is who is in the portrait. Visiting an exhibition of official portraits in the early 1900s, one would most likely see a ‘who’s who’ of bearded white men with stern expressions. Women artists were indeed producing excellent work, but it is well established they were not given the public visibility of their male counterparts.

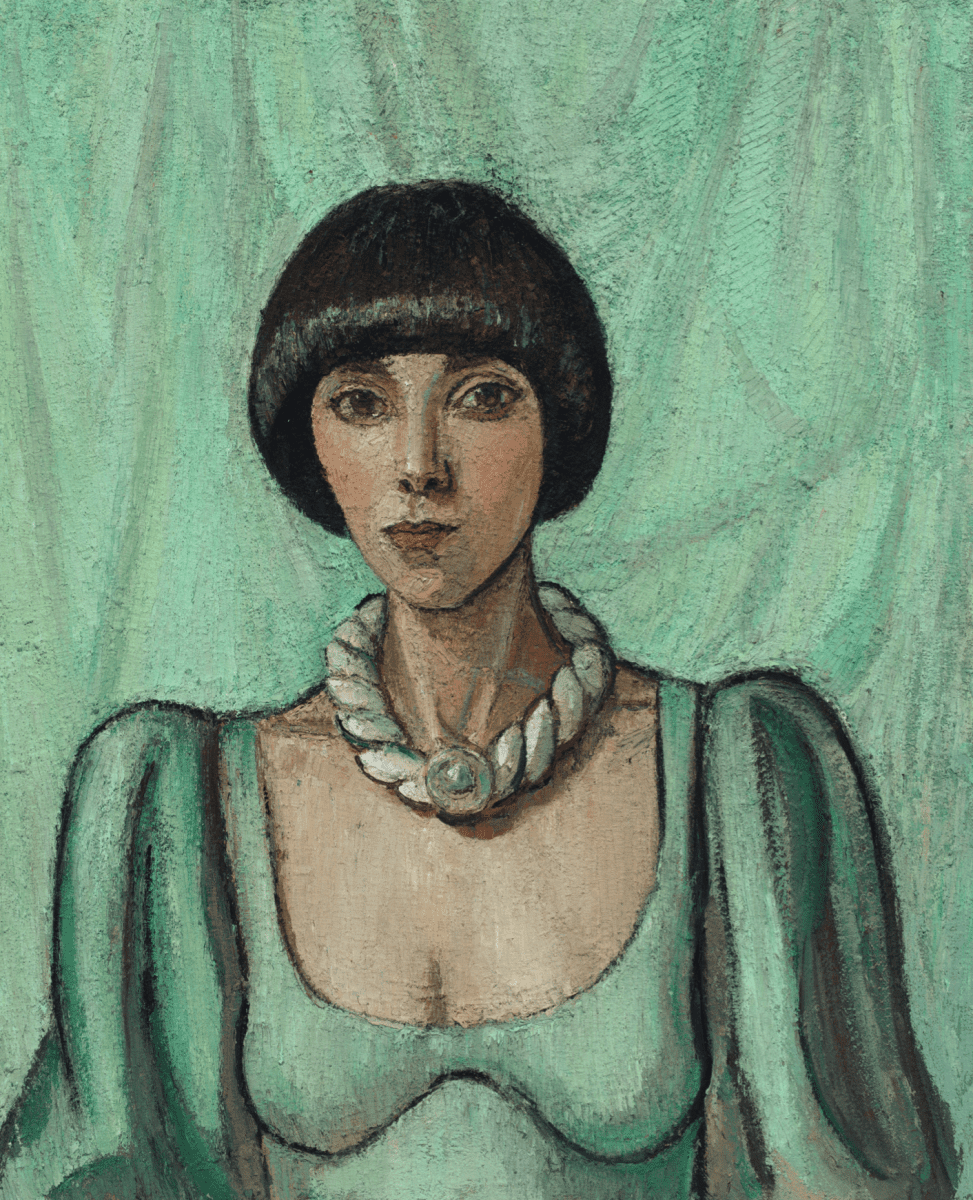

Artists like Grace Crowley and Nora Heyson were painting striking portraits celebrating women as independent individuals rather than as submissive objects of beauty so often depicted by the male gaze. Spurred by the increasing public visibility of women, led by societal shifts like the suffragette movement and gendered occupational changes in World War I, women slowly began appearing more frequently in portraits and art awards like the Archibald Prize—a reflection of their changing status in society.

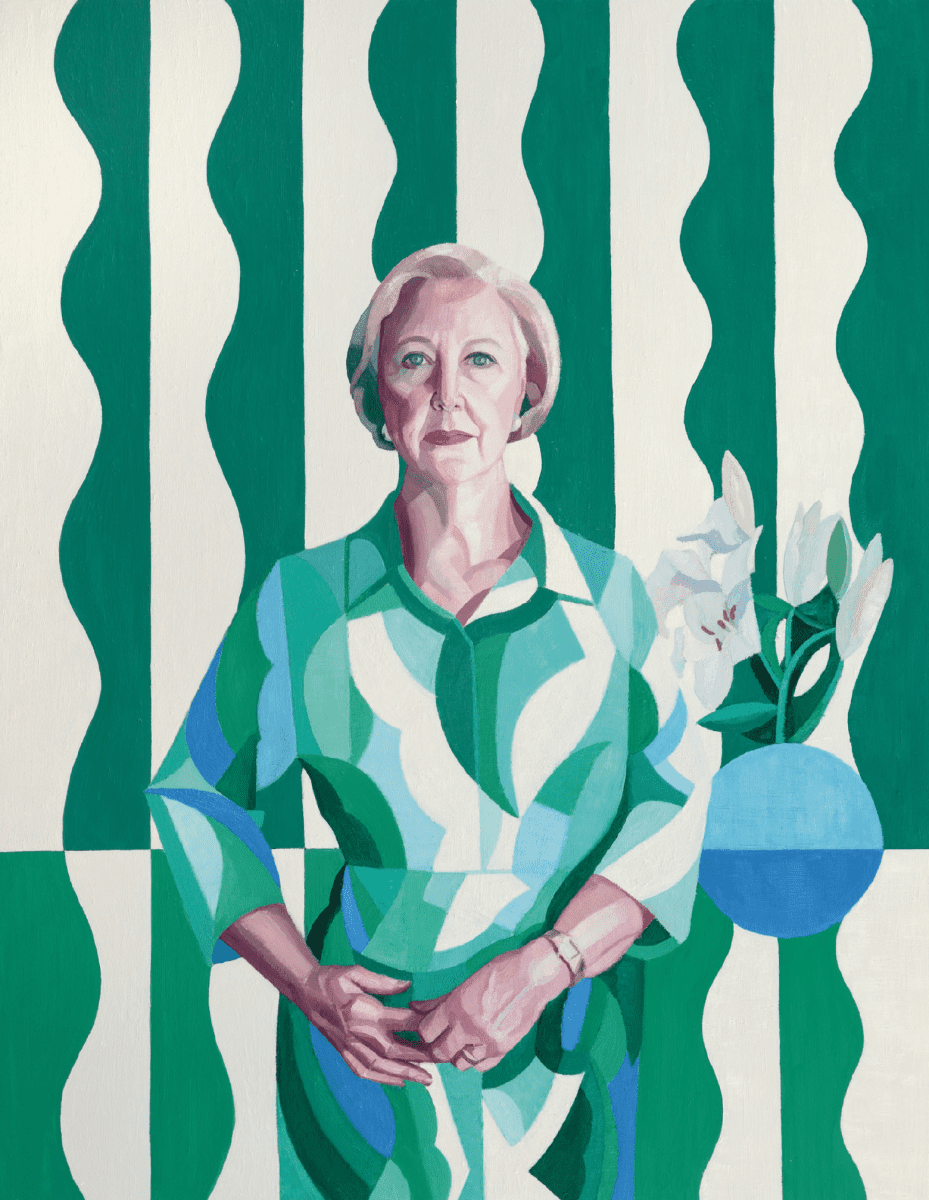

Today, almost a century later, Melbourne-based artist Yvette Coppersmith has been painting portraits for nearly two decades. Focusing much of her practice on women and the female gaze, self-portraits feature consistently. She has also painted portraits of women in positions of influence, most notably former president of the Australian Human Rights Commission, Gillian Triggs. For Coppersmith, portraiture—the question of who is being legitimised by the form—is a vehicle for activism and political change.

She speaks of the connection between painter and subject, and the importance of who an artist chooses to depict. “Painting a portrait is an exchange between the artist and the sitter. There is a power dynamic there—in my work it’s the female gaze.

It’s about shifting the power of who you would expect to hold power in the art world. The space for expanding the narrative of representation is important too.”

In 2018, Coppersmith became the tenth woman to win the Archibald Prize for her painting, Self-portrait, after George Lambert. Female representation as both artist and subject in prizes like the Archibald is improving. Even more significantly, Indigenous artists and artists of colour are becoming prevalent subjects, finalists and prize winners in contemporary Australian portraiture. As writer Jennifer Higgie pointed out in a 2021 conversation for Literary Hub, “Cultural critics and art historians aren’t just looking at the exclusions of women, they are also looking at the exclusions of people of colour, of people of different abilities, of people of different class. It’s very clear that art history is a work in progress.”

Visibility in the public consciousness is key and Coppersmith cites artists like Gordon Bennett, Julie Dowling, Daniel Boyd, Vincent Namitjira, Juan Davila and Nora Heysen as driving transformations in Australian portraiture—both formally, and for who they choose to paint. “To have more diversity visible is one of the most empowering things you can do for people,” she says. “You open the imagination of others. That’s the power of portraiture. People need to be able to see themselves reflected as it opens a space of possibility and change.”

Also based in Melbourne, artist Kate Beynon maintains a multidisciplinary practice that dips heavily into portraiture. A Hong Kong-born artist with Cantonese-Malaysian, Welsh and Nordic ancestries, Beynon incorporates fragments of cross-cultural identity, personal history and the supernatural into her portraits.

In the self-portrait Hybrid Self with Kindred Spirits, 2019, Beynon paints herself surrounded by otherworldly creatures reminiscent of mythological animals. By visualising ancient stories and characters through a contemporary lens, she says she paints these portraits to, “explore a sense of self, family and identity, navigate challenging times and inhabit in-between spaces. My work is also connected to feminist thinking and ideas of kindred spirits coming together.”

Sandra Bruce, director of collection and exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, is intrigued by how contemporary artists go beyond traditional modes of portraiture to “tell the stories of their subjects through their own visual language”. Expanding into methods of portraiture like sculpture, video and installation, the portrait is no longer limited to conventional ways of image making. “One outcome of this is a continuing blurring of the lines between portraits, figuration, conceptual work, and non-figuration,” says Bruce. She points to Yankunytjatjara artist, Kaylene Whiskey, as an artist who does this exceptionally well. Known for creating vibrant paintings celebrating strong women and Aṉangu culture, Bruce says Whiskey, “has reinvigorated the tradition of incorporating overt symbolism within her practice, fully embedding such literal visual mechanisms throughout her signature style: one that is truly contemporary”.

Like Beynon and Whiskey, Melbourne-based artist and writer Atong Atem has developed a distinct visual language to represent her experience of living in Australia. For Atem, this is heavily influenced by African diaspora and her experience of arriving in Australia as a refugee from South Sudan. While studying at university, Atem was unable to find images in art history reflecting her experiences. To remedy this, she began taking photographic portraits of herself and her community, actively adding a new voice to the dialogue of Australian portraiture.

Resplendent with visual storytelling, Atem’s images weave together science fiction, fashion and cultural identity, and are stylistically informed by the studio portraits of African artists Malick Sidibe, Philip Kwame Apagya and Seydou Keita. She says of her self-portraits, “My practice has been about using photography as a means of exploring history, and specifically the history of visual language and representation. A lot of the history of portraiture seems to me quite similar to the history of still life painting and photography. For example, the way that objects are imbued with meaning due to their historic associations.” The recipient of the inaugural La Prairie Art Award, Atem’s photographic series, A yellow dress, a bouquet 1-5, 2022, challenges historical and colonial narratives of migration and movement, reflecting these ideas through self-portraiture imbued with elaborate make up, costume and bouquets of flowers from varied locations.

As Coppersmith points out, the potency of portraiture as a vehicle to drive systemic change lies in how we visually depict ourselves and others. “There’s no more lasting document than a piece of art. A work of art is going to outlast other media. Newspapers might be archived but we don’t go back and look at them in the same way as something in an art gallery.” Speaking about the Archibald, she describes the award as “a barometer of how conservative Australia was and how far we’ve come”.

Coppersmith continues, “For Blak Douglas to win this year with a portrait of Karla Dickens represents such a shift. It represents a change in conversation about national identity. There is power in having the Archibald audience. It’s huge, almost as big as a sport. It has the media attention to be able to harness that and direct the conversation where it needs to go.”

An artist who refuses to shy away from assertive truths, 2022 Archibald winner and Dhungatti artist Blak Douglas has been using portraiture as a form of activism for almost a decade. Criticising the lack of Indigenous representation in prizes like the Archibald, Douglas says, “Portraiture in Australia serves to uphold an ingrained conservatism in institutions. My first successful entry as a finalist was in 2015 with a portrait of Uncle Max Eulo and up until that year, 90% of past Archibald finalists and victors had been white male faces. Within my era, Craig Ruddy set the cat among the pigeons in bureaucracy with his Archibald winning portrait of David Gulpilil in 2004.”

Portraits are not Douglas’s usual way of working, and yet each year he produces a painting of a prominent First Nations figure with the sole purpose of entering it into the Archibald. A five-time finalist, Douglas won the 2022 award with Moby Dickens, a three-metre-high painting of Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens carrying buckets of water through a flooded landscape. Looking closely, one can see the buckets have holes and storm clouds brew over a landscape inundated with muddy water.

As a historical document, Douglas’s portrait communicates multiple issues—the lack of government support for artists, climate change, financial insecurity and social injustice. Douglas says, “Fundamentally this work is as ripe with metaphors as the government is with corruption. That’s where the Blak Douglas style of work comes from, there’s an aesthetic enticement and then it sucker punches you.” When Douglas won the award, it was the first time an Archibald winning painting had both an Indigenous artist and sitter.

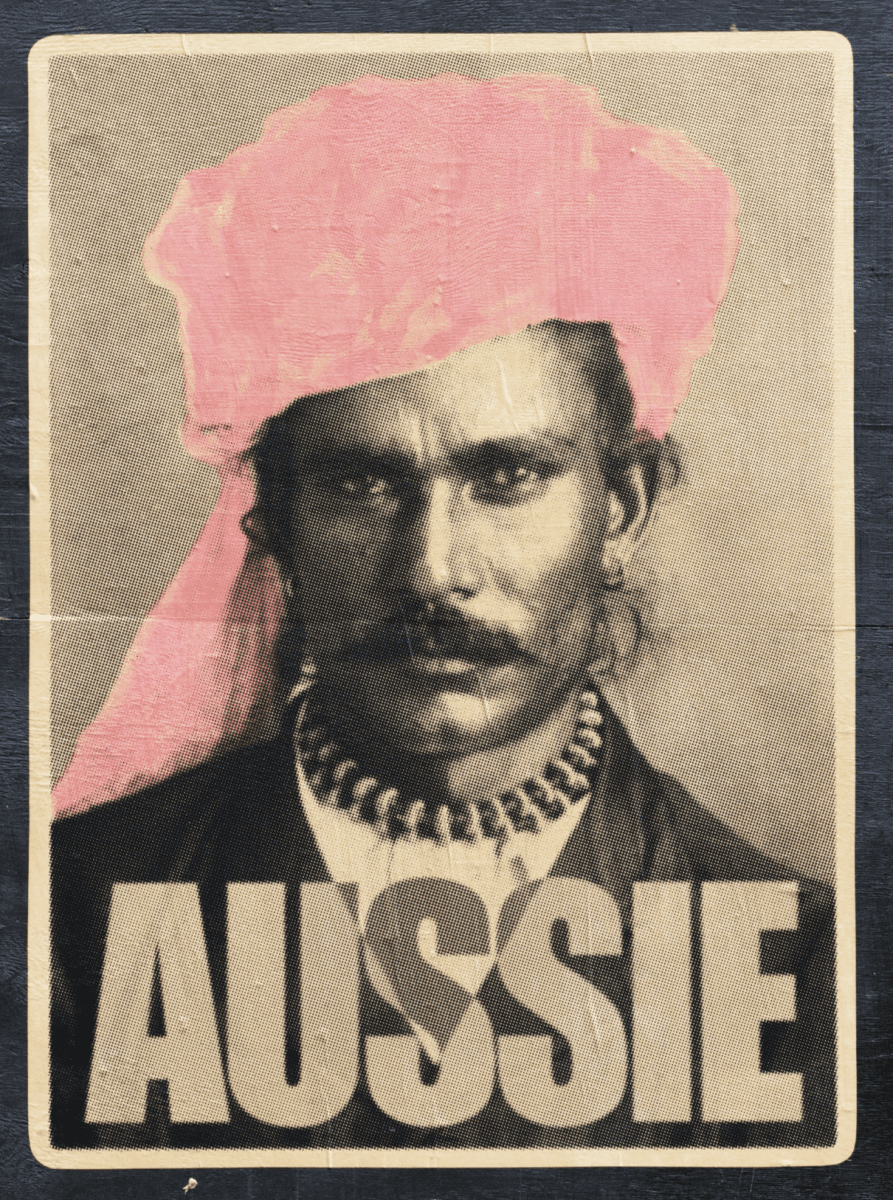

Stepping outside the gallery and taking portraits to public spaces is South Australian artist Peter Drew. In his AUSSIE poster series, Drew uses photographs from the Australian National Archive that capture people oppressed by racial restrictions of the White Australia Policy (introduced in 1901 by parliamentarians to curb immigration).

Despite many being born in Australia, most of the men, women and children depicted in the AUSSIE posters were historically deemed to be a nationality other than Australian due to their perceived ethnicity. Through this project Drew challenges the viewer to think deeply about what it means to be ‘Australian’, and preconceived ideas of national identity.

With the potential to influence how we perceive others and to generate political change, unlike any other medium, portraiture reflects our past and our aspirations. The history and transformations of the form lay bare how much has changed—and how much hasn’t.

Despite—or perhaps because of—their ubiquity, portraits are still among the most recognised forms of art across the globe. Is it at all surprising Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa—a portrait—is the most famous artwork in the world? Perhaps the answer lies in our inherent human need to be seen. To record our lived experience and the issues facing humanity at this moment in time. Seeing ourselves reflected ultimately brings us closer together by revealing a shared humanity, always reminding us that we are not alone.

Yvette Coppersmith and Blak Douglas are showing in the Archibald Prize 2022 tour at Blue Mountains Cultural Centre (until 4 December) and Grafton Regional Gallery (17 December—29 January).

Kate Beynon is showing in Tell Me A Story at Hawthorn Town Hall Gallery (until 17 December) and Archie100: A century of the Archibald Prize at Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (until 8 January 2023).

Atong Atem is showing in WHO ARE YOU: Australian Portraiture at National Portrait Gallery (until 29 January 2023).

This article was originally published in the November/December 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.