In the early 2000s, towards the end of her life, American painter Agnes Martin penned a handwritten list for her monograph, which reads: “I have worked: in a factory. In a hamburger stand. As a receptionist. In a butcher shop. In a nursery. In a cafeteria. As a baker’s helper. As a waitress many times. As a dishwasher three times. As a janitor once. As a cook once. In a parking garage. Packing ice cream. As a tennis coach. On a farm, milking. As a janitor…”

It stretches to 35 other such jobs, an unusual biography for someone who garnered success in the art world. Martin’s transcendently poignant planes of paint have now come to typify mid-century Abstract Expressionism, hanging in the world’s lauded art institutions. And yet, Martin’s success did not come without sacrifice; she also lived for many years in a self-built, mud-brick structure in the Taos desert of New Mexico, without electricity or running water.

I often contemplate Martin’s list because it is a stark reality for so many of us who create, and who endeavour to make art their life’s work. A second job is often the crux of an artist’s livelihood as financial insecurity is still a (largely) unspoken sacrifice, which many are oddly willing to make.

I have a list reminiscent of Martin’s. As an artist I have worked: in an art supply store. As a nanny. Sewing clothing. Proofreading. Polishing jewellery. As an assistant. Babysitting. Doing data entry. Re-selling vintage clothes. Designing graphics. Taking pictures. Hosting workshops. Organising exhibitions. Wiping bottoms. Cooking dinners.

“I know I’m not the first woman who has had to grapple with the realities of establishing a comfortable career in the arts—most of my creative friends are in the same boat. I know a painter who washes other people’s dishes during the day and paints on cloth by lamplight at night.”

These part-time roles have financially sustained me while pursuing a career in the arts, interwoven into a life of making do. However, to my dismay, the dreams which once burned so brightly are beginning to taper off as I face the realities of a future where decisions like motherhood and a mortgage cannot likely be sustained on the income of a creative practitioner. What happens when the trope of the starving artist becomes all too real, and the accompanying sacrifices and stresses of pursuing a creative career alienate you from your own practice—and from health and happiness, too?

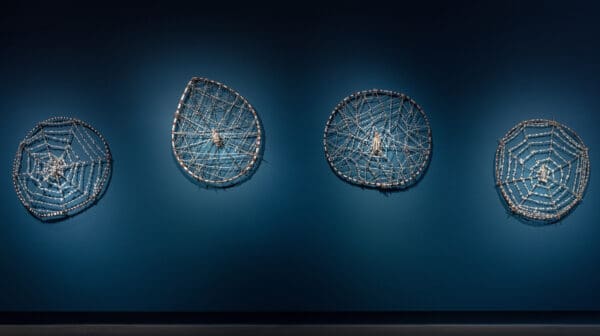

I know I’m not the first woman who has had to grapple with the realities of establishing a comfortable career in the arts—most of my creative friends are in the same boat. I know a painter who washes other people’s dishes during the day and paints on cloth by lamplight at night. There’s the sculptor who bicycles to the studio in stiff mid-winter air and spends a third of his weekly support work paycheque on the purest pigments of blue. I consider the unemployed poet who circles a figure eight through the local park, his workplace: the world. The painter who straddles three jobs, plus study and the needs of a small child, whose subject matter is domestic calm in the eye of a demanding storm. The photographer who shapeshifts into a law secretary between the hours of 9am and 5pm, later committing to the darkness required for exposing pictures in silver nitrate, by gloved hand. These are not uncommon stories.

“Creatives swim in a small pool, jostling for a handful of opportunities, which makes it increasingly difficult to sustain meaningful part-time employment alongside a creative practice.”

Most of the artists I know exist in two necessary realms, the day job and the night job, moonlighting as our true selves when time and resources allow it. We learn to be frugal, to juggle responsibilities and deadlines. But despite popular belief, no one can survive on self-expression, monastic obsession, or an intense desire to put paint on canvas. Perhaps the romanticised fallacy of the starving artist has led us to believe that artists do not require much more in life. How wrong this misconception is, and dangerous too.

Scrolling once again through job-searching site Seek, I noticed that the job growth projection for Australia’s creative industries is a depressing 0.8% over the next five years. Seek currently displays a mere 280 arts positions nationwide (and some of these are misplaced roles, like “Sandwich Artist” at Subway). Construction counts 6,887 jobs, education has 14,227, and healthcare boasts 22,883.

Creatives swim in a small pool, jostling for a handful of opportunities, which makes it increasingly difficult to sustain meaningful part-time employment alongside a creative practice. Not to mention a focus purely on arts training can often leave one under-skilled in positions where other kinds of proficiency is essential.

It is important to remember that artists are workers, even though arts and design workers are not protected by unions. The struggle to secure superannuation, sick pay, award wages and career stability is enough to drive hopeful arts workers to defect to other industries to protect themselves and their livelihoods. The consequence is that arts industries are drained of precious knowledge, skills and niche expertise.

The artist friends I mentioned earlier make art because they love it. As do I. We couldn’t imagine leading lives in which making things with our own two hands wasn’t a central force—but it’s also an uncomfortable reality when your paintings hang in the kinds of homes that you could literally only dream of inhabiting. Artists work hard to create cultural capital, and yet they can barely afford to indulge in it themselves.

Thinking again of Martin, surviving on odd jobs and painting with her back to the world, and without romanticising that trope further, I realise that “making it” as an artist in this lifetime might just be the oddest job of all.

Caitlin Aloisio Shearer is a painter and illustrator who also works for Art Guide Australia.

This article was originally published in the September/October 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.