Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

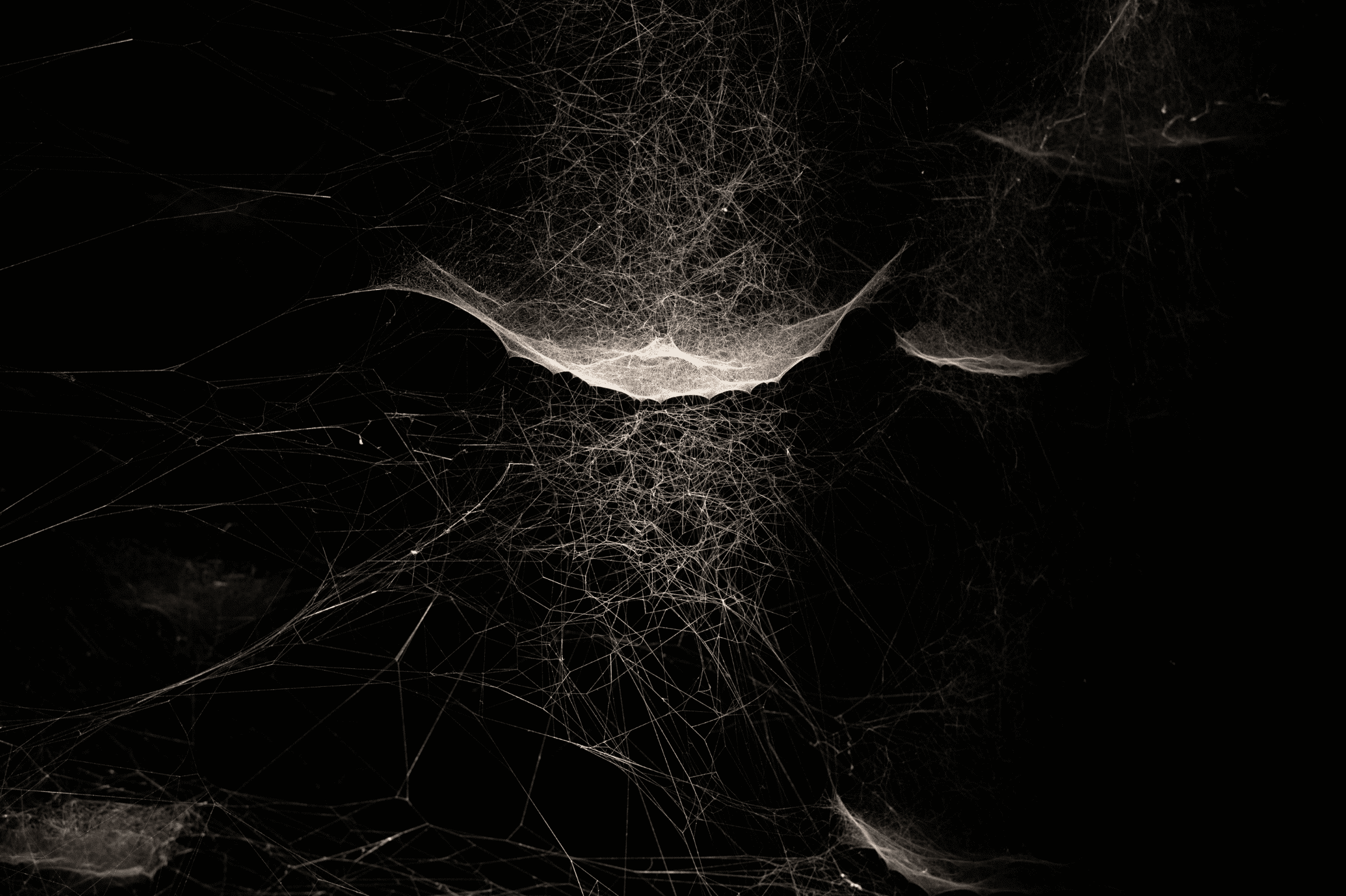

In this web of life, Argentinian-born, Berlin-based artist Tomás Saraceno suggests humans have a lot to learn from animal bioindicators: the notion that we might better understand climate through changes of behaviour in various species.

Ants, for example, make their way into our homes when the rain is heavy outside. Dogs are known to have acute hearing and smell beyond human range. Bees see the world partly through a combination of yellow and ultraviolet light known as ‘bee’s purple’, invisible to humans. Insects, arachnids and certain other animals share communal knowledge of survival, suggesting Western society can learn from such knowledge in the natural world.

Saraceno, born in San Miguel de Tucumán in 1973, recites a proverb in Italian—and then in English—that he remembers hearing as a child after his family of five lived in exile in northern Italy for several years, having fled the military dictatorship during Argentina’s Dirty War (1974 to 1983). It goes: “When the clouds appear like sheep, the rain will come soon.”

Science informed Saraceno’s childhood, but so did the wonder of spider webs in the family attic. His father, who had spent nine months in jail in Argentina before the right-wing coup in 1976, was an agronomist; an expert in soil and crops. His mother, a botanist working on the morphology of plants, would press vegetation samples between the pages of books.

Their artist son came to understand more ways of seeing the world than Western scientific encapsulations, or the Western centring of individual consumers in the “Capitalocene”: the exhaustive extracting of fossil fuels and the toxifying of the air, causing a much higher mortality rate among the world’s poor.

Sporting a beard and bold, red-rimmed spectacles, Saraceno asks now: “What happens if you fold a leaf?” He holds his hand aloft, curls his fingers, and turns the hand over, talking about “veins and nerves and filaments”, and variegations in colour. “Then you see the other side of the leaf—you know what I mean, as a metaphor?” That other side, Saraceno suggests, could be adopting the Indigenous practice of controlled burning, to help country regenerate and flourish.

Having studied architecture in Buenos Aires, and moving to Germany’s Städelschule in Frankfurt to complete postgraduate studies in art and architecture, where he opened his first studio in 2005, Saraceno often speaks in metaphoric poetics. Meanwhile, his desire to “render visible” other cultures’ and species’ connections to the natural world results in projects combining the practical with the wondrous.

In 2019, for example, in a small village in Somié, located in Cameroon near the northern border with Nigeria, he collaborated with spider diviners. This resulted in a website (nggamdu.org) where binary ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions can be asked to the grounddwelling spiders, with questions written on cards produced from stiff plant leaves.

“It’s very beautiful,” says Saraceno. “There’s a tradition of voodoo or a shaman who is able to communicate with spiders. They go up into the forest, where the spiders come out of their hole. The diviner translates the question to the spider by banging a stone on a piece of metal, because spiders talk through vibration, right?

“The spider [rearranges] these cards, and the diviner then interprets the answer. Sometimes the spiders are not so direct, which is unbelievable,” he laughs. “You can ask again and again.”

As part of Saraceno’s current multisensory show Oceans of Air at Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art (Mona), the artist’s team installed a series of intricate, hybrid webs, as the latest iteration of Saraceno’s international community research project Arachnophilia.

Given arachnida—the name given to joint-legged invertebrate animals like spiders and scorpions— have roamed the planet for some 280 million years, he philosophises that spiders possess wisdom to survive environmental catastrophe.

Having recently sustained a knee injury, Saraceno is nonetheless still hoping at the time of our interview—October 2022—to do the Wukalina walk in Lutruwita / Tasmania’s Bay of Fires, to have an encounter on Country with the Palawa people. “You go there, you spend time,” he says, keen to hear about Indigenous land management, having read Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu and Victor Steffensen’s Fire Country. “You have to hear much more than you have to say.”

Saraceno is always up for an adventure. In 2020 his Aerocene Foundation (a non-profit devoted to community building, scientific research, and artistic experience) flew a balloon powered by the sun, to promote the idea that “water and life are worth more than lithium”. In the Salina Grandes region of northern Argentina, local communities are fighting against industrial lithium extraction, which is used in phone batteries, because of the amount of water used.

The artist explains we must change our consumption habits. “Let’s stop buying the latest iPhone,” he says, adding governments should create laws to force tech companies to change parts in laptops and phones, rather than throwing away devices when battery power wanes.

Saraceno cites Oxfam figures from 2019 declaring the world’s 26 richest people own as much as the 3.8 billion people who make up the poorest half of the planet’s population (and the BBC reports that the world’s 10 richest men having since doubled their collective wealth in the first two years of the pandemic).

“Why don’t we talk about the maximum income people can have?” he says, shaking his head. “You see how unhappy these people are, how alone they are? We should pity those people; you know what I mean?”

Tomás Saraceno: Oceans of Air

Museum of Old and New Art (Hobart TAS)

Until 24 July

This article was originally published in the January/February 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.