The laws of physics allow us to predict with relative accuracy how something might behave. We know gravity will cause a heavy object to fall, at a certain temperature water will boil, and a tightly coiled spring will eventually release in a burst of energy.

For Italian artist Arcangelo Sassolino, accurately predicting how an object or material might behave has become an integral part of how he makes art. Starting out as a toymaker, Sassolino initially worked for Casio Creative Products in New York before returning to Italy to work as a marble sculptor in Pietrasanta. From there, his love of mechanics and technology bloomed into his current practice of creating large-scale kinetic sculptures that combine physics and aesthetics.

“Even when I was a child, I was attracted by three-dimensional work, spending a lot of time in the garage outside the family house,” Sassolino explains. “I was really attracted by the idea of creating things by myself. When I grew up, I patented a kind of 3D puzzle, and I started working for an American company. I was based in New York, where art is easy to meet. And I fell in love.”

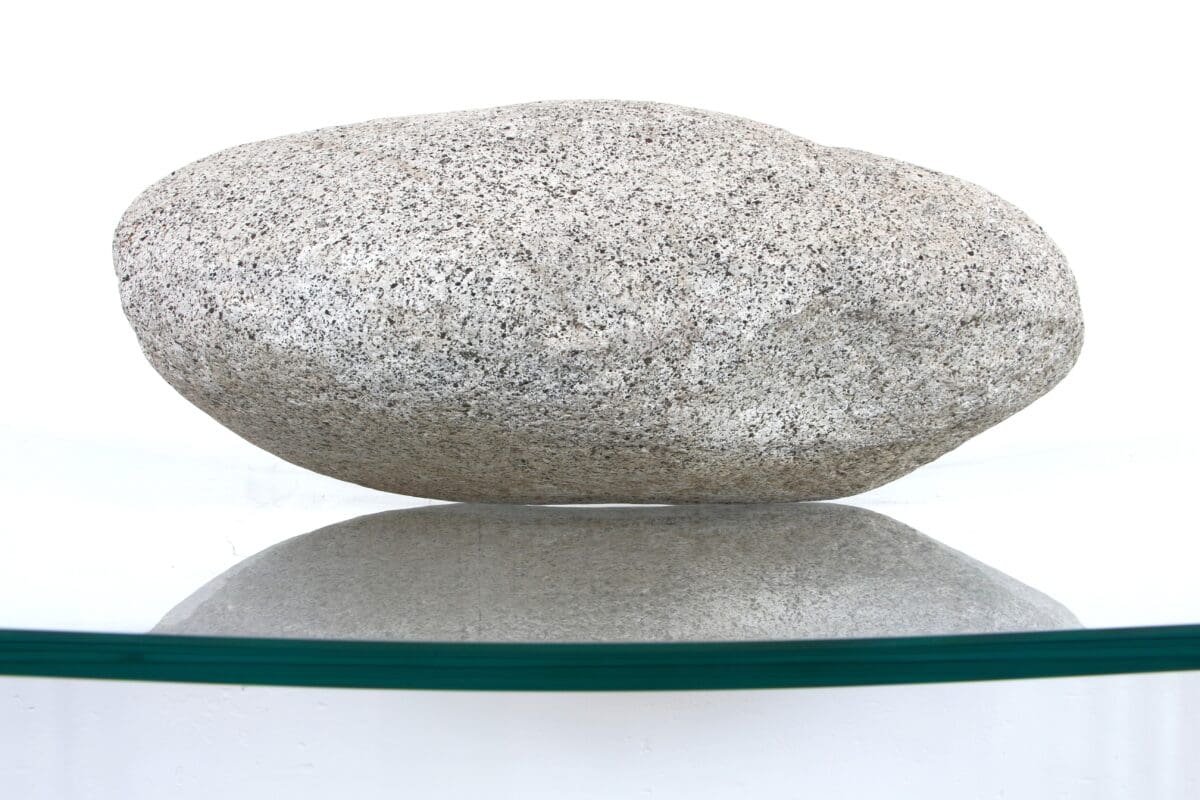

In his first solo exhibition in Australia, Sassolino brings five recent sculptures to the underground caverns of the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona). Here, the materials of wood, steel, glass and granite are coupled with custom built machinery delivering precise actions with extreme force. In marcus (2018), a black car tyre is tightly squeezed by a hefty metal clamp, causing it to look as though it might burst at any second, while the paradoxical nature of life (2025) displays a granite boulder precariously sitting in the centre of a glass slab. The glass is bowed beneath the weight of the granite and yet, somehow it all remains intact. Set to punch, squeeze or spin while we watch, each of Sassolino’s machines push sculpture to the limit, teetering between physical balance and catastrophic destruction. The physical tension is palpable.

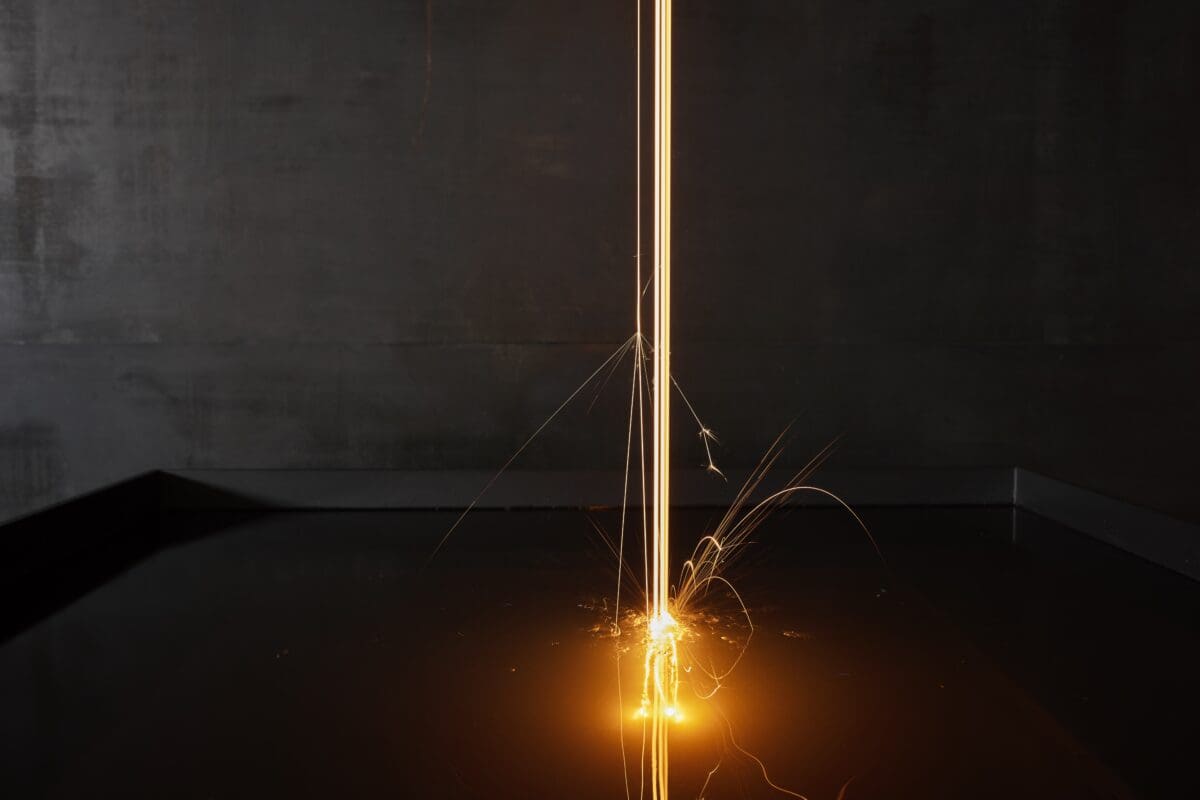

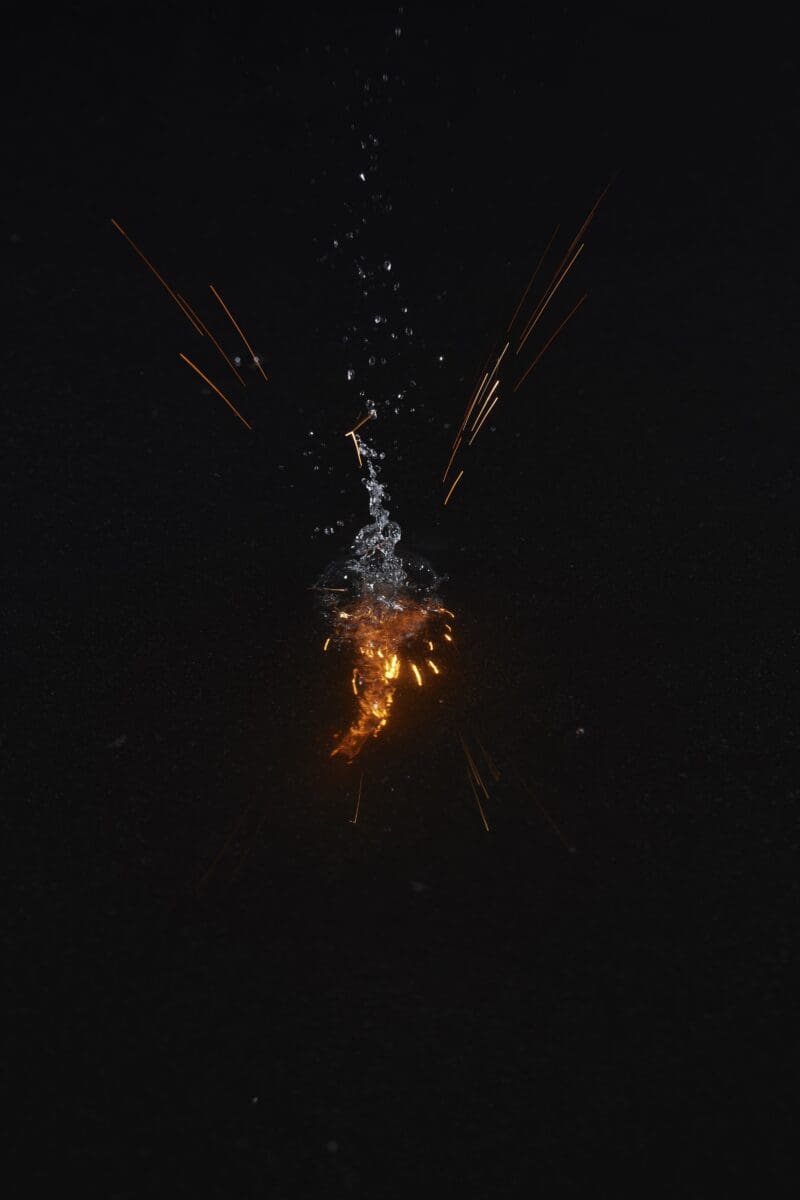

Cranking anticipation to the maximum, Sassolino has described his works as “psychological traps,” where the viewer’s attention is captured by a suspenseful action playing out before them. The title piece of the exhibition, in the end, the beginning (2025) is a reimagining of Diplomazija astuta (2022), a work Sassolino originally created for the Malta Pavillion at the 2022 Venice Biennale. In a darkened gallery, globs of molten steel (melted to 1500°C) slither from the ceiling to create a series of scorching spurts dripping into pools of water. Sparks fly and the air feels electric.

Sassolino originally intended the liquid metal to fall directly onto the floor and says the vast space Mona offers allows the work to be closer to what he first imagined for Venice. “Mona is a space that not only embraces the raw energy released by materials but also highlights how that energy dissipates into the surrounding space,” he says. Currently living and working in Trissino, a town in the province of Vicenza in Italy, Sassolino says the area he resides in is known for its excellence in industrial production and mechanics. As he explains, this deeply informs his work. “I come across what I call the urban delirium, the aesthetics of provincial chaos. A creative anarchy: self-propelled vehicles of all kinds, a forest of pipes, buildings of every colour and material. I don’t just see, I observe that hallucination; and it is projected inside of me. That’s why I, as an artist, transform and restore all this in sculpture.”

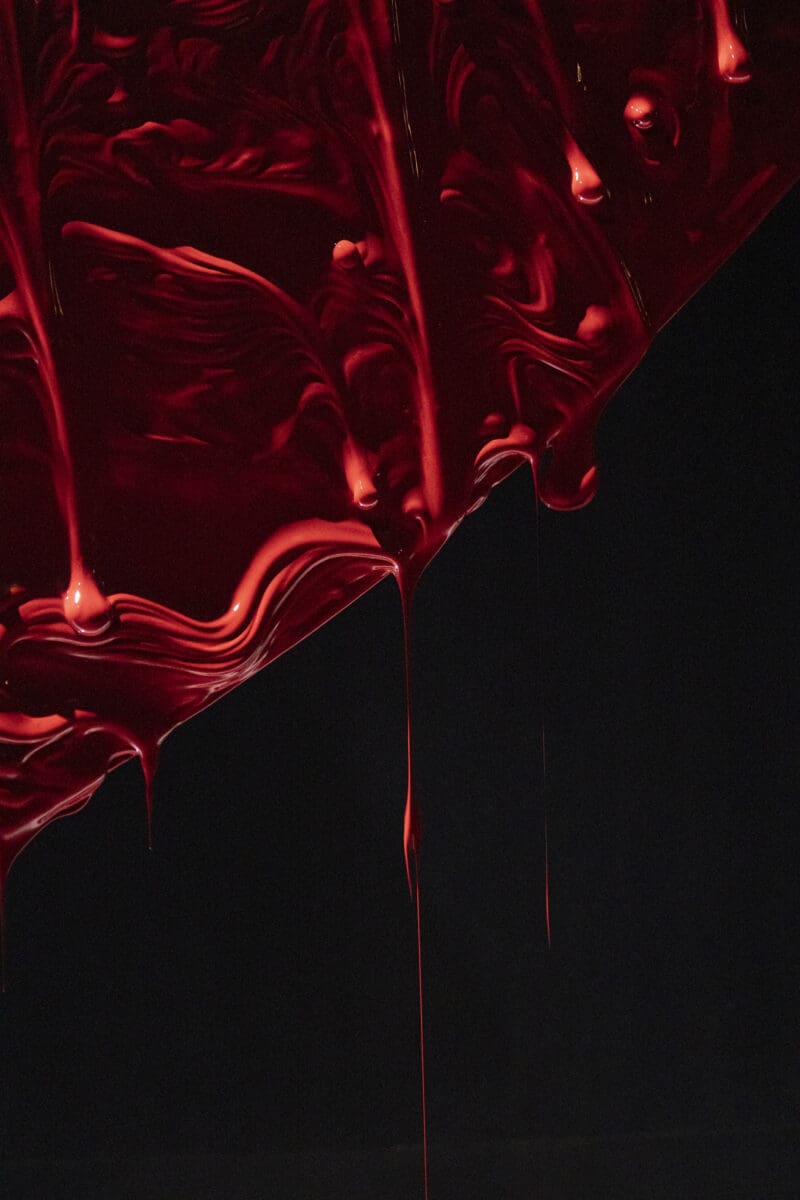

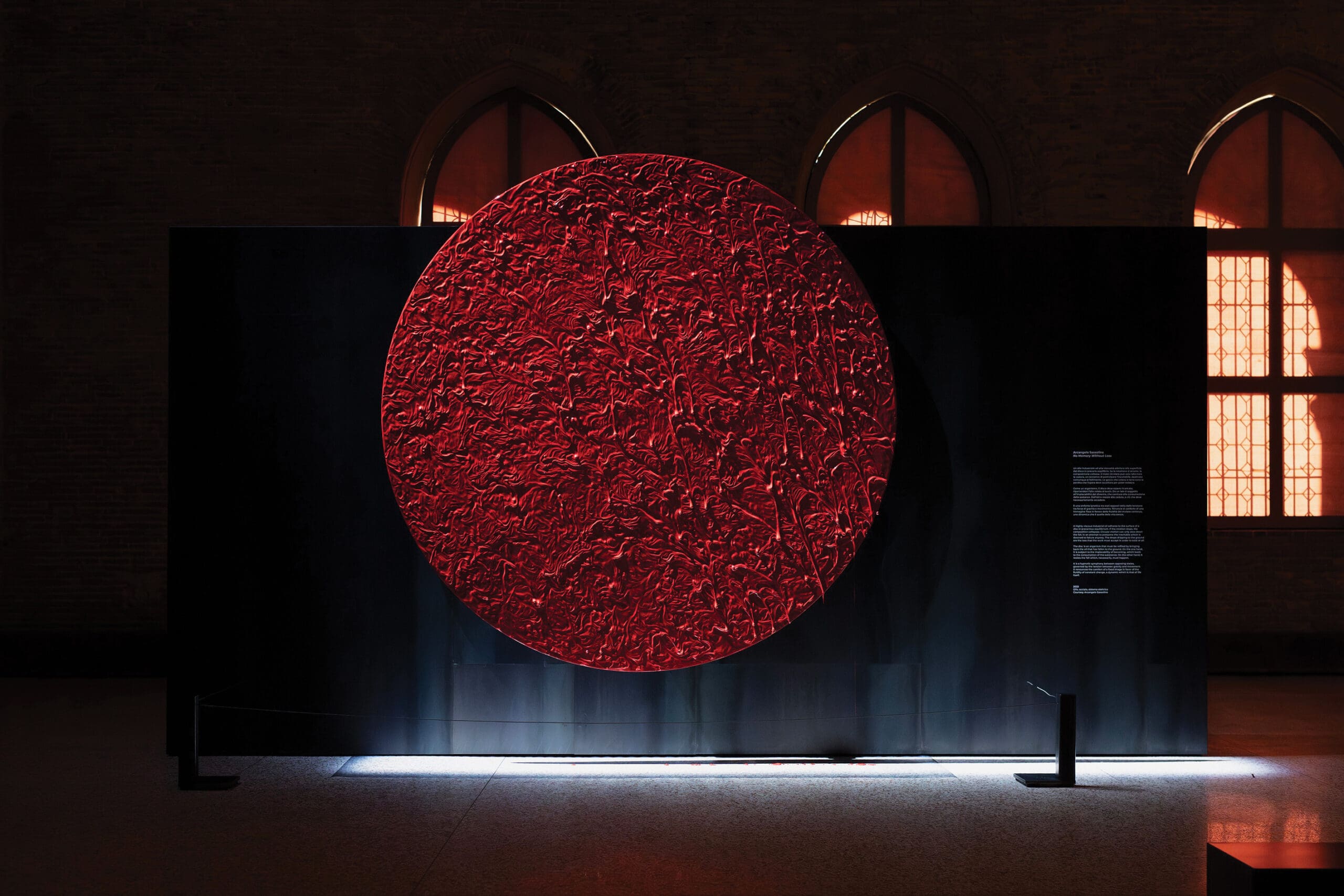

Taking in the exhibition, it is clear transformation and renewal are at the heart of Sassolino’s practice. Gracefully violent actions transform liquid to solid, wood to splinters or glass to shattered shards. In no memory without loss (2023-2025) the viewer is presented with a large spinning disc mounted onto the wall. It is covered in heavily applied industrial oil that creates a slow moving, wrinkled skin across its surface. On occasion, random drips of oil detach from the disc, resulting in a viscous sculpture that is constantly evolving. Violenza casuale (2008-2025) also relies on transformation as rectangular blocks of wood gradually crack and splinter under the force a hydraulic piston applies to their centre.

Mona is a fitting location for Sassolino’s work. In close proximity there are similar artworks that act in harmony. Every hour the industrial clanging of Jean Tinguely’s Memorial to Sacred Wind (1969) echoes through the museum, while nearby, the smell of engine oil emanates from Richard Wilson’s 20:50 (1987). With the site under near-constant construction, Mona’s sandstone guts are scraped and pierced with machinery not unlike Sassolino’s creations in the gallery. As Sassolino puts it, “Ideas are born from a bud. Sometimes they close, sometimes they blossom. When they blossom, it is extraordinary to see how one thing becomes something else, and then something else again, and opens possibilities that were initially obscure and hidden in the deep of the unconscious.”

Arcangelo Sassolino: in the end, the beginning

Museum of Old and New Art

(Hobart/Nipaluna)

On now—6 April 2026

This article was originally published in the July/August 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.