Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Sand is a material French artist Théo Mercier knows well. Creating life-size sculptures of industrial machinery, furniture, architectural ruins and animals, Mercier uses only sand and water to realise immense and intricate scenes of urban decay and contemporary relics.

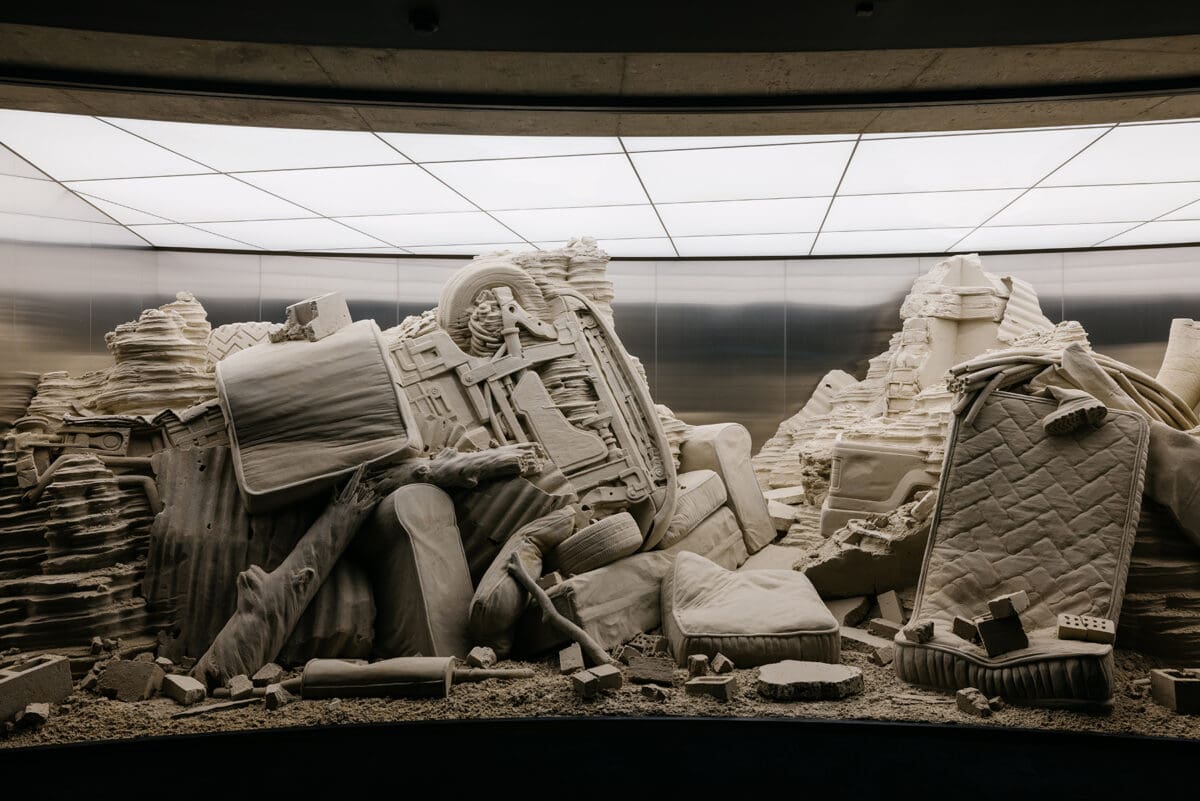

Exhibiting for the first time in Australia at Tasmania/Lutruwita’s Museum of Old and New Art (Mona), in MIRRORSCAPE Mercier explores how we process sites of trauma and disaster. He describes his sand sculptures as “the landscape of catastrophes”. As his fifth sand sculpture following recent exhibitions in Europe, MIRRORSCAPE features trucks and cars upturned, their torsos and mechanical debris appearing as though brutally swept away in a landslide or tsunami, until they have come to rest in the corner of the Round House (once occupied by Mona’s library), all their chaotic movements frozen in time. Mimicking the forms and textures of local sites displaying geological erosion, Mercier’s scene of destruction remains stilled of all movement like a stone.

“The idea is to capture an epic catastrophic movement,” Mercier explains. “It could be mud flow, or landfill—something in between movement and stillness that looks like it just happened, like a visual seen on the news or a fossil from an archaeological site.”

For Mercier, sand is both a poetic and political material. The popular view of sand is one of childhood memories of sandcastles and beach holidays. Yet Mercier shows us that sand has a darker side—one that speaks to ownership and privilege. He points out that a metropolis like Dubai, despite its proximity to the desert, must import sand from Polynesia to create the huge amounts of building materials needed for its expanding cityscape. “One landscape is destroyed to create another,” Mercier says. “This idea of constant transformation and mutation is important in my work.” For MIRRORSCAPE, the sand has been collected from the north of Tasmania and at the project’s end, will be returned there. “It’s a bright, white sand from the mountains. It’s a good sand to sculpt because the grain is thin and there is still a lot of clay in it.”

The history of the landscape is important to note in a colonised country like Australia. Mona itself is built into solid sand-stone and sits on a peninsula surrounded by the estuaries of the Derwent River (Timtumili minanya). Ancient shell middens are tucked into its shores, built up over hundreds of years by the site’s traditional owners, the Mouheneenner people. The destruction and re-construction of land connects deeply to Tasmania/Lutruwita and Australia where land has been stolen from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and never ceded. This history feeds into Mercier’s underlying query—how and why does a landscape change over time? Ashe puts it, “What we work with is behind the scenes of sand. It’s dark, political and economical and nothing to do with childhood, beaches or vacations.”

MIRRORSCAPE marks the first time Mercier has presented a single sand sculpture. Usually working with multiple pieces in exhibitions that often include a performance element, here his work will remain behind glass to preserve its longevity. “Sand interests me as it has contradiction,” he says. “It’s something you cannot really reach, cannot grab, but it’s also something that’s super solid.” To begin each sculpture, Mercier and his team mechanically compact large amounts of sand and water into concrete-like blocks. The tools used to craft the details are often everyday objects, serendipitously found, like forks or odd pieces of plastic. “I love these imaginary tools as they create something so specific to the finished piece.” Textures and shapes are informed by the chaotic forms of landfill and natural structures worn away by erosion.

Mercier has previously worked with waste destined for recycling, antique dinnerware, stone, household appliances and classical sculptures. An aura of spectacle and theatricality is always evident (Mercier is also a stage director) and his work is visually composed to embody a sense of grandeur. This was recently evident in Skinless (2024), where three performers interacted with an apocalyptic landscape entirely constructed from stacks of compressed cardboard and aluminium waste.

In other projects, objects like fossilised trees, architectural ruins and furniture have also been rendered in sand, always connecting back to the place they are exhibited. “When a sculpture is made, there is an expectation you can install, deinstall, sell, buy, keep all this. With a sand work like MIRRORSCAPE, you cannot move that sculpture. It will be visible here only in this museum at this time and it’s always made on site. It will never be somewhere else. We try to create a specific story regarding the place where we are showing it.”

Sharing the ground level of Mona’s Round House with Mercier’s MIRRORSCAPE is Sternenfall / Shevirath ha Kelim (Falling Stars / The Breaking of the Vessels) (2007), Anselm Kiefer’s towering configuration of books made from slowly disintegrating leadand glass. Also in proximity is Hiroshima in Tasmania, The Archive of the Future (2010) by Masao Okabe and Chihiro Minato, where a line of rectangular stones has been transplanted from the Ujina railway station in Hiroshima, Japan (destroyed by the atomic bomb in 1945) to Mona.

Each installation asks the viewer to consider how we process and retain trauma on a global and personal level. The presence of Mercier’s temporary sand structures in this space completes a trifecta of work unearthing elements of a shifting landscape of history, objects and knowledge.

Théo Mercier: MIRRORSCAPE

Museum of Old and New Art (Hobart/Nipaluna)

On now—16 February 2026

This article was originally published in the March/April 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.