Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

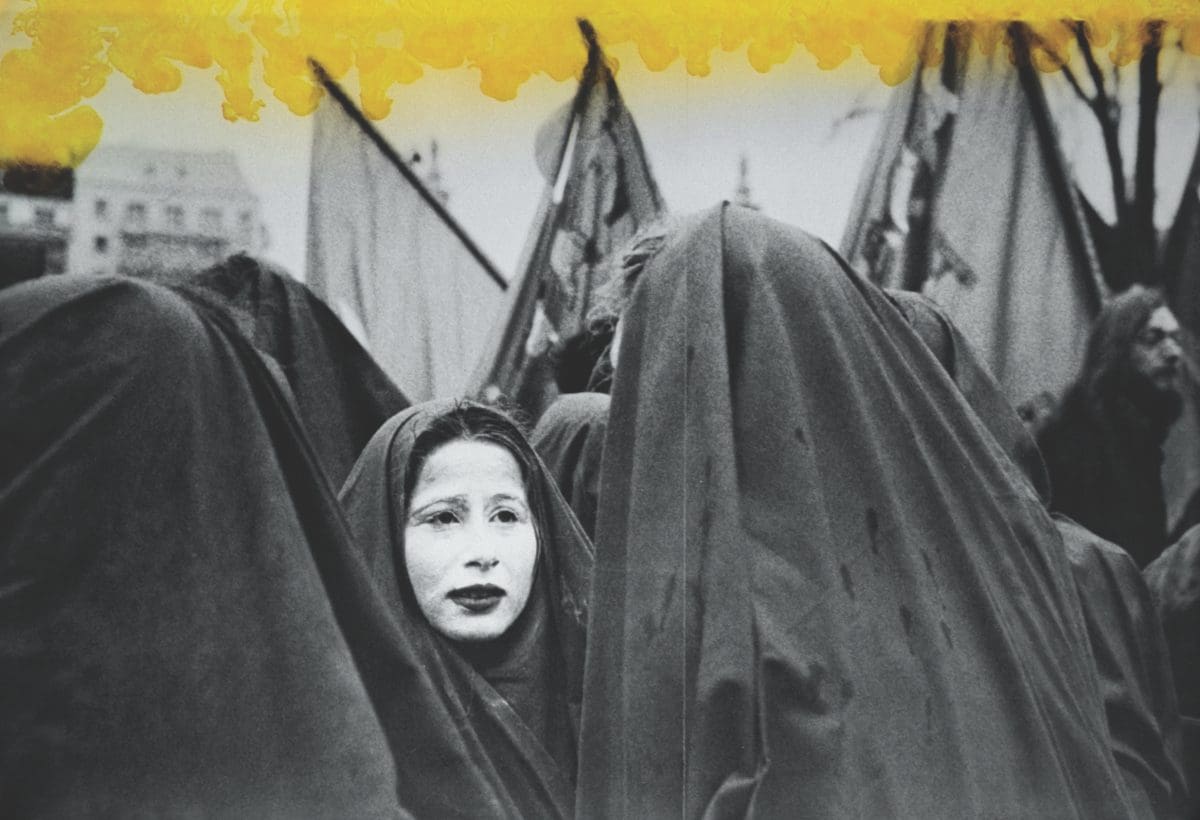

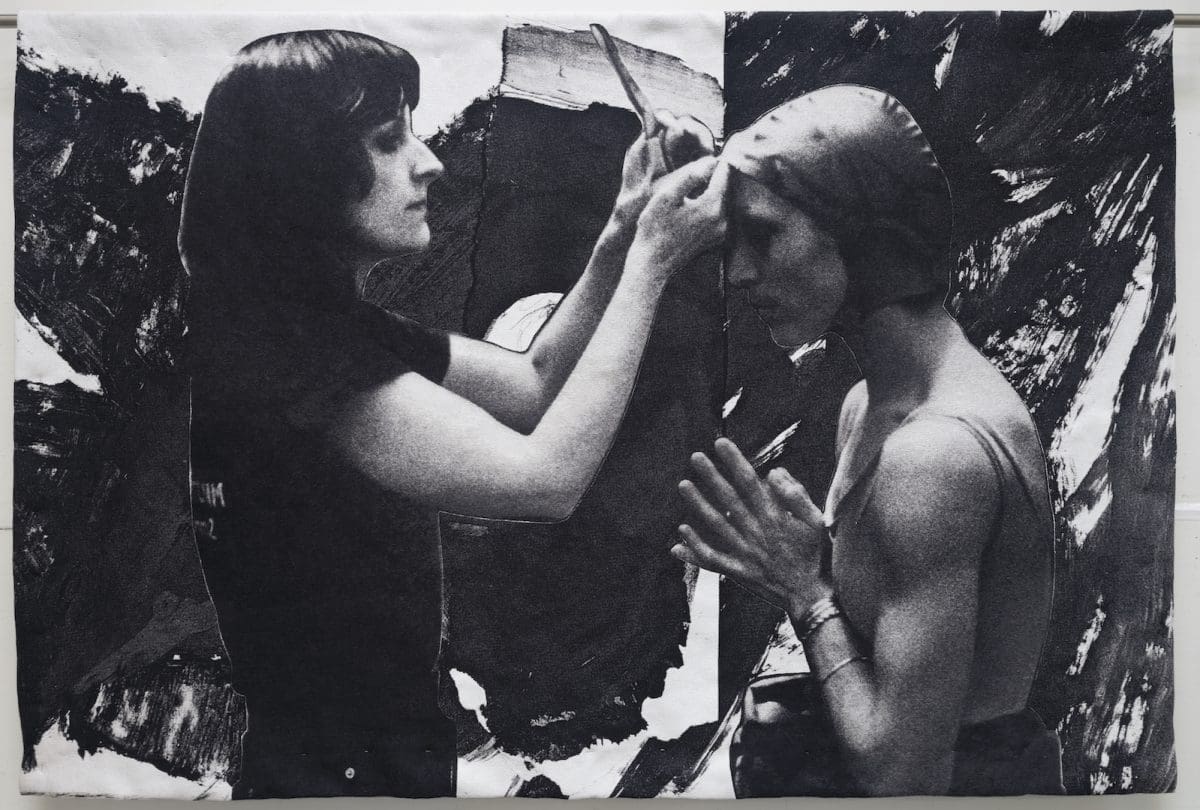

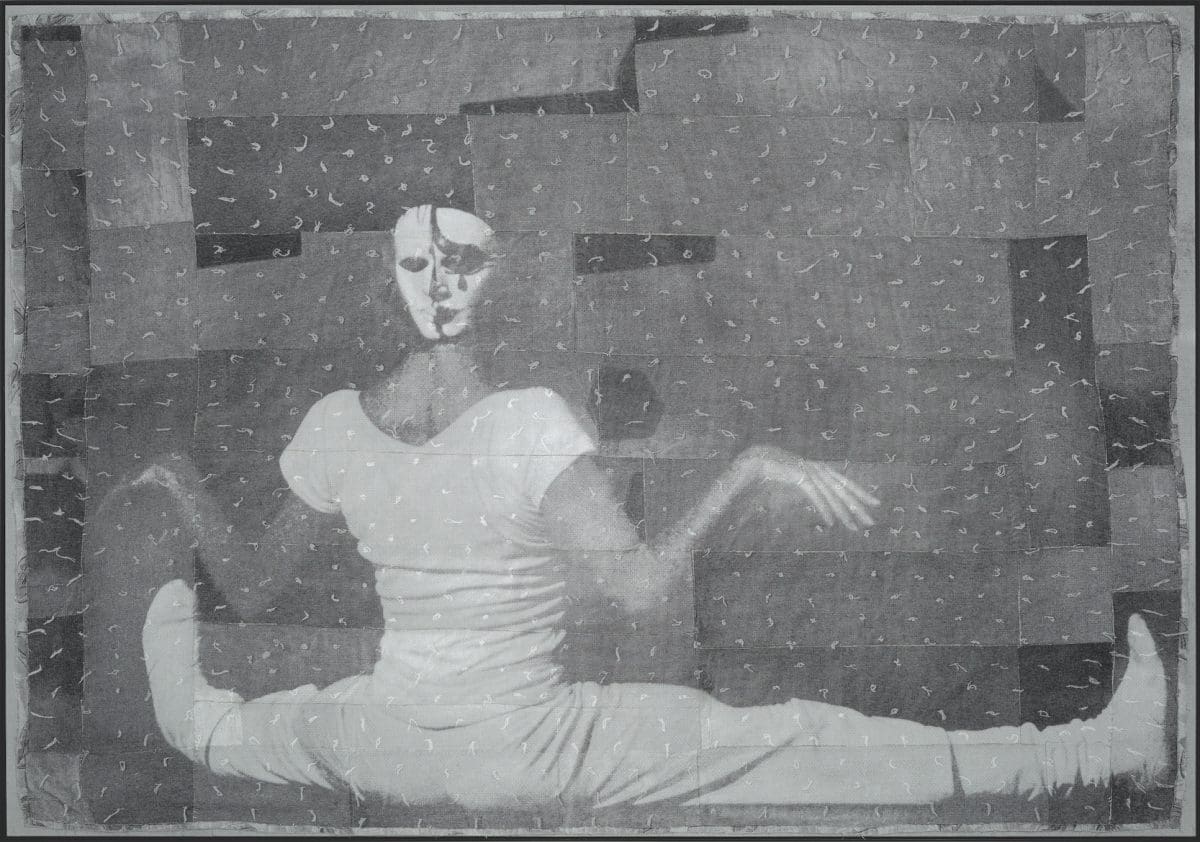

Highly stylised European-centric and Japanese theatre have long influenced Ballarat-born artist David Noonan’s film, collage and sculpture making, in which his figures are often presented in liminal states, positioned somewhere between lacking self-consciousness and performing for display.

Despite basing himself since 2005 in London, one of the great theatre cities in the world, Noonan rarely sees contemporary stage productions, instead naming long by gone productions of expat Melbourne opera director Barrie Kosky, as well as opera based on American composer Philip Glass’s music, as formative artistic provocations.

Moving between representation and abstraction, Noonan’s art relies more on his memories of such theatre artists’ mise-en-scéne: “I don’t know whether the [avant-garde] theatre I’m interested in is really available any more,” he says during a short visit to Australia to unveil his latest exhibition at TarraWarra Museum of Art. “I’m not that interested in conventional theatre; it’s more the aesthetics of it. In the 1960s and 70s, there was a period of amazing experimentation, particularly in set design. The imagery left over from such theatre has a science fiction quality, constructing a world that exists outside our own: props and a DIY construction environment.”

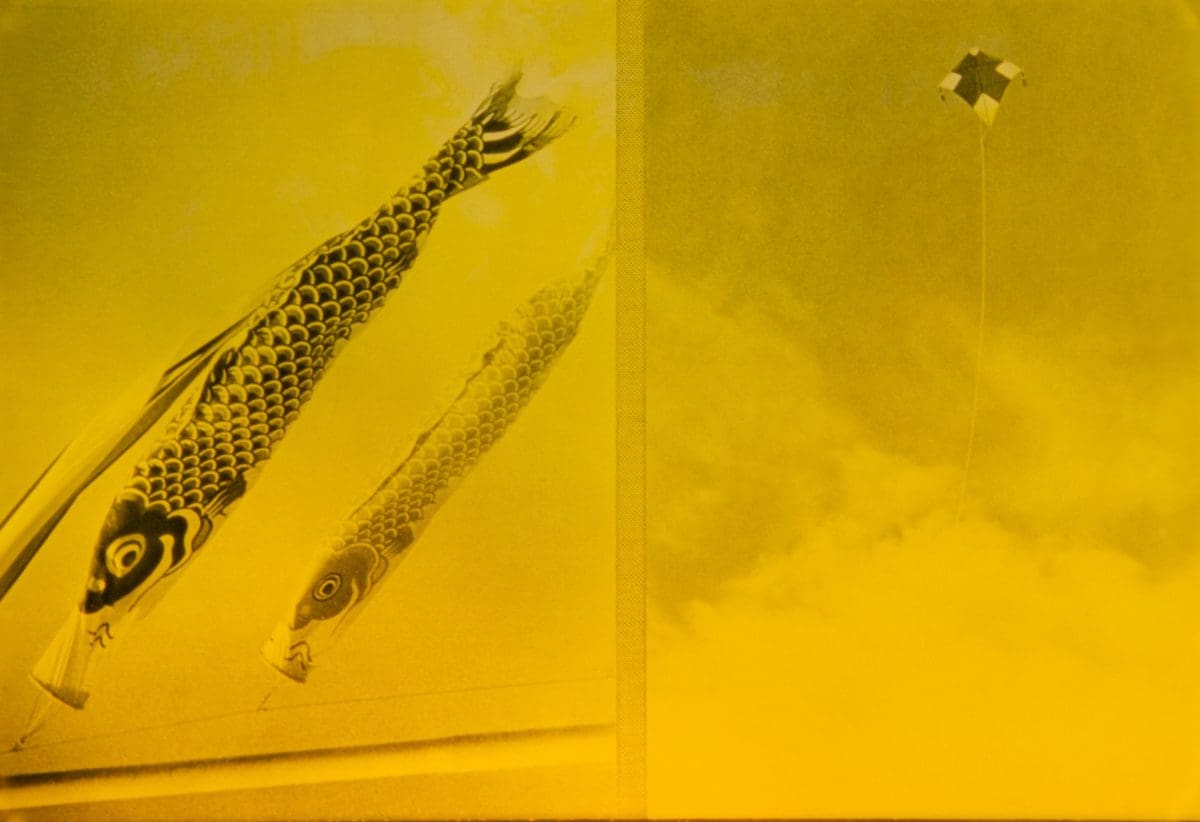

Noonan went through a period of being interested in Japanese stage traditions of butoh and noh, which combine theatre and dance techniques. The title of his new show, Only when it’s cloudless, is borrowed from the writings of the 14th century Japanese Buddhist monk Yoshida Kenko; its inherent suggestion is to be mindful of the present, but also to reflect upon the less obvious. The show includes a new 16mm film, scored by musician Warren Ellis—a childhood friend from his Ballarat days—which utilises some of Noonan’s accumulated imagery from Eastern and Western theatrical traditions as well as fragments from popular subcultures and social media sites.

Only when it’s cloudless includes a major new sculptural installation that looks like a stage set. There are new tapestries, as well as tapestries previously seen at the 2020 Adelaide Biennial, plus collages on linen, some new and some from 2012 not previously seen in Australia. Together, the components of the exhibition were conceived as a unified installation. “The aesthetic of the show is very tight: nothing was put in that didn’t fit,” he explains. “It’s very particular, in terms of the palette.”

Born in Ballarat in 1969, Noonan held his first exhibition in his student apartment in1987, featuring paintings from his second year of art school at Ballarat University College. He worked part-time at local cafe and record store L’espresso, and the northern hemisphere music he liked was a siren call: Sex Pistols, The Damned, David Bowie, Lou Reed, Siouxsie Sioux, The Slits, Steve Strange, Adam and the Ants. “In Ballarat, if you were into any kind of alternative lifestyle, you just did not fit in,” he recalls. “It was so rough and tough—and myself and the friends I made, we were just complete outsiders, on the peripheries.”

“We had to make our own culture in Ballarat, which is what we did. I wasn’t a musician, I was one of the only visual artists in that group, but there were a lot of bands. There was a lot of dressing up and acting out stuff, and we made our own films. We made a lot out of being in a pretty grim situation in some ways.”

Noonan initially moved to London in 1995 on a two-year visa, around the time the young British artists’ movement was taking flight. He moved back to London a decade later, after living in New York and doing various residencies. “When I went to London in the 90s, I did it tough, it was hard. No one had any money. It was a very different London to what it is now, but I found it really exciting. I worked in Soho at a restaurant and at the Tate Gallery bookshop, so I met a lot of artists there.

“The art I was into was coming over from the [European] continent and being shown, mostly from Germany and Italy, in smaller galleries. That really influenced my own practice; I was not really interested in the young British artists at all: it was just too mainstream.”

Noonan says the 16mm film format he has now returned to for the first time since the 1990s is intrinsically beautiful. “I could have shot it on video quite easily. It’s a clockwork camera, an old Bolex from 1956, and you wind it up. It runs for 30 seconds, and then that’s it; you have to rewind it.”

Beauty also lies in Noonan using a difficult process to transform and manipulate space, thereby enabling his audiences to easily project personal meditations onto his images. “I’m more interested in creating a set of conditions to experience an artwork,” he says, “rather than the viewer having to unpack it in a certain way.”

Only when it’s cloudless

David Noonan

TarraWarra Museum of Art

Until 10 July

This article was originally published in the May/June 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.