Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

HOUSE PARTY completed interior view featuring LOOP 6 by Dave Court, digital rendering.

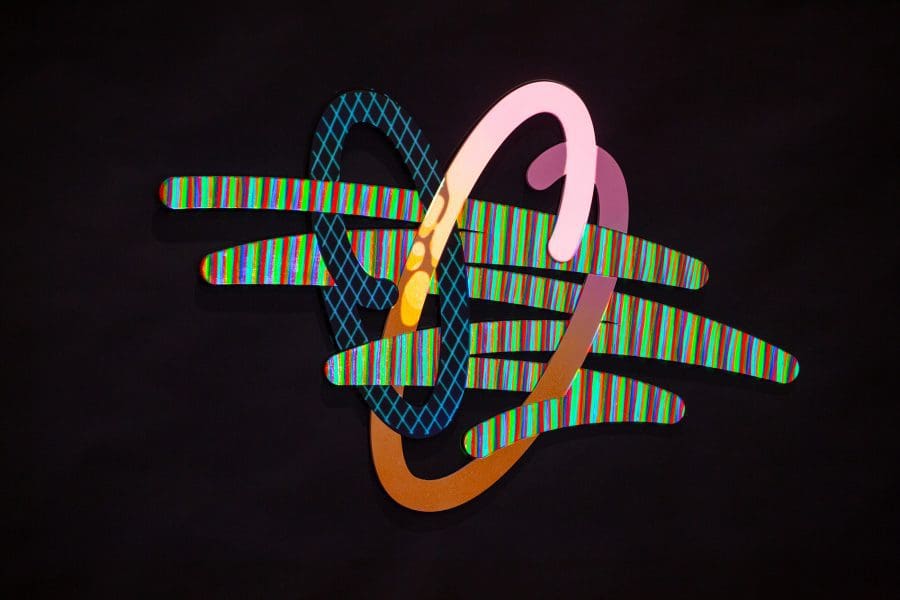

HOUSE PARTY featuring Loop Gesture 5 by Dave Court, acrylic paint and spray paint on laser cut mdf.

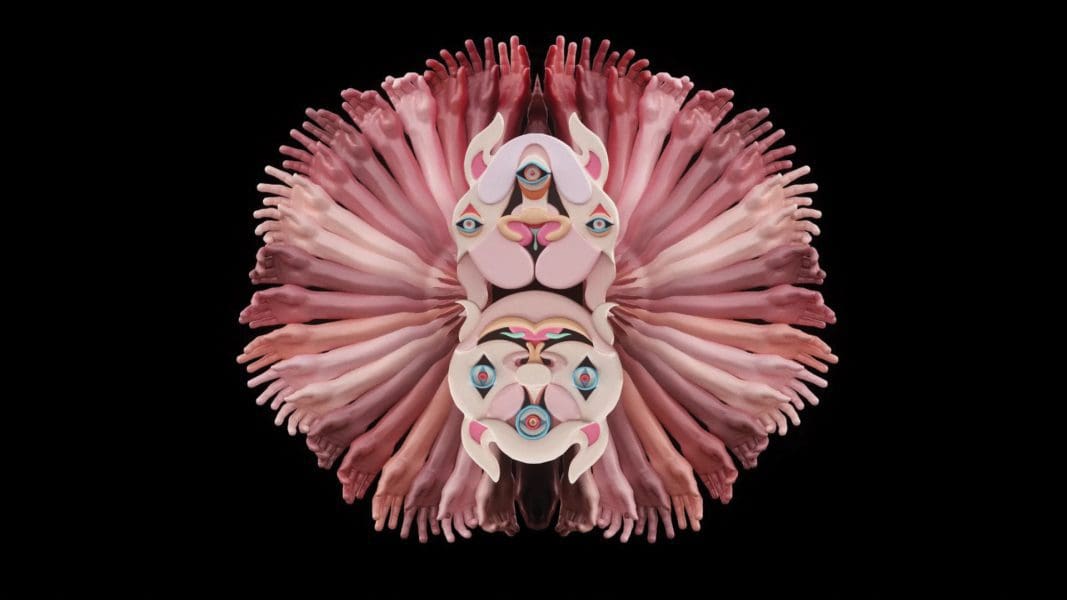

Jess Johnson is selling NFTs on platforms such as Foundation, LGND, hicetnunc200, and through TRANSFER Gallery. Jess Johnson + Simon Ward, WEBWURLD, 2017, sound by Andrew Clarke, single-channel HD digital video with audio, 16:9, 2 minutes, 8 seconds.

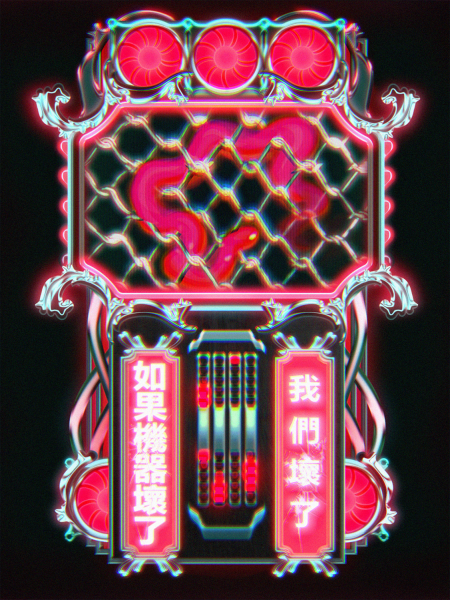

Rel Pham, The Machine (2021), mp4, 2250 pixels x 1750 pixels, 24 frames per second.

Catrin Welz-Stein, Running with wolves.

Early one morning, in March 2021, Melbourne-based artist Rel Pham stared at his computer in disbelief. His animated artwork was at the centre of an online bidding war worth thousands of dollars: more than he’d ever sold a painting for, let alone a video file. The artwork, titled In their mutual interest, depicts a snail perched atop a white rose in the grasp of a monstrous hand. White petals drift across the tableau, which glints occasionally with anime-style starbursts.

The website where this online auction took place is called Foundation. On this platform, In their mutual interest is visible for all to see; there’s no compression, no pixelation, no animation frames. I was even able to download the artwork in full resolution to my own computer, without paying a cent.

But the winning bidder did not pay the equivalent of $4000 to just download the video file. What Pham had really sold was a ‘non-fungible token’, or NFT. Since March 2021, when Christie’s auction house famously facilitated the $US70 million sale of an NFT by digital artist Beeple, the art world has been forced to reckon with what NFTs will mean for the industry. But what exactly are NFTs, and why is there so much interest in them?

The languages of blockchain, crypto and NFTs are gratuitously opaque. All too often complex words become a decoy for more important discussions about NFTs in art, so it’s worth demystifying certain terms and assumptions.

A recent article in The New Yorker described NFTs as the following: “Broadly speaking, N.F.T.s are a tool for providing proof of ownership of a digital asset. Using the same blockchain technology as cryptocurrencies like bitcoin—strings of data made permanent and unalterable by a decentralised computer network—N.F.T.s can be attached to anything from an MP3 to a single JPEG image, a tweet, or a video clip of a basketball game.”

Taking this back a few steps: everything on the internet is stored on a server, including artworks, music, and videos—and blockchains are one of many options for how that information is stored. It’s helpful to think of blockchains like virtual nations. One of these ‘nations’ is called Ethereum, and its currency is Ether. Ether is a fungible token. Like the value of a ten-dollar bank note, one Ether always has the same value as any other Ether. NFTs are different: their value can shift, like the auction price of a particular painting, or a particular edition of a print (and they don’t always represent artworks: they can represent anything within a blockchain that we’d want to assign an unfixed value to).

In art, an NFT can act as a certificate of authenticity, a mark of scarcity, or a record of ownership and value—and similar systems existed long before the internet. For example, it’s useful to consider how NFTs mirror the Renaissance-born arts patronage system that we still use today. In fine art terms, the NFT is the plaque at the foot of the statue informing the public: ‘on loan from the Guggenheim Estate’. It’s the database entry stored by Sotheby’s auction house that tells us how much Munch’s The Scream is worth. These are not what we would usually consider the art object. But the value of having your name on that plaque, or alongside that dollar value, is indivisible from the artwork. When you buy an NFT, you’re not merely buying an artwork, but the status or record of owning that edition of the artwork, too.

Foundation—the digital, concept-driven marketplace where Pham’s NFTs are listed for auction—is marketed as a curated, artist-centric platform. This business creates the NFTs that represent each artwork, and then facilitates the auction process. The artists selling via Foundation generally demonstrate a strong vaporwave aesthetic—brightly coloured creations soaked with early-internet nostalgia— across works that are 3D-rendered, pop-surrealist, animated and Instagram-native.

Digital media expert Scott McQuire likens artists’ adoption of NFTs to the system of limited editions embraced by 20th century printmaking and photographic artists. Both use the tactic of artificial scarcity in response to a medium of proliferation. “There’s a lot of interest in things being free on the internet,” McQuire says. “But if you’re the creator… how are you going to deal with financial sustainability?” In other words, how are digital artists going to ensure they’re paid for their artwork?

Since launching in January this year, Foundation alone has created more than 10,000 NFTs for digital artists looking to ride the crypto-wave, and it’s just one of the many platforms providing this service. On Foundation, Pham’s NFTs appear alongside many other Australian and New Zealand artists and designers, including Jess Johnson, Serwah Attafuah, James Jirat Patradoon and David Porte Beckefeld.

In making the digital more tactile for audiences, Australia’s first physical NFT art gallery, the Museum of Art and Philosophy (MAP), opened in Hobart in June; and artist Dave Court is selling an NFT alongside physical artworks at his solo exhibition HOUSE PARTY at Praxis Artspace in Adelaide. Artist Kieren Seymour similarly sold his works with an accompanying NFT during his March solo show at Neon Parc in Melbourne.

Beneath the choice to move into NFT sales is the promise of economic and creative freedom. Serwah Attafuah, a Western Sydney-based 3D artist, started making NFTs with Foundation in 2020. On Foundation’s blog, she wrote: “I think that releasing more NFTs could be a really good way to move into being an artist as my main thing. I want to get to a place where I can rely less on clients and freelance work, which I feel is suffocating me in a way.”

With enormous funding cuts to the Australian arts sector and a financially frugal client base in the wake of Covid-19, and the possibilities of the new realm of digital art and NFTs, it’s no surprise that artists are seeking these new, potentially lucrative income streams. At the same time, some are questioning this new system.

Anita Archer—a Melbourne-based art market expert and collection adviser—isn’t sure NFTs can fully offer the solutions artists are looking for. “People who are deeply passionate in this field talk about how it’s this utopia that’s going to be wonderfully liberating and . . . the best thing that could happen to artists,” she says. “But it’s certainly not what we’re seeing at the moment.” Although she thinks NFTs might one day have a legitimate place in the art market, Archer is concerned that problems with gatekeeping, authenticity and exploitation of artists are being reproduced in the NFT space.

Assuming you can get past the impenetrable terminology and the mystification of crypto-currency (and the environmental concerns of high carbon emissions associated with creating and trading NFTs), there are many more barriers to entering NFT art trading. Some NFT marketplaces are deliberately exclusive: Foundation is invite-only, or you can buy your way in by purchasing an NFT from one of the platform’s existing artists. To create or purchase NFTs, artists and collectors need to buy some of that virtual currency, Ether. And then there’s ‘gas’, a fee for any blockchain transaction: this includes things like currency conversion, creating an NFT, placing bids, and transferring NFTs from one owner to another.

Pham sees these costs as a business expense— like paintbrushes and canvas, or gallery commissions and hire fees—but he’s aware there’s a lot of profit being made from artists’ buy-in to platforms such as Foundation. “The narrative that gets pushed a lot is everyone has an equal chance, but I don’t think the reality is that,” he says. “As much as the platform’s meant to be democratic, there’s a material issue to it, in terms of who has access to that capital and who can start off.”

Echoing similar concerns, Los Angeles-based new media and video game artist Cassie McQuater wrote in a tweet about NFTs: “Cryptocurrency may be disrupting some parts of the art ecosystem but it’s definitely not threatening the underpinnings of capitalism itself or even the perverse influence of the super-rich on our artistic practices.”

The winning bidder of Pham’s In their mutual interest NFT is a 49-year-old American man named Chris Dixon, a venture capitalist involved in everything ‘tech disruption’, from virtual reality to social media to biohacking to crypto. Last year, he led venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz’s $23 million investment in the NFT marketplace OpenSea. In the mainstream NFT space, invested patrons like this are common: the two main bidders in the infamous Beeple auction were Vignesh Sundaresan and Justin Sun, who are both heavily invested in crypto platforms themselves.

As Archer points out, if the NFT marketplace is being buoyed by such ‘invested’ patrons, it wouldn’t be a first in the art world. “Let’s not think that any of the other [art] markets haven’t been manufactured,” she says. “It’s no different if we think about the market for French Impressionists, who did a similar thing.” Archer is referring to the 1800s French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who would sometimes bid on his own artists’ paintings at auction to inflate the price and grab the interest of collectors. Durand-Ruel’s actions raised the value of the artists he represented, such as Monet and Manet, which in turn brought prestige to his own gallery. He was creating ‘value’ in art, and—for better or worse, depending on your viewpoint—is now celebrated as the father of French Impressionism.

By extending elements of this ‘value creating’ system into an online space, the NFT market carries both the merits and problematic politics of that same economy. The NFT market was not created by artists, although, optimistically, many artist-led platforms have emerged in recent months. Johnson and Attafuah have started creating NFTs outside of Foundation, on platforms such as LGND, hicetnunc200, and as part of TRANSFER Gallery’s Pieces of Me exhibition. These alternatives diversify the digital art space, advocating for better conditions for artists, and offering a positive glimpse into the future of NFTs in art.

The hype of NFTs has undeniably brought digital art to the public psyche like never before. Antipodean artists have been engaging with the digital medium for decades, yet nuanced discourse about the ethics of this industry is too often sidelined by debate over the legitimacy of digital art and ‘low brow’ culture in general. This may be a symptom of Australia’s technophobia, and certainly seems like a byproduct of neglected investment in both art or technology. But if the Christie’s multi-million-dollar NFT sale wasn’t evidence of a coming-of-age for this genre, then perhaps the verification comes instead from a growing interest in the politics, economic future, and ecosystem of the digital arts.

HOUSE PARTY

Dave Court

Praxis Artspace

24 June—23 July

PERCEPTION — INTERPRETATION OR FACT?

Museum of Art & Philosophy

8 July—31 August

Pieces of Me

TRANSFER Gallery

piecesofme.online

Foundation

foundation.app

LGND

lgnd.art

This article was originally published in the July/August 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.