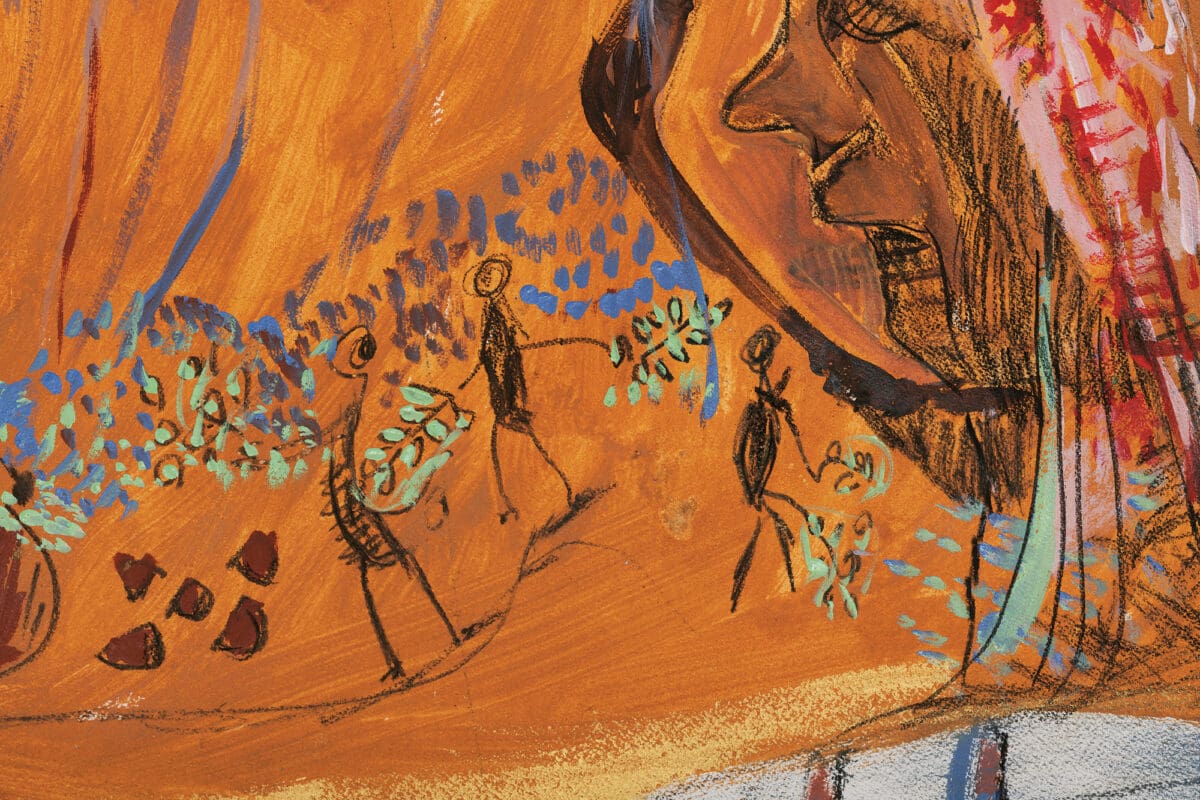

The first thing you notice is the scale. Nine metres of paper stretch the length of the gallery wall like a riverbed of memory. Painted in acrylic, charcoal and oil stick, the monumental work—titled My Story (2024)—unfurls as both map and memoir. A vast, undulating chronology of red dirt, ghost gums and saltbush, it’s the largest work ever created by Yindjibarndi Elder and artist Wendy Hubert.

“I born in bush,” Hubert told exhibition curator Zali Morgan in December 2024. “I grew up in the station. My mum died when I was a little girl. That’s when the atomic bomb blew.” These words feel stitched into the painting’s very fabric, not as illustrations of trauma, but as a form of sovereign storytelling.

My Story is a sweeping visual narrative, threading together memories and terrain from Hubert’s lifetime. At Red Hill Station, sheep graze near homesteads as the phrase “no wages” marks the legacy of unpaid Aboriginal labour. A mushroom cloud rises from a

camp, referencing British nuclear testing, while the words “The Queen is coming” evoke Queen Elizabeth II’s 1963 visit to Western Australia. Elsewhere, eucalypts, waterholes and dusty roads root the work in Country. Hubert moves between memory and witness, drawing quiet strength from the land as she honours its stories and her place within them.

Hubert, a member of the Juluwarlu Art Group collective who is now in her seventies, began painting in earnest after the death of her husband in 1989. “It’s called mourning,” she told Morgan in the same conversation. “You gotta do something with your life.”

For decades Hubert, who will also feature in the 25th Biennale of Sydney, worked in community health; now, she paints to preserve memory , to honour Country and live in joy. “I want to live happy in my life. Doing art is a perfect thing.”

My Story was commissioned by Fremantle Arts Centre as part of It’s Always Been Always, an exhibition that centres Blak women as custodians, connectors and cultural leaders. Curated by Morgan, a Whadjuk, Ballardong and Wilman Noongar woman, the show brings together six Aboriginal women artists from across the continent. Working across painting, video, installation and text, each reflects on the matriarchal lineages that carry—and continue—Culture. The exhibition proposes a kind of chorus: distinct in voice, unified in strength.

In a quiet gallery next door, a circle of soft light shimmers against a wall. This is A beam of light (2025) by Wiradjuri poet and artist Jazz Money, a tender video installation capturing the shadows of the artist and their newborn child cast onto a sheet in the late afternoon. The soundtrack is a lullaby of sorts: birdsong, baby murmurs, and the voice of Money’s partner singing them to sleep.

“Our daughter’s name means ‘a beam of light’ in Wiradjuri,” Money says. “It felt like a way to mark this moment of transition. Not just for her, but for me.” Becoming a parent, they reflect, reshaped their outlook in unexpected ways. “I always thought I was a bit pessimistic… but you can’t bring a child into the world unless you believe it can be worthy of them.”

The work is intimate and unadorned—no poetic text, no ornate production. Just a circle of light and shadow, in which the legacy of 65,000 years of survival and joy seems to pass from hand to hand. “There’s trauma, yes,” they say. “But there’s also abundance. There’s majesty. I want my daughter to feel proud of her heritage, not ashamed.”

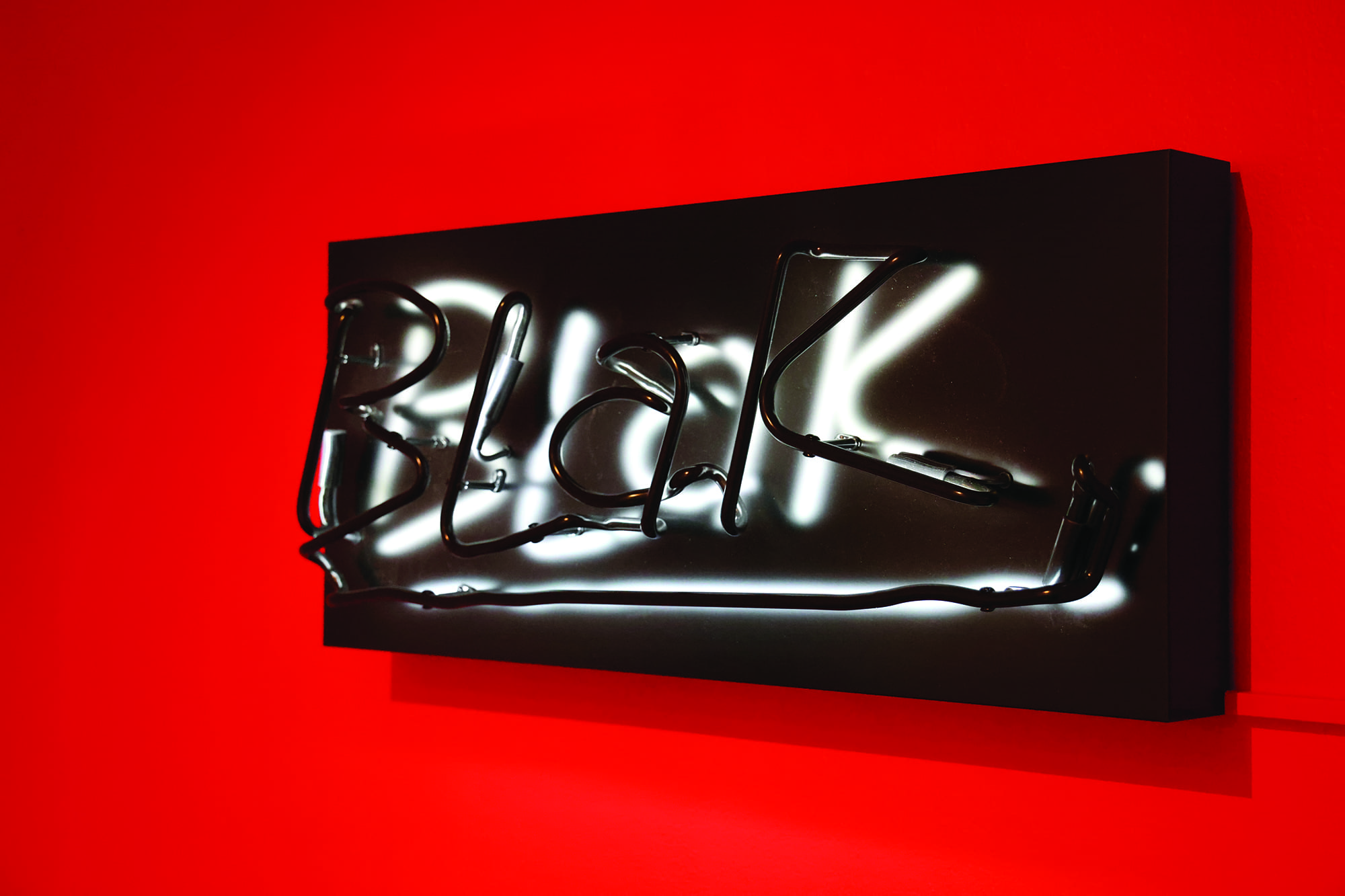

Amanda Bell’s works explore the weight of language and the politics of visibility. Her work

Your Blood, My Blood, Our Blood (2023) spells BLAK in white neon tubing against a vivid red wall—a bold assertion of identity and cultural pride. Nearby, a sprawling text installation titled Ngobooloonginy (Bleeding) (2025) stretches across the gallery in handwritten red script, invoking rage, kinship and connection.

In Alidja Maara (2025), Yabini Kickett presents a layered portrait of matriarchal strength and

intergenerational knowledge within Noongar culture. Set against a soft, radiating wash of solar dye, pastel and watercolour, the image depicts a pair of outstretched arms offering upwards—a gesture of protection, guidance and giving.

Harriette Bryant’s assemblage of wall-mounted antique objects, including silver trays, suitcases and teapots, are painted with scenes of nuclear testing and frontier violence. By transforming colonial relics into vessels of truth-telling, Bryant reclaims power from the tools of propriety.

For Hubert, that power comes through remembering. Alongside My Story, she exhibits a suite of smaller works: Afghan palms from her childhood Country, gum trees dappled in shade, a 1972 dining room where she first learnt “to work and eat properly.” Each painting is a kind of ceremony—a reckoning with time, and a refusal to be forgotten.

“I know my Ngurra,” she told Morgan. “I know its Laws. I’m old now, but strong in my thinking and my life.”

In this way, It’s Always Been Always is less an exhibition than a collective invocation. It doesn’t just honour matriarchs—it listens to them. It lets them speak in the voices they choose: through lullaby, through landscape, through laughter, through line. Rather than positioning these stories as discovery, the show reminds us they have always been here—quiet, powerful and insistent in their presence.

It’s Always Been Always

Fremantle Arts Centre

(Fremantle/Walyalup WA)

Until 3 August 2025

This article was originally published in the July/August 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.