New Zealand-born, Melbourne-based artist Ronnie van Hout has made a name for himself with works that are perplexing, outlandish and disruptive. Take for example Quasi, a surrealmonument to the artist’s hand, installed on the edge of Christchurch Art Gallery’s roof in 2016. As in many of his works, van Hout’s likeness is present, emerging from the five-metre tall sculpture. With an expression that is as neutral as a passport photo, Quasi stared across the earthquake-scarred southern city. Though initially it seemed like the denizens of Christchurch were in on the joke, the giant hand loomed uncomfortably as time wore on. Amid calls to have it removed, Quasi proved to be far more ambiguous and loaded than a one-liner.

Undeterred by the mixed reaction that van Hout is known to elicit, Bendigo Art Gallery has commissioned a new sculptural work for Melbourne Art Fair in August, and prior to that, the 56-year-old artist will be the first artist to be surveyed at Buxton Contemporary.

Melissa Keys, curator at Buxton Contemporary, explained to Art Guide Australia why van Hout was a contender for this first. “Ronnie’s practice now spans more than three decades and references a remarkably diverse, and consistent range of ideas, themes and concerns.” Those concerns draw on his rural, Catholic childhood – the artist has spoken of his unbelief, his fascination with UFOs and the chicken farm in Aranui where he grew up, shovelling manure, collecting eggs and slaughtering chickens. He has returned to his hometown time and time again in his practice: House and School, 2001, is a model of both his home in Aranui and the Catholic school he attended. In an earlier incursion at the Christchurch Art Gallery, he erected one of his father’s farm sheds in front of the gallery. Although van Hout’s works are unmistakably a product of his personal life and history, Keys says that audiences are drawn in by the universal qualities in the experience of contemporary life, which are “complicated, entertaining, funny, fractious, messy and joyful.”

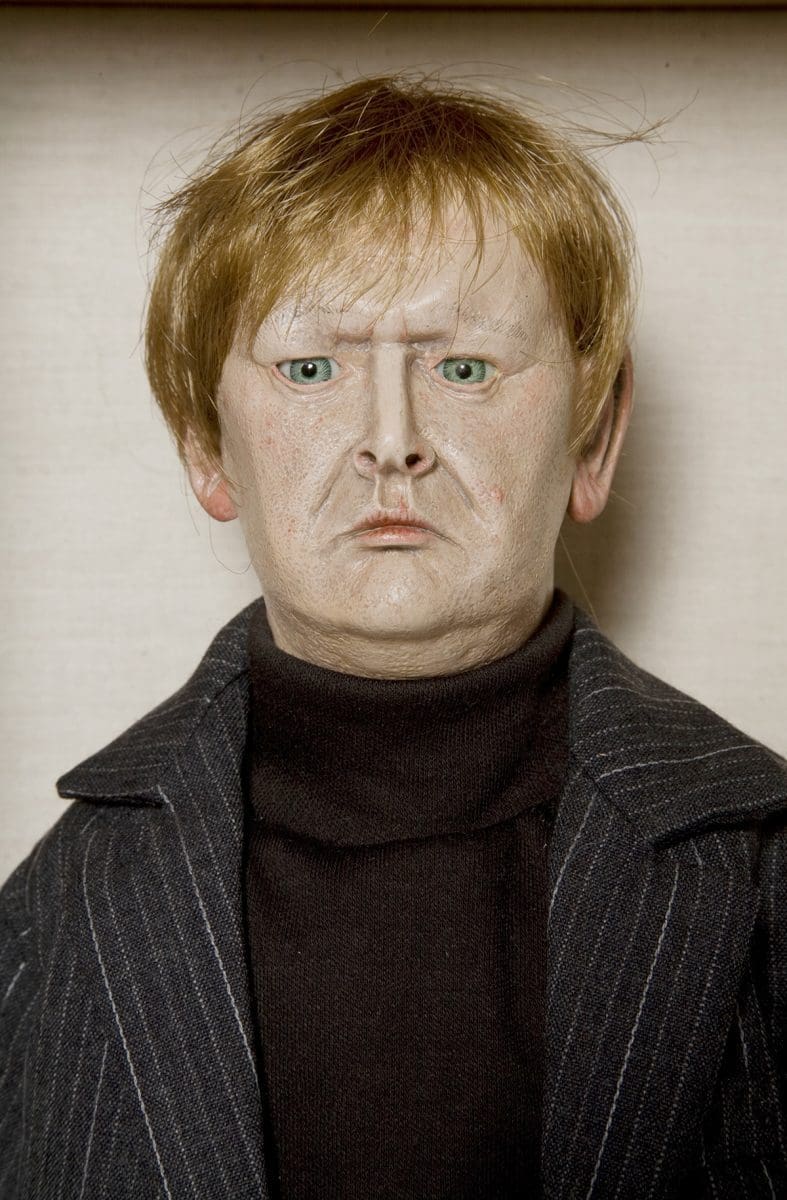

Van Hout’s works tap into contemporary neuroses – you can’t help but whiff both ego and the acceptance of failure in the works that touch on self-portraiture.

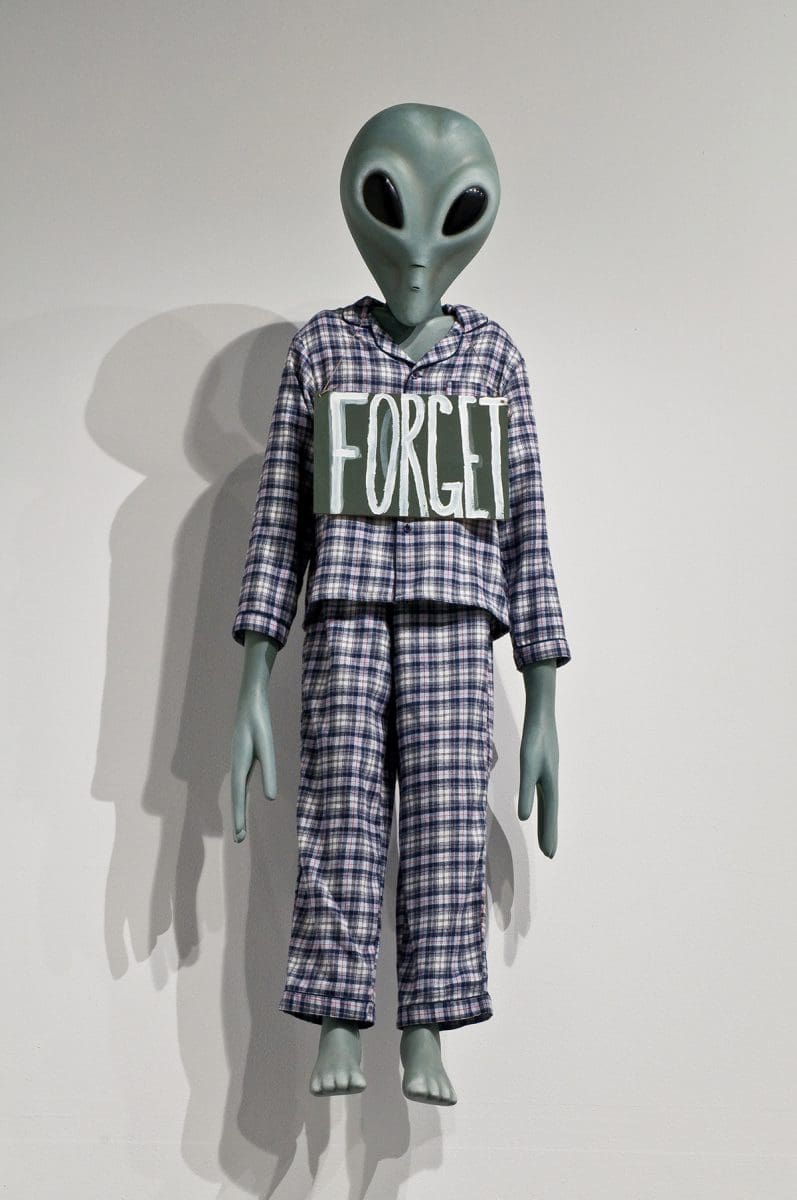

They aren’t pretty. If van Hout is painting the artist as a naked emperor, he isn’t choosing the most flattering shades. The Pointing Figure from 2017, for example, exhibited at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art during The National last year, hid neither its grotesqueness nor its DIY quality with pockmarked skin, Goth black bob and facial folds more often seen on pedigree dogs. And that was one of the tamer figures in the room. To Love and be Loved in Return, positioned in the corner of the room, was more viscerally confronting featuring a string of sausages joining the mouth and presumably, the anus, of two Ronnie-type figures.

There are very few people who can do this and still come off somehow affable. Maybe it’s the childish pyjamas one of the figures is wearing, perhaps it is the title that alludes that anything – even being bound together by processed meat – is better than loneliness. Perhaps it is as Keys says, the artist is more “puzzling, more prosaic, humorous and poignant, more impervious and resistant to definitive readings.” Nietzsche surmised that conceivably the reason why only humans have the ability to laugh is that we alone suffer so deeply that we had to invent laughter. While some may laugh at the awkwardness of van Hout’s works, Keys doesn’t deny that the interiority of the works makes them alarming for some, or else simply absurd. His characters are activated by the life of the people who encounter them. “It’s interesting to see how audiences relate to, identify with, and also disassociate from the characters that inhabit Ronnie’s parallel worlds.”

This idea of suffering is palpable in his Bendigo Gallery commission, titled Surrender. Based on plastic toy soldiers, the two large-scale figures shrink in submission, recalling American school shootings, armed conflicts and the random acts of violence on unarmed civilians that we dread. Van Hout told a New Zealand news website, “I was probably thinking about surrender in all possible ways and particularly as a submissive position in relation to power and the gestures associated with surrendering – the opening of the body and the trust and potential for shame and abuse.”

The opening up of the body is a theme that also drives Bad Fathers, a new body of work that will debut at Buxton Contemporary.

His most ambitious installation to date – Bad Fathers is comprised of a “somewhat chaotic tableau of nude figures that reference a broad range of classical, Renaissance and contemporary sources” and will be accompanied by a new video work.

Keys is reluctant to add more details other than to say that it will be “reasonably epic, confronting and out there.”

No one is watching you, the title of van Hout’s survey show comes with inbuilt irony. Here van Hout is more visible than ever, on rooftops and in public commissions – Surrender will be installed at the Bendigo Art Gallery after its Melbourne Art Fair launch. He might be alluding to the fact that his works remain elusive; van Hout will rarely be drawn on questions of his works’ meaning. Keys says that spending time with his practice in the lead up to the exhibition has opened up “more and more questions, rather than narrowing them down.”

At times, delightfully geeky with an undercurrent of pathos, van Hout’s oeuvre draws on “science fiction, cults and cinema,” with a nod to art history. Keys says that in presenting such a distinctive mix, she hopes to provide a “cinematic sense of unfolding – which is itself important to the artist’s thinking and logic.”

No one is watching you

Ronnie van Hout

Buxton Contemporary

12 July – 21 October

Melbourne Art Fair

Southbank Arts Precinct

2-5 August