Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

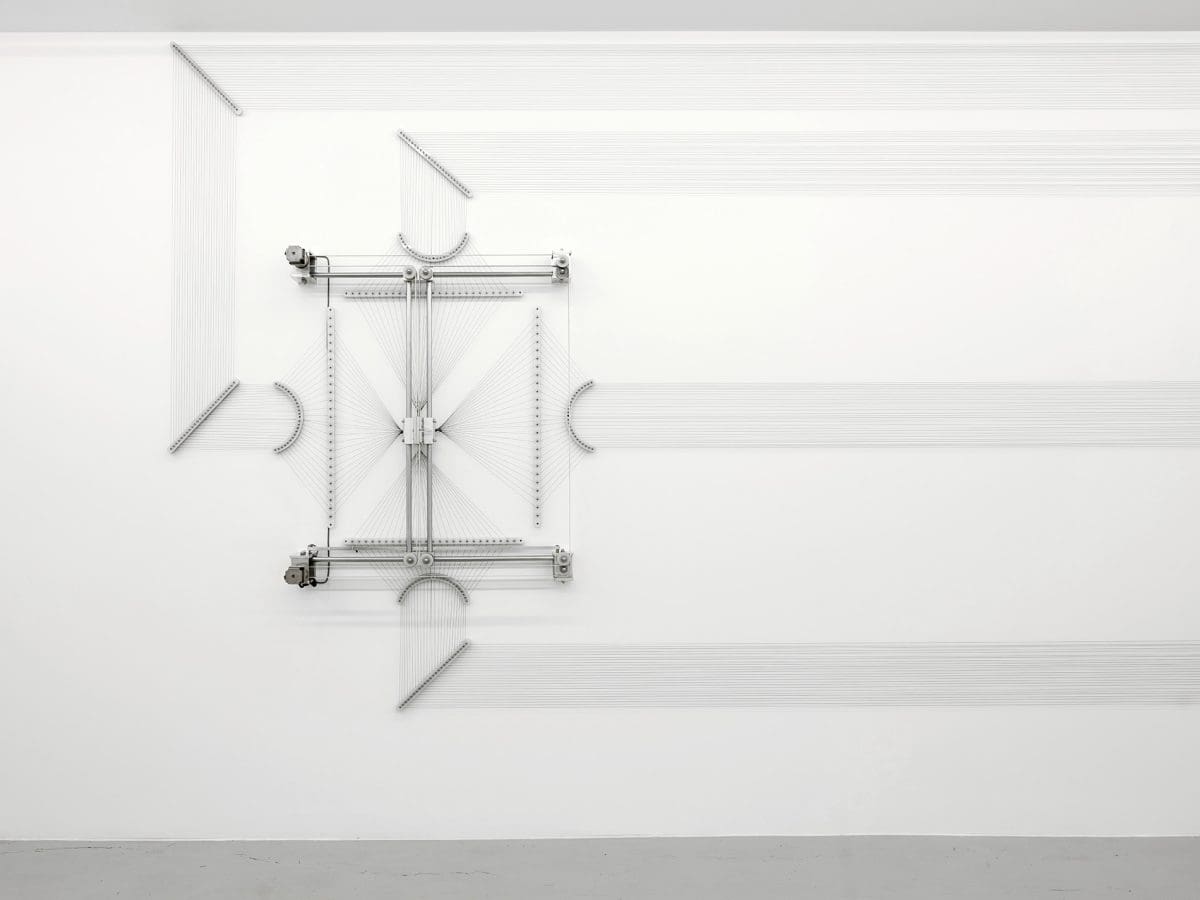

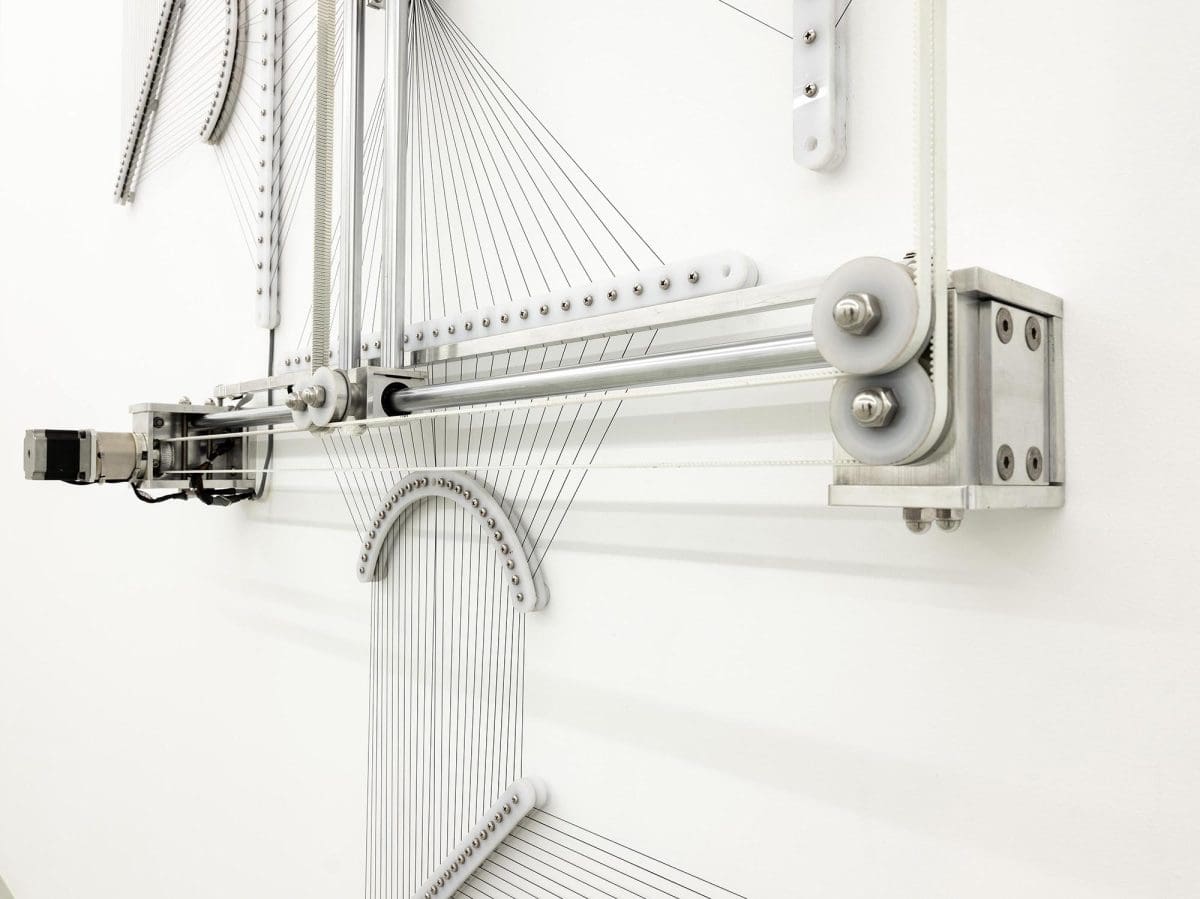

In the last decade, Robert Andrew has become known for his works combining technology and ochre, particularly his palimpsest pieces, which over the course of an exhibition reveal a Yawuru or site-specific, local Aboriginal word. It’s a revealing of language, culture and history, exhibiting everywhere from the National Gallery of Australia to the National Gallery of Victoria. Now Andrew is showing at the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona), responding to lutruwita’s (Tasmania’s) buried history and working with local pakana knowledge holders and speakers of palawa kani: the revived language of Tasmanian Aboriginal people. Andrew talks about this collaboration, discovering his Aboriginal heritage, becoming an artist later in life, and the power dynamics of language.

Tiarney Miekus: Your most well-known works use machinery, ochre, oxides and water to reveal what’s often a Yawuru word on a gallery wall. The first was in 2013 and revealed Mimi, which is “mother’s mother”. It set a trajectory for the next 10 years, but how did that work come about?

Robert Andrew: It definitely has. It started when I had my studio at home, a little room, and the mechanism was built there for my Honours year. I was looking at language and education, particularly my own education, and the layers that have been built up within Australian history—the colonisers’ history that has been covered up. And going back to my own childhood at primary school, there were blackboards and chalk. I wasn’t very good at English subjects, but I started off in my studio with a blackboard and those ideas about writing and rewriting over and over again, which is the idea of palimpsest where you still have that imagery of what lays behind.

So, I had a chalkboard and I was trying to build up layers of chalk and I was using either the water pistol we used to spray the cats when they were doing bad things, or a squirty bottle—and it was spraying onto the blackboard to remove the buildup of a few layers of chalk that I’ve put on there. Even now, all the works have that black chalkboard layer underneath: you don’t see it, it just gives an added depth. And then bringing that idea of the reveal in, and the mechanics of how to do that.

TM: That process of revealing is so central.

RA: A lot of my work revolves around the idea of that slow reveal, of taking back layers, taking back this white facade which represents my own Western education and views—revealing, as I find out more on Indigenous history and my own family.

TM: That intent on revealing coupled with the blackboard is interesting, because you would have used blackboards as a child, and it was only later at the age of 13 you learnt of your Indigenous heritage. It would have been a huge moment.

RA: Yeah, it was. It was my grandmother showing us my great-great-grandmother Mimi—and that’s where I first came across the word. And Mimi’s partner was a Filipino man from Broome. It was a picture of both of them—although not together. But it was seeing Mimi who was from the Broome area, and her family and sisters. And I’d see all my rellies on my mum’s side, when we’d go up to Broome or Darwin in the school holidays, but I was never aware, really. It made sense once I knew we had Aboriginal heritage, where the variations within our family came from.

It was a little difficult, but I was proud to know that I had Aboriginal heritage. Even in those times when there was a lot of racism on TV and news about Aboriginal people. But for me it was hard to locate myself within my Indigeneity. My schooling was about the Aboriginals in the desert, so I didn’t know how to fit into that part of my heritage and where that belonged. I didn’t know the term ‘urban Aboriginal’. It’s obvious in retrospect because all my rellies were living within cities or country towns. But there was a huge, huge distance in time and place between my learnings of Aboriginal people and where I was. It took me a long time to actually locate myself within that.

TM: Art would eventually become central to that, but you attended art school later in life. What were you up to in your twenties and thirties?

RA: I started really late. It was mid-forties I started art. I grew up in Perth and stayed there until I was 21 and then worked with Telstra for seven years and lived up in Broome. My skill set comes from these different places that I’ve worked at along the way, which is really helpful. And when I was in Broome— I really liked living there, but there’s a song about people being young, unintelligent and inebriated. You know, that’s where I was. I didn’t follow up on anything. I visited a few rellies, but it was just about going out and enjoying myself.

From there I came over to Newcastle and was working with my older sister, Deb, for seven years in furniture making and manufacturing. And Deb, from a younger age, has had more of a connection with that side of family and her Indigeneity.

From Newcastle, I came to Brisbane to be with my partner and she introduced me to like-minded peers and mentors in the Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art (CAIA) department at Queensland College of Art. And going back, it was my sister Deb who did a very similar course in Geelong where she learnt about our family, and that sparked my interest into our history, seeing what she got out of it. It was quite confronting for me to hear what she was relaying back to us—not just about our family, but also about other histories. At that time, I was also doing 3D modeling and animation work for architects and engineers, using my computer skills, and then took this opportunity to study more about family and history.

Looking back on it now, it was going from having a wage to no wage. I’m not exactly sure what I was thinking! But I’m glad I was thinking that way.

TM: I’ve seen a few of your palimpsest works and other mechanically based pieces, and I’m always struck by how captivating the works are not just visually, but how the audience becomes so attentive to engaging with the mechanics, the formalism, of the artwork. How do those pieces actually ‘work’?

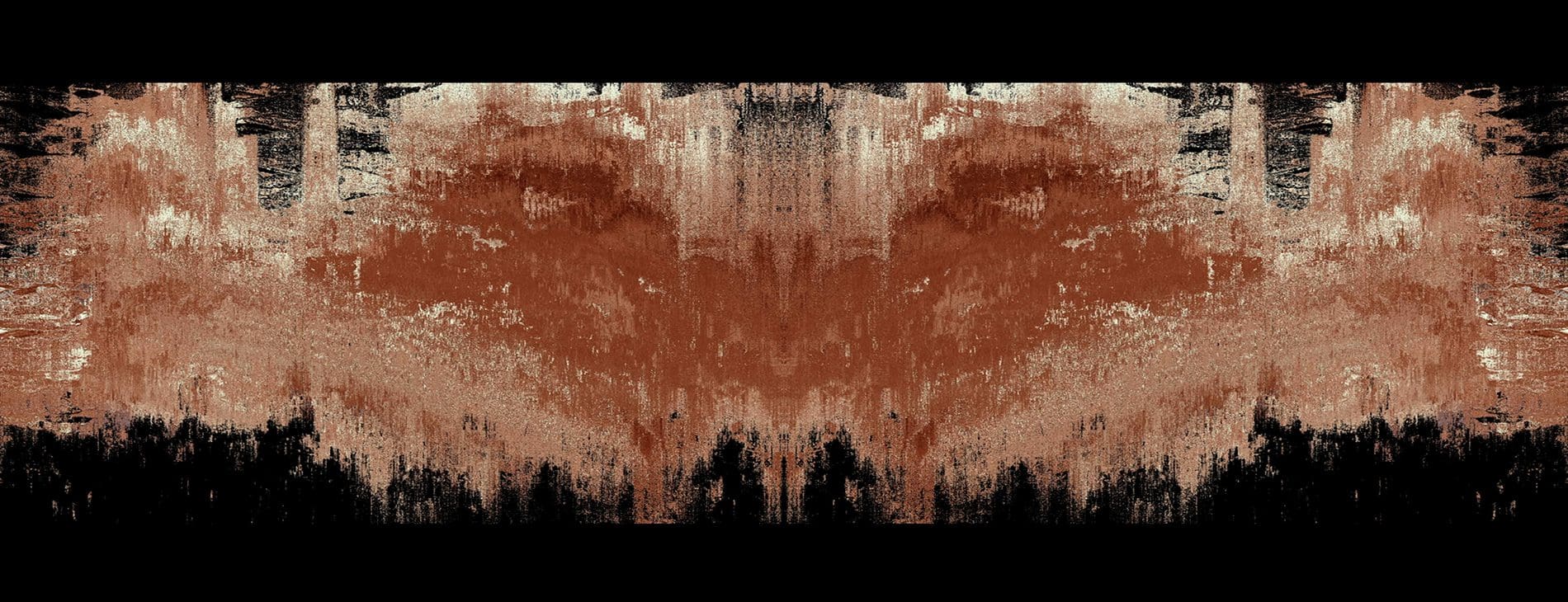

RA: That’s nice to hear the way people engage with the work. It’s that slowing down of time for people, bringing people in. The whole mechanism operates on slow time, over a longer period of time. You’re getting such a small moment, but then you can project that forward: you can see the history of the work and anticipate it moving forward. With the palimpsest works, it’s layers of ochres and oxides built up and then white chalk—but it gets seen as ink going onto the surface, as opposed to the idea of the water spraying and taking little sections of that ochre and white chalk off, and having it bleeding down to reveal what’s behind.

There’s layers and layers in my process of programming, and I put the text on there as the space that doesn’t get eroded. There’s a different program for each day depending on the length of it: if there’s a hundred days, there’s a hundred days of programming. It takes off different sections on each day.

TM: Do you start with the technology first or the concept first? What gets a new artwork going?

RA: There’s a spark that triggers something that grows. For instance, there was a recent work at IMA and it was just three drips of water onto a book. It was A.O. Neville’s book, Australia’s Coloured Minority [Neville was a British bureaucrat in the early 1990s, officially titled as Chief Protector of Aborigines] and it was sitting on a rock on a large black plinth with ochres within the pages. And over time it’s eaten into the book, into the pages, and all the ochres dribbled out. Each day it flowed down the long plinth. It came from seeing that book—and being someone who explored Chernobyl in school—and seeing a book sitting there with knowledge, this text being slowly eaten away by water. It was this idea of time and the power of a drip of water.

Then seeing this movement and change within Indigenous culture, this constant movement of it. And also taking away the power of that [A.O. Neville’s] language too. It was a cathartic piece.

It’s this back and forth between them [the technology and concept] and I don’t just go, “Oh, I like lasers. I want to make work with lasers.” As much as I like lasers! Instead, I want to use the tool, the mechanism as well as design—and I make all the mechanisms myself, so I’ve got that control over the aesthetic to a degree. But people look at it and say, “Oh, where do you buy those from?” As if it’s off the shelf, which is good because I’m wanting to make a mechanism, but having that subversion of the mechanism not being the focus. And I have to have the idea of the mechanism because I’ve always got to know how to achieve something. I’ve got to start a work knowing that I can make it, rather than having these grand ideas of laser beams [laughs].

TM: Going back to what you said about the colonising effects of language—your works show this so clearly, even the font you choose, it has that impact of language being linked to power dynamics. Has language always been important to you in that way?

RA: It’s interesting, something I struggle with is language. There’s always been a disconnection for me with ideas and being able to articulate things or comprehend things without constantly going over them. At times it makes me frustrated, but I see some parallels with coming into someone’s culture and taking away something that has their whole knowledge system, their strength of ideas, and their place within the Country—and taking that away and forcing them to use another language.

This was strongly encouraged everywhere within Australia with all Indigenous speakers, and it’s something I’ve only got a little insight into with my own difficulties with language. This is a tangent, but I’ve seen A.O. Neville’s rejection letter to my great-grandmother for her application for citizenship, saying that she was ‘mixing’ and hanging around with other Aboriginal half-caste girls: there was implications of language within it. It’s this idea that you’ve got to speak the language and ‘do as we do’ to get the benefits that we get.

But still, there’s a revival language in a lot of places that have lost that connection. And Tasmania is one of those places that has lost that connection to their language and are reconstructing it from the words found in Western explorers who’ve gone through and written these down.

TM: How does it feel at the end of a palimpsest work when you see that Yawuru word on the gallery wall?

RA: I don’t like to talk about translation, but it’s like a translation of emotion. With the palimpsest works, sometimes I miss seeing the end of it. But when I do [see the end], it’s a moment. Definitely a moment. I don’t know whether I could put it into words because it’s something I can only imagine. I don’t have the luxury to have a work that goes for three months in my studio to see it. So then being there and seeing that word within that space—it lives. There’s an energy. The end is a critical point where it becomes cohesive as a whole, as that artwork. And knowing how well the oxides stain, even if they paint it over it’s still held within those walls. Also, that first spray onto the white surface is a moment as well.

TM: As we speak, you’re currently preparing for an exhibition at Mona, collaborating with Aboriginal linguistic consultant Theresa Sainty. How did that come about and what will you exhibit?

RA: I was made aware of Theresa and her work—she’s undertaking a PhD in looking into language and place names. I put my proposal towards Mona, wanting to collaborate with the traditional owners and knowledge holders of that area—and Theresa was brought to my attention as having that strong connection to language. Whenever I collaborate with language within the work, it’s always a different story of where the language is, and who’s speaking it. It gives a deeper insight into the places.

Theresa and I have been going back and forth, chatting about the works, and they’ve evolved over time to sit within the language, sit within the Country. Theresa’s gifted me a group of words for each work—there’s two main works, a video work and a soil work—but you won’t see or hear any of the words in parts of the work. It’s where a combination of different works have come together, and you’ll see how there’s also cutting into the rock, and revealing the sandstone and the layers within the sandstone. So it’s talking to Theresa and understanding the words of that place, then moving my work at the component level to talk about that Country and that language.

Within an utterance

Robert Andrew

Mona

(Hobart TAS)

Until 17 October

This article was originally published in the July/August print edition of Art Guide Australia.