Working from his inner-city Sydney garage, Remy Faint meticulously constructs every element of his artworks—handcrafting wooden frames for his layered silk paintings, sculpting fabric, and, recently, engineering a large architectural structure inspired by 19th-century mechanical looms.

A deep engagement with both personal and collective history runs through Faint’s ever-evolving practice. His work is shaped by his family’s migration story—his great-greatgrandfather, James Chung-Gon, arrived in Australia from Southern China over 150 years ago during the Victorian Gold Rush. After facing discrimination, he became a household name in Launceston, Tasmania. Faint’s great-greatgrandmother, who came from a lineage of silkworm farming, brought with her a legacy that now finds its way into the artist’s material explorations. Today, their personal belongings are preserved in Tasmanian museums as artefacts of early Chinese immigration to Australia.

This lineage informs Faint’s work, which is deeply rooted in object history and the ways material culture shapes personal identity. With his striking, multilayered paintings, Faint transforms personal, historical narratives into contemporary expressions of cross-cultural identity, reflecting the innovative spirit of those who build anew while honouring the past.

Place

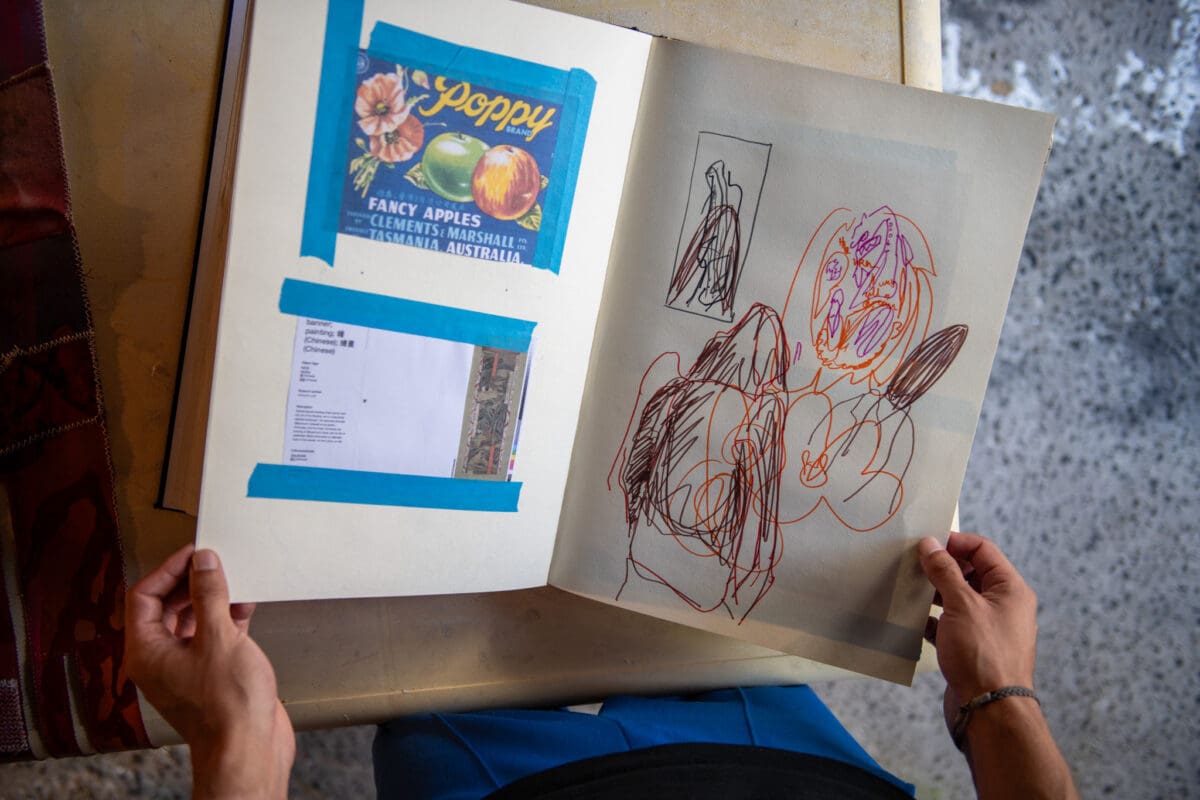

Remy Faint: The collecting and archiving of different materials is prevalent in my work. If there’s an element that I don’t end up using I usually put it away for a period so that the studio acts as both storage facility and archive. It’s quite fluid because I work across a few different processes, including painting, ceramics, stitched fabric and at the moment I construct a lot of my own frames. The space goes through different phases depending on what I’m working on.

It’s both my own and a shared space with housemates who need to access it, as it is a garage—so everything is frequently moving around. The space has its quirks, such as its susceptibility to water after a storm, so things are usually elevated.

People say my works appear delicate due to the transparency of the silk, which to some degree they are, but I think as a part of the entire fabrication process and this environment, they are actually quite robust. Assembling and collaging materials is central to my current practice, so I quite like it if the works show nuances or discrepancies.

Process

Remy Faint: In my formative years of art-making and understanding my family’s history, my Chinese heritage was often expressed through heirlooms—mainly ornaments, clothing, textiles and trinkets owned by my ancestors. When I started experimenting with silk as a painting surface, I kept scraps and other tests as an archive in reference to this object history. These often end up coming back into the works.

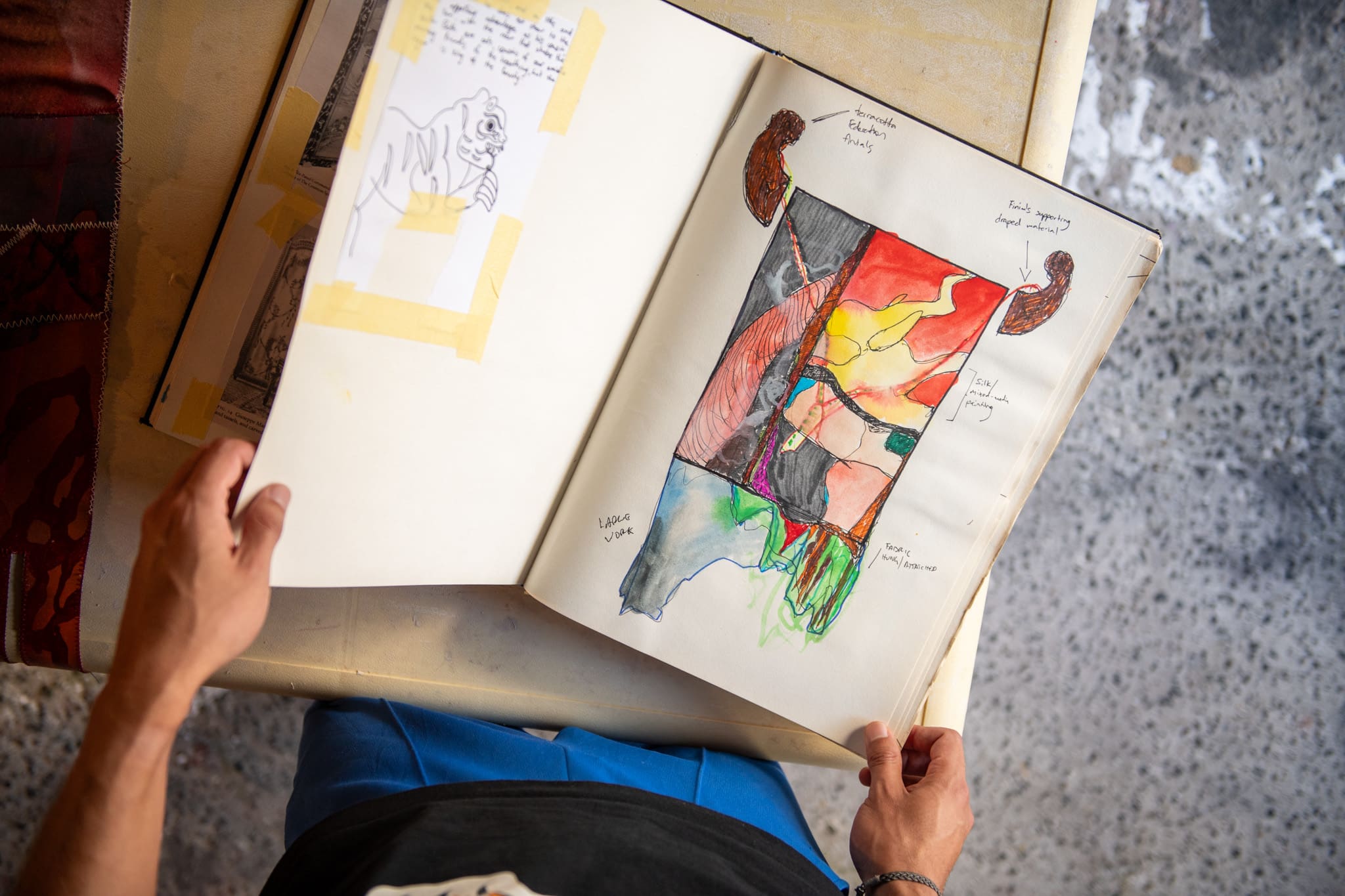

In my paintings, I usually start by fabricating the frame with seemingly ornamental, irregular wooden brackets. This element adds support to the frame, and is a key layer in the development of the composition, suggesting a portal or passageway. The silk material is then stretched onto the frame where I use a spray gun to add swathes of colour. This acts as an initial painted ground, and imitates tonal depth in the transparent surface. From there it’s a process of layering painterly gestures. This can be abstract, or inspired by reference imagery that has been mediated, sometimes digitally or straight onto the surface. I reference archival or photographic imagery in almost all my paintings.

Painting on silk is completely different to painting on canvas. It is a much finer material and doesn’t absorb paint like primed cotton or linen. I have to paint thickly and use various acrylic mediums to get the right consistency and fluidity. I can work quickly because of the brief drying time of acrylic but it’s quite hard to ‘fix’ any mistakes. In a way it mirrors calligraphy techniques.

I then start to collage materials to create opacity. This is when my archive of painterly fabric surfaces is employed. A collaged banner or sash has become quite consistent within a lot of my paintings. They have often been described as horizon lines. For me, it is a reference to those textiles that have been a part of my family. This part of the process can be more spontaneous than the painted elements, as I am experimenting freely and quickly with different textures, colour and materials.

Projects

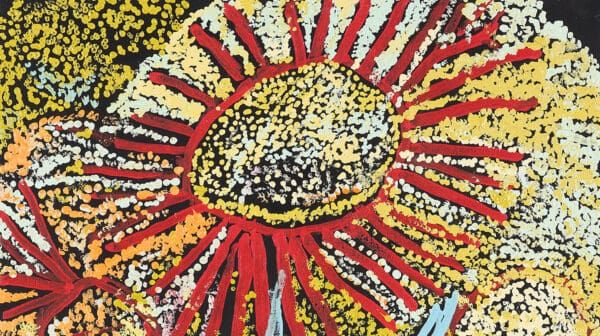

Remy Faint: In the group exhibition Artists in CQ: Of the Region, at Rockhampton Museum of Art (RMOA), I’m showing an iteration of an installation presented last year in the Create NSW Visual Arts Fellowship (Emerging) at Artspace (Sydney). The RMOA exhibition brings together artists of Asian heritage with ties to the region. I’ve created new paintings specific to the narrative of Rockhampton’s regionality, and Central Queensland more broadly. Although my Chinese side of the family isn’t from Queensland, I’m connected to this show because my father’s heritage and family is rooted across that area. The way this piece works alongside its previous iteration is a reflection of the parallel narratives of my identity.

My new paintings refer to newspaper illustrations from the Queensland State Archives that depicted Asian immigrants. The imagery is abstracted and mediated creatively, attempting to reposition a dominant view of history.

I was interested to have these painted compositions in relation to the main sculpture which is based on the form of a large 19th-century Chinese mechanical loom. Architecturally it creates a field of different materialities. It corresponds to the narrative of the loom, which is about transforming material from its raw state.

I wanted to prioritise this state of change that is occurring between different objects, gestures and forms within the installation.

Alongside Artists in CQ is Made in Japan, an exhibition featuring 19th- and 20th-century Japanese standing and folding screens from the RMOA collection. These types of screens have had a long-term influence on my work. I’m excited for my work to be positioned adjacent to a vernacular collection of objects.

Exploration of identity shaped by a context of archiving and collecting has always been important to my practice. It’s certainly why I’m drawn to silk: not only for its history as a painting surface, but its transcultural importance across 15 centuries of Silk Road exchange and culture.

Artists in CQ: Of the Region

Rockhampton Museum of Art

(Rockhampton/Darumbal Country QLD)

On now—3 August

RMOA Collection: Made in Japan

Rockhampton Museum of Art

(Rockhampton/Darumbal Country QLD)

On now—24 August

This article was originally published in the May/June 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.