Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

“Beaches,” the French auteur François Ozon has said, “are timeless spaces, providing abstraction and purity.” But the shorelines of his films rarely endow clarity upon their visitors. Instead, they are sites of foam and ferment where life’s great quandaries—mortality, morality, destiny, desire—come to wrestle in the shallows. Most potent, perhaps, is his 2000 drama Under the Sand, where the husband of an English professor (Charlotte Rampling) vanishes during a seaside holiday. Rampling plays a woman circling the brink of neurosis—haunted as much by the spectre of her husband as the vagaries of the ocean. No tangible conclusion ever emerges. The camera gazes into the tides, searching for hints. Might they augur doom or divine intervention?

A portrait of Charlotte Rampling appears in Impossible Island—the Art Gallery of Western Australia’s (AGWA) new survey of the Haitian-French photographer Henry Roy spanning four decades of his career and 113 works. In shallow focus, Rampling tilts her head just slightly away. Like her character in Under the Sand, she telegraphs a stoic poise disguising some private heartache. “She had been absent from the screen for several years” when the portrait was taken, Roy recalls over email. The Ozon film marked a grand return for Rampling, who had previously suffered a decade of depression and ghoulish tabloid coverage of her husband’s infidelity.

The shoot, says Roy, “unfolded with remarkable ease”. The encounter hardly feels surprising for a photographer who has long been entwined with cinema, counting French New Wave, Ingmar Bergman, and early Terrence Malick among his influences. With Ozon, he shares a fascination with water: its vitality and its rippling mysteries. “I am irresistibly drawn to rivers, the sea, and even certain swimming pools,” he says, citing their “profoundly unsettling concentration of the energies of life and death”.

In water, you might discover clues of Roy’s lineage. He was born in Haiti to a soldier father and a mother who was the sister of an army colonel. In 1966, when he was three, the family moved for political reasons—an event he now considers his “exile”. Roy’s upbringing was peripatetic: uprooted from Port-au-Prince to the south of France, then into the suburbs of Paris, where he was enrolled at a stuffy secondary school “that trains the intellectual elites of the country”.

His parents had no interest in art, and he fell into photography by chance: when he was 18, a friend “invited me to watch the development of a photo in his darkroom”. Seeing images bloom from the shadows felt like an act of divine creation. “I decided that I would make a living from this alchemy,” he says. All the while, his recollections of his mother country, his mother tongue, had slowly eroded. When he returned to Haiti for the first time at age 25, the island of his birth was little more than a dream. “Although some things were familiar to me—the sound of the language, the scents, the food—I felt like a stranger there. I was, in fact, perceived as one by the locals.”

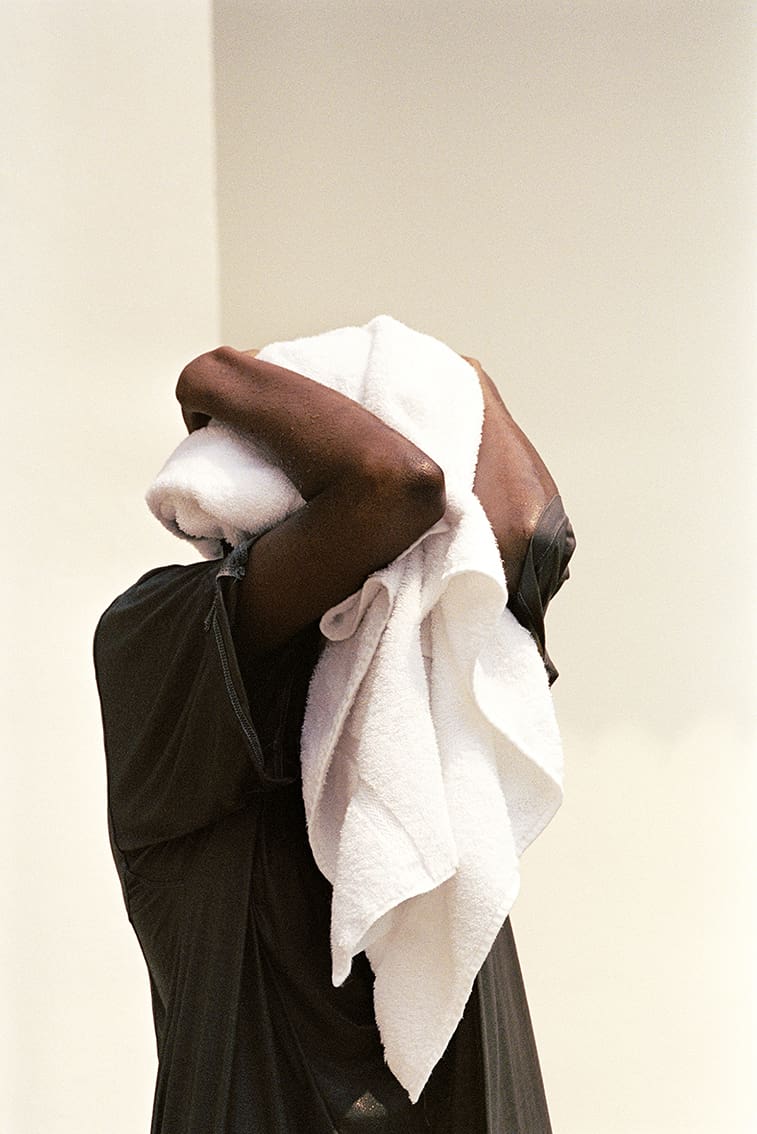

Roy’s work, then, is an exercise in recouping the homeland wrenched from him as a child. “I became an obsessive islander,” he says. “The quest for the lost island led me to the four corners of the globe.” In the 90s, he met Elaine Fleiss, the co-founder of iconoclastic fashion publication Purple. He began working with the magazine in a collaboration that lasted a decade—with no pay but total artistic freedom. “I was the only Afro-descendant in this environment,” he says. His photographs spanned famous figures—including his portrait of Rampling—as well as his travels across Africa and Europe: assemblages of locals sleeping, swimming, and showering, always illuminated by a light so brilliant it threatens to burn through celluloid.

Travel, says Roy, “is a way to step outside reality”. So is his new survey, whose title—Impossible Island—implies “an imaginary refuge where one can escape the brutality of the world”. Images of coastal arcadia abound. In Man walking, Jamcel, Haiti, 2016, a figure paces the waterfront, oblivious to—or perhaps deliberately neglecting—the furniture strewn behind him. A throng of bodies in Wrestlers, Dakar, Senegal, 2016 writhes and ripples across a stark expanse of white sand, recalling the sun-bleached eros of Claire Denis’ Beau Travail. (Denis herself also appears in the exhibition alongside fellow film directors Mati Diop and Jonas Mekas.) Again and again, subjects idle by the sea, limbs akimbo and eyes closed in repose or rapture.

One of the show’s most transportive images—Es Vedrà – orange, Ibiza, Spain, 2004—captures a twilight off the Ibizan shoreline. Look once, and observe the sky and its rutilant glow, a hue that hardly seems borne of this mortal plane. Look twice, and gaze at the ocean roiling beneath the craggy outpost. Look again, and you might start searching the waves for prophecies. “I seek a kind of magic,” Roy says. “I look for epiphanies.”

Henry Roy—Impossible Island

Art Gallery of Western Australia

30 November—18 May