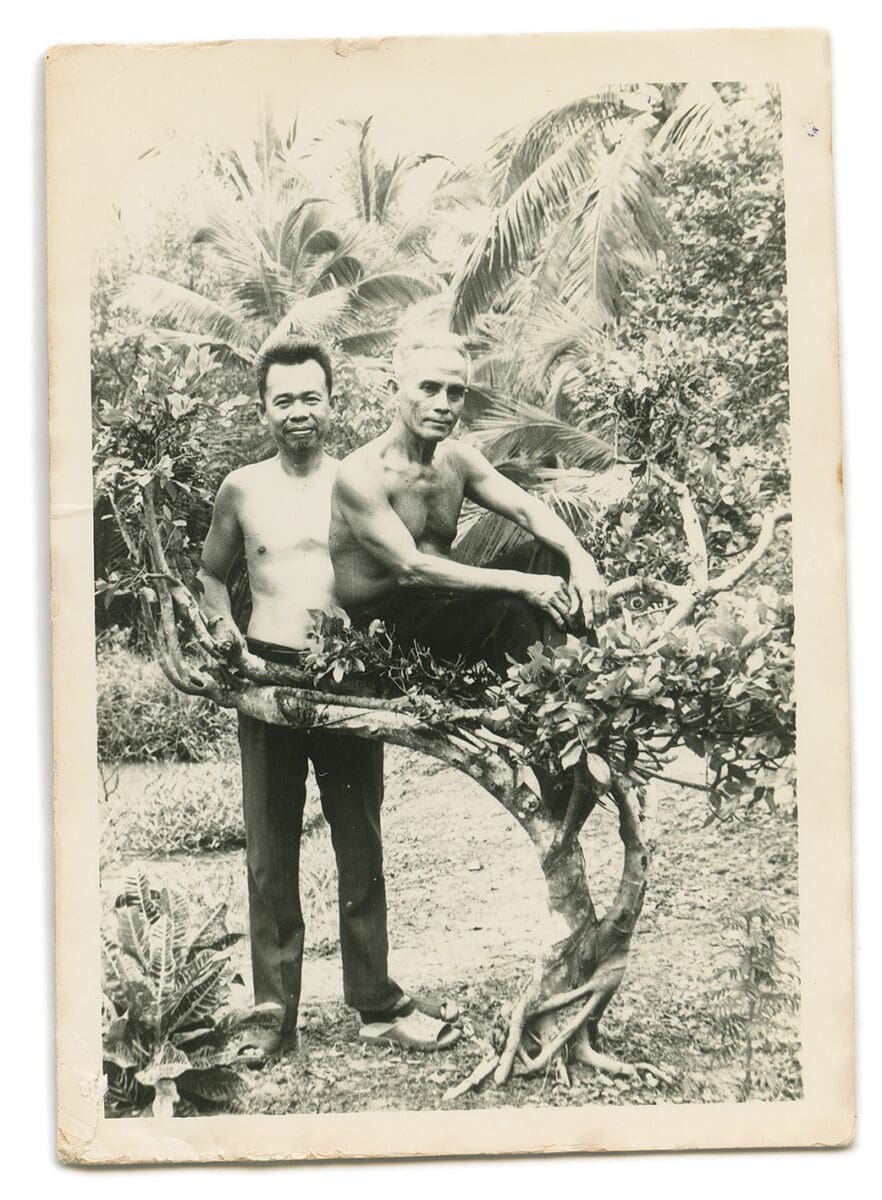

The story of Inheritance is an epic: it spans generations and continents, incorporates objects bought and sold across family lines, and draws on both spiritual and everyday rituals. At times over its long development, Phuong Ngo tells me, he wondered if the project might be cursed. After three marble table tops, produced near his family’s village in Vietnam, shattered upon arrival in Melbourne, a good friend asked if Ngo had requested his ancestors’ permission. Ngo started burning incense and offering cognac, and things improved.

Inheritance is full of mysterious confluences, complex family lore, wry humour, and tough love. It’s centred around the family table: a site of gathering, meals, celebrations, and punishments. There are the tables with marble tops (successfully re-made) based on the ones from Ngo’s maternal family home in Vietnam, their legs fabricated from the timber frame of the ancestral home. There’s a table purchased from one side of his family into the other, becoming a kind of self-portrait of the artist. Then there is the second-hand melamine table that was at the centre of Ngo’s Adelaide childhood.

There are particular kinds of punishments that, Ngo explains, are familiar to many second-generation Vietnamese-Australians. They involve holding poses and postures for extended periods, either against a wall or over a table. Punishment can be traumatic, but Ngo views them with nostalgia, even humour. For Inheritance he is collaborating with emerging Vietnamese-Australian artists, exploring what it means to hold these body memories. Just like the charged objects that populate the show—the tables, his mother’s jade earrings, his grandmother’s therapeutic coins—these postures are an inheritance. And here, Ngo is thinking deeply about what he will pass down to the next generation.

Inheritance

Phuong Ngo

West Space

On now—7 June

This article was originally published in the May/June 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.

Coinciding with the exhibition is the release of Ngo’s new photobook of the same name, published in collaboration with Slow Burn Books. The book is launching as part of the Melbourne Art Book Fair, see details below:

Photobook Launch: Inheritance by Phuong Ngo

West Space

Saturday 24 May