When Patrick Brown set out to capture the vast open spaces of Western Australia, he assumed it would take a couple of weeks to shoot. Yet his photographic mission, to explore the negative space between objects, took more than a year of shooting landscapes, from coastal Shark Bay to the dusty goldfields region of Leonora and back to Perth again.

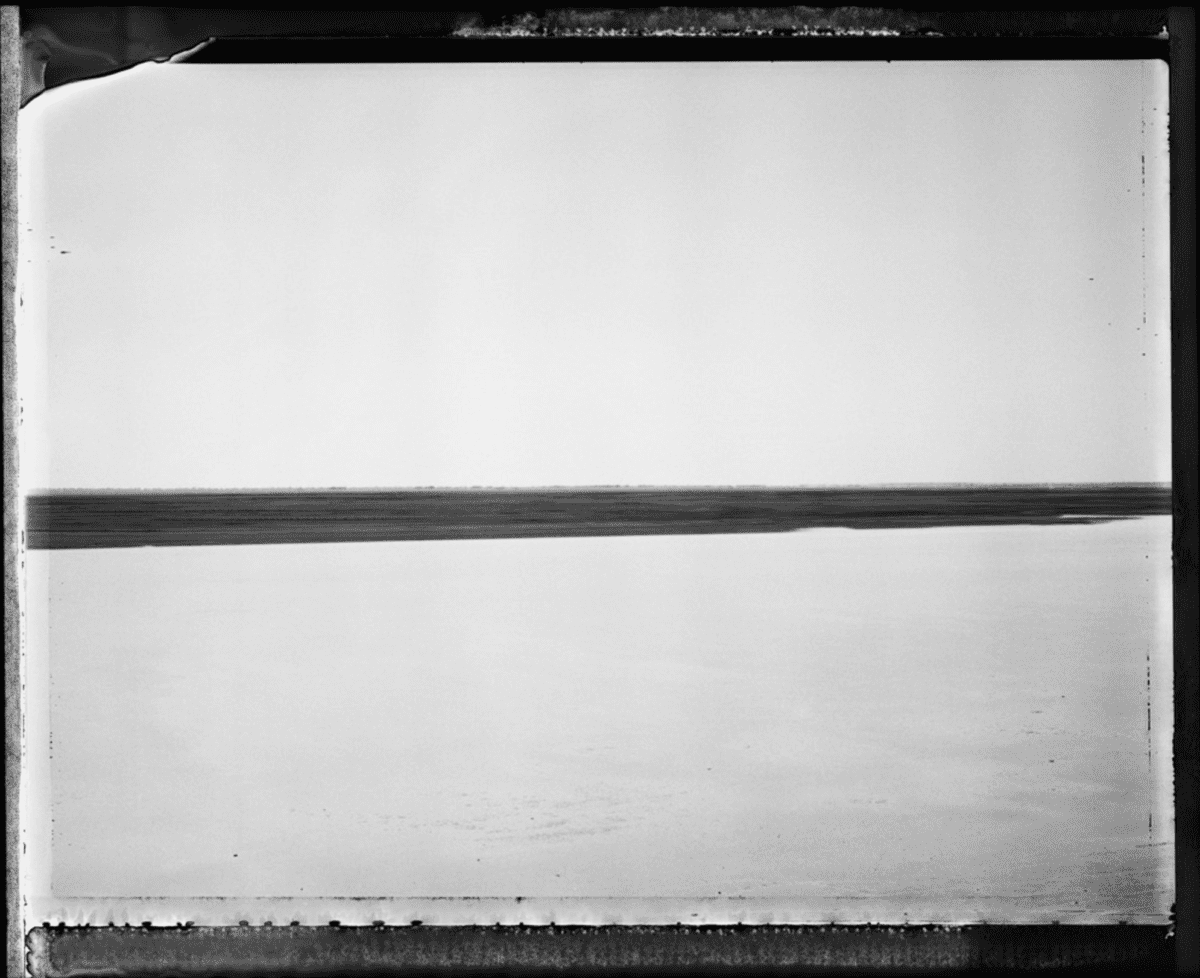

In the first tranche of a series he calls Hope, the Sheffield, England-born artist, raised in Perth from age 12, has created a series of monochromatic prints shot on now discontinued Polaroid 665 positive / negative film.

“I was fascinated by the ambiguity of ‘hope’, which is always perceived in a modern context as a positive word,” he recalls from his home in Copenhagen, where he moved two years ago after marrying a Dane whom he met during his two decades living in Thailand.

Hope, says Brown, is shadowed by doubt, right down to the chances of survival when specific environmental knowledge might be lacking: “Out there in the bush, especially out there in the plains, the balance of life is so fragile for human existence.”

Brown frames the horizon line in the centre of these hauntingly stark Western Australian images, as a place where ostensibly binary notions of hope and doubt, yin and yang, right and wrong, positive and negative meet and bleed.

When he started the project, “I was a little bit arrogant, I thought doing landscapes would be quite easy, it would be over in a couple of weeks, and I learned a very valuable lesson. Landscapes are not easy, you have to really connect with them, and it took me some time to be out there, to really understand the elements that I was working with.”

Brown’s ecological concerns dovetail with his career to date, which has been built on critical issues often ignored by media. His series Trading to Extinction, for instance, graphically captured the commodification of wildlife, while No Place on Earth poignantly documented the persecution of Rohingya people.

When the Asian tsunami hit in 2004, he was standing on a hillside in the Philippines by a volcano with a shortwave radio, listening to BBC reports coming in about the disaster, when a geologist was interviewed.

“The geologist said, ‘We live on the equivalent of an apple skin’, and that the only reason life exists on the planet is because of ‘geological consent’. I’d never, ever seen the world like that. I was sitting on the hillside of an inactive volcano, listening to how the Earth is communicating with us: she is moving; she is evolving.”

The world that humans see is “only one perspective”, says Brown, and “that geological consent could be taken away at any moment.”

The geologist’s statement “led me ultimately to Australia, to try to find my definition of what this apple skin was, hence the horizon line is always plum centre in the frame.”

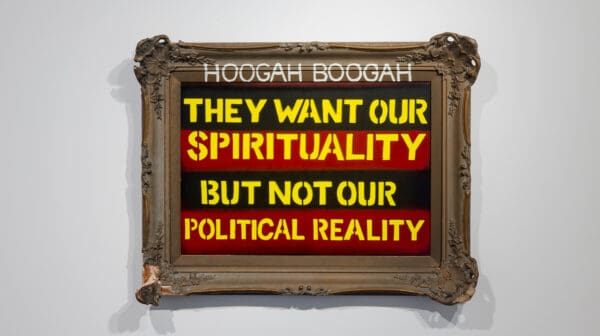

I ask Brown that whether we can ever know these seemingly inhospitable landscapes culturally, spiritually or philosophically if we are not Indigenous, if we lack Aboriginal knowledge to deeply listen to Country.

“Where the Indigenous people of many cultures excel compared to the Western ‘scientific’ avenue is they always have a much deeper connection to the fragility of life, and they need to know the land to survive, they need to know the land intimately to be able to harvest what it can give them and protect them,” he says.

“We all need to recalibrate and readjust ourselves to the land that we live on. Not in a whimsical way, but in a real concrete manner [in order] that we will survive. The Indigenous populations around the planet innately understand that.”

Brown chose to use Polaroid 665 because it is a “beautiful” positive/negative film. “You pull it apart and there is a positive photograph, and there is a negative, and the positive is a by-product; you’re after the negative,” he says.

“Just by your biomechanical action of pulling the film out of the film back, you can totally change how the image looks: it can tear the emulsion; it can get roller marks in there.”

Production on the film stock has ceased. “Even the baseline of the visual literacy of the image is built on that extinction and that one-off capacity and uniqueness of each frame,” he says.

Next, Brown hopes to take the Hope series global, going to the Antarctic, into South America and off into the deserts of Mongolia. “It comes down to my personal relationship with the planet, and trying to articulate it in such a way that people can digest it.”

Hope

Patrick Brown

Art Collective WA (Perth WA)

16 September—14 October