Reframing a Collection

Drawn from the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art at the University of Western Australia (UWA), Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery’s show Place Makers, reframes the artists—who just happen to be female.

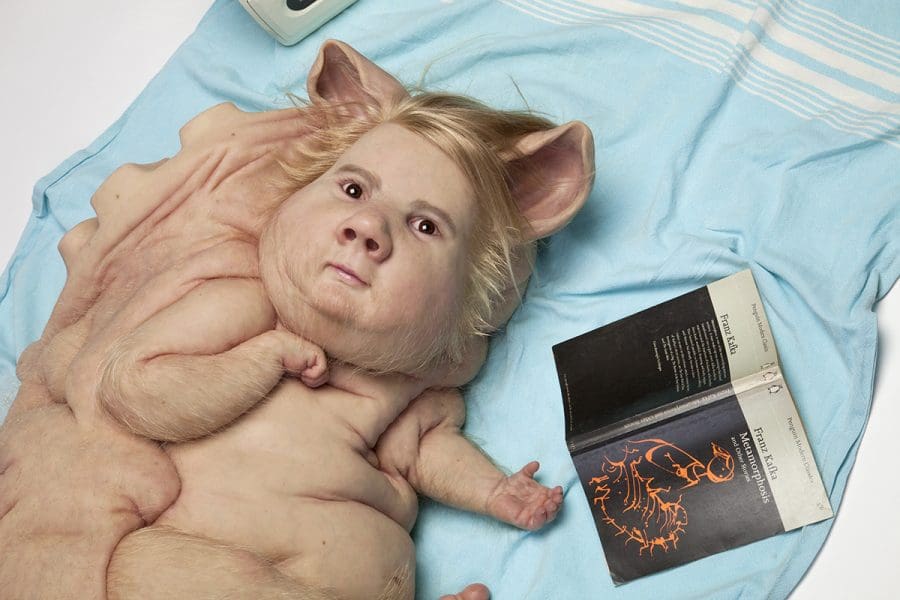

Patricia Piccinini, Teenage Metamorphosis, 2016, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, found objects Figure:25 x71x52cm, Overall dimensions: 137 x 25 x 75 cm. Edition of 3, 1AP Edition 1/3.

Patricia Piccinini, Teenage Metamorphosis (detail), 2016, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, found objects Figure:25 x71x52cm, Overall dimensions: 137 x 25 x 75 cm. Edition of 3, 1AP Edition 1/3.

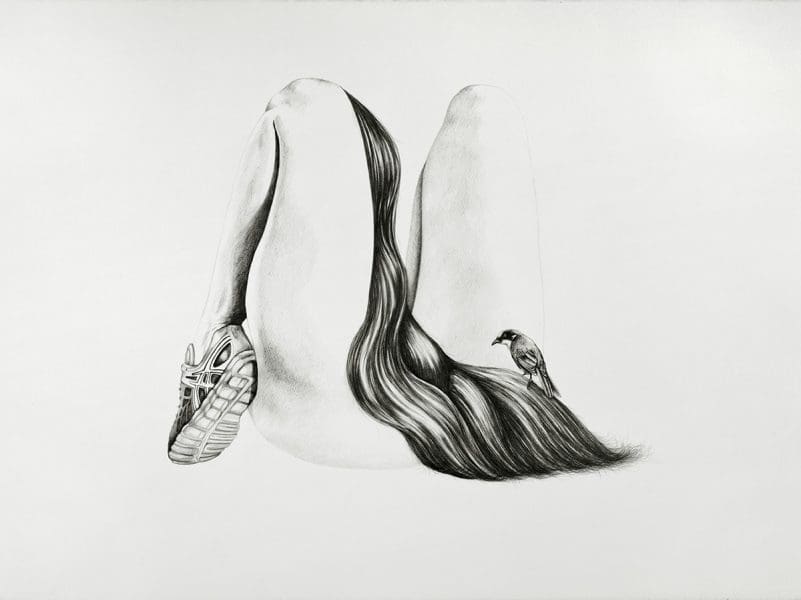

Patricia Piccinini, Poised runner, 2017, graphite on paper, framed 57 x 76 cm (paper size) 72.5 x 91 cm (framed size).

Patricia Piccinini, Unfurled, 2016, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, found objects Figure: 71 x 25 x 52 cm. Overall dimensions: 108 x 89 x 80 cm. Edition of 3, 1AP Edition 1/3.

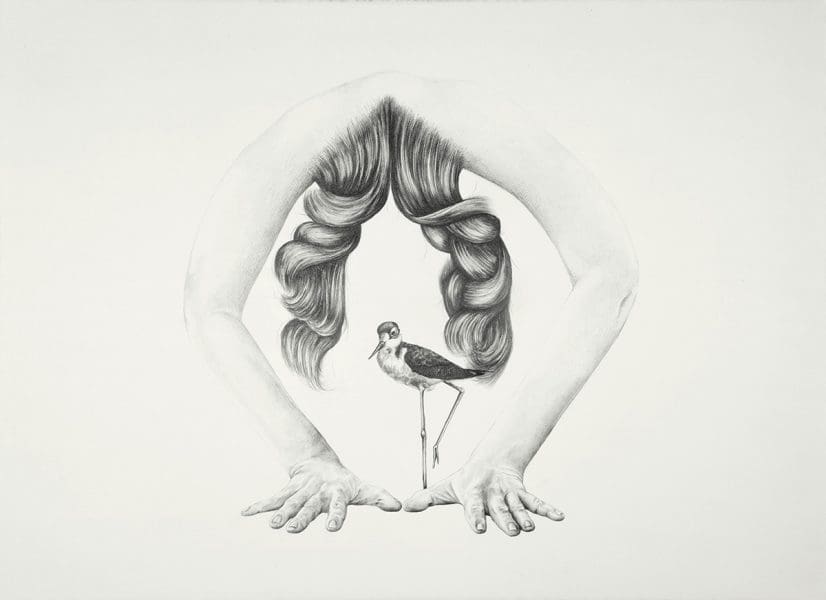

Patricia Piccinini, Guarded entrance, 2016, graphite on paper, framed 57 x 76 cm (paper size) 72.5 x 91 cm (framed size).

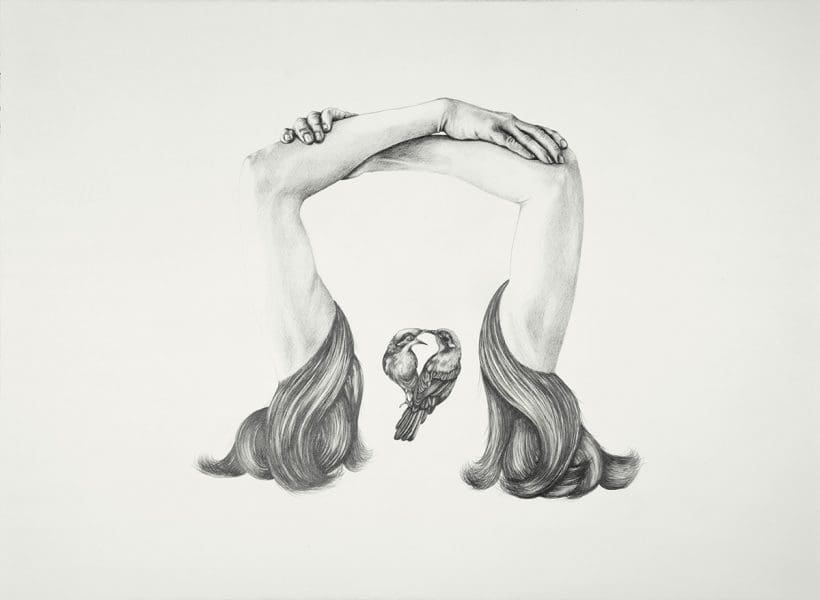

Patricia Piccinini, Bridged connection, 2016, graphite on paper, framed 57 x 76 cm (paper size), 72.5 x 91 cm (framed size).

Patricia Piccinini, The Naturalist, 2017, silicone, resin, human hair Figure: 26 x 34 x 27 cm. Edition of 6, 1AP, Edition 1/6.

Patricia Piccinini, The Osculating Curve, 2016, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, Figure: 54 x 72 x 30 cm. Overall dimensions: 103 x 128 x 103 cm. Edition of 3, 1AP Edition 2/3.

Patricia Piccinini, The Osculating Curve, 2016, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, Figure: 54 x 72 x 30 cm. Overall dimensions: 103 x 128 x 103 cm. Edition of 3, 1AP Edition 2/3.

Patricia Piccinini, The Osculating Curve, 2016, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, Figure: 54 x 72 x 30 cm. Overall dimensions: 103 x 128 x 103 cm. Edition of 3, 1AP Edition 2/3.

Patricia Piccinini, The Naturalist, 2017, silicone, resin, human hair Figure: 26 x 34 x 27 cm. Edition of 6, 1AP, Edition 1/6.

Patricia Piccinini, Unfurled, 2016, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, found objects Figure: 71 x 25 x 52 cm. Overall dimensions: 108 x 89 x 80 cm. Edition of 3, 1AP Edition 1/3.

Patricia Piccinini may have made headlines with her Skywhale, 2013, or more recently with Graham, a sculpture used in education about road traffic accidents, but it’s her quieter works that make the biggest impact.

In her latest exhibition, No fear unmingled with hope, Piccinini both works with and moves beyond the anthropomorphism common in her previous works and incorporates more than ever the side of nature in the equation of man vs machine. She seems to ask: What role does the natural world play in a global culture of climate change in which bio-technological changes are taking place at increasingly rapid rates? Sitting smack-bang in the middle of the exhibition is the sculpture Unfurled, 2016, which depicts a stuffed owl in mid-landing on a child’s shoulder. The child seems attentive to something bigger than herself. She sits on a yellow, modern one-seater sofa that aesthetically looks like it’s mimicking one of Piccinini’s automotive works, although it belongs very much to the domestic sphere. This work embodies an inexplicable relationship between domesticity, wonder and the natural world.

They are all powerful, in and of themselves, in their ability to reimagine form. But perhaps the most powerful is the artist’s Self portrait, 2015, in two parts. The top half features a raised fist protruding from a mop of hair; a feminist call. The bottom depicts the groin of a woman in which the pubic hair extends to shape another mop hair, like a waterfall, that is held by legs that transform into arms.

Known for her clever conglomeration of wonder and realism, the artist doesn’t stray far from these tropes in three more sculptures, each as sensitive as each other. The Osculating Curve, 2016, is reminiscent of Piccinini’s now-famous work, Protein Lattice, 2000, in which humans interact with mutant rodents as a response to the Vacanti Mouse (otherwise known as the ear-mouse) only this newer sculpture features oval-shaped mouths with slick lips perched on the torso of a woman with long hair. The sculpture sits on a geometric mirrored plinth, a fascinating choice of display as the bodies of gallery visitors are drawn into the sculpture. It represents the artist’s exploration of desire within the subconscious, and it invites others into that exploration. Resting on a towel with a boombox and a copy of Metamorphosis byFranz Kafka, Teenage Metamorphosis, 2016, a half-human half-shoe, on the other hand, draws you out of the subconscious and into the everyday.

In his latest book, The Great Derangement, Indian author Amitav Ghosh tracks the move in [Western] literature from a kind of imagination that involves holism and an acceptance or representation of the uncanny into an imagination that focuses inwards, resulting in humankind’s inability to look at the world as unpredictable. Piccinini’s practice resonates with this idea. She refuses to forget the uncanny and embraces imagination. Piccinini embraces uncertainty without fear.

Patricia Piccinini, No fear unmingled with hope

Tolarno Galleries

16 February – 18 March