What is the prospect for women artists in Australia in 2022? Today they are increasingly recognised, honoured, and, most important, emboldened. This was almost inconceivable 50 years ago, in the different world where we first read the celebrated Dorothy Dixer posed by American art historian Linda Nochlin, ‘Why are there no great women artists?’

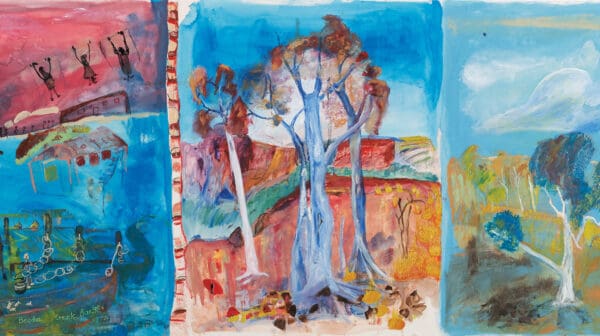

In 1973, when I first published an article mentioning Vivienne Binns, I could not have predicted her extraordinary career, or her 2022 major museum survey On and through the surface. But the die was cast in the 1970s, with the passionate advocacy and activism of the Women’s Art Movements, and now women are crucial to innovation in the arts, as elsewhere in society. This is no overnight transformation. It’s the culmination of decades of experiment, advocacy, comradeship (and competition), heartsearching, and sheer hard work. We have seen the diffusion, even the popularisation, of feminist art practices. And as a result, women artists (and writers, filmmakers, musicians) have reshaped the country’s imaginative life, making, as in so many fields—law, medicine, sport, business, education, theology—huge changes in society.

In recent years there’s been a huge acceleration in the recognition of the pernicious legacies of sexism, both here and internationally. I am thinking not only of the #MeToo movement since late 2017, with its resonances in Australia, but the courageous contributions made to public life in 2021 by Grace Tame and Brittany Higgins. Who could have predicted the great shift in community attitudes towards the indignities experienced by these (and many other) women? This has been amplified by public scrutiny that includes (among many distinguished contributions) Kate Jenkins’s report Set the Standard and Jess Hill’s Quarterly Essay ‘The Reckoning: How #MeToo is Changing Australia’. Such frank conversations about women’s status and expectations in Australian public and domestic life are signs of great change. And 2021 was a certainly a tipping point.

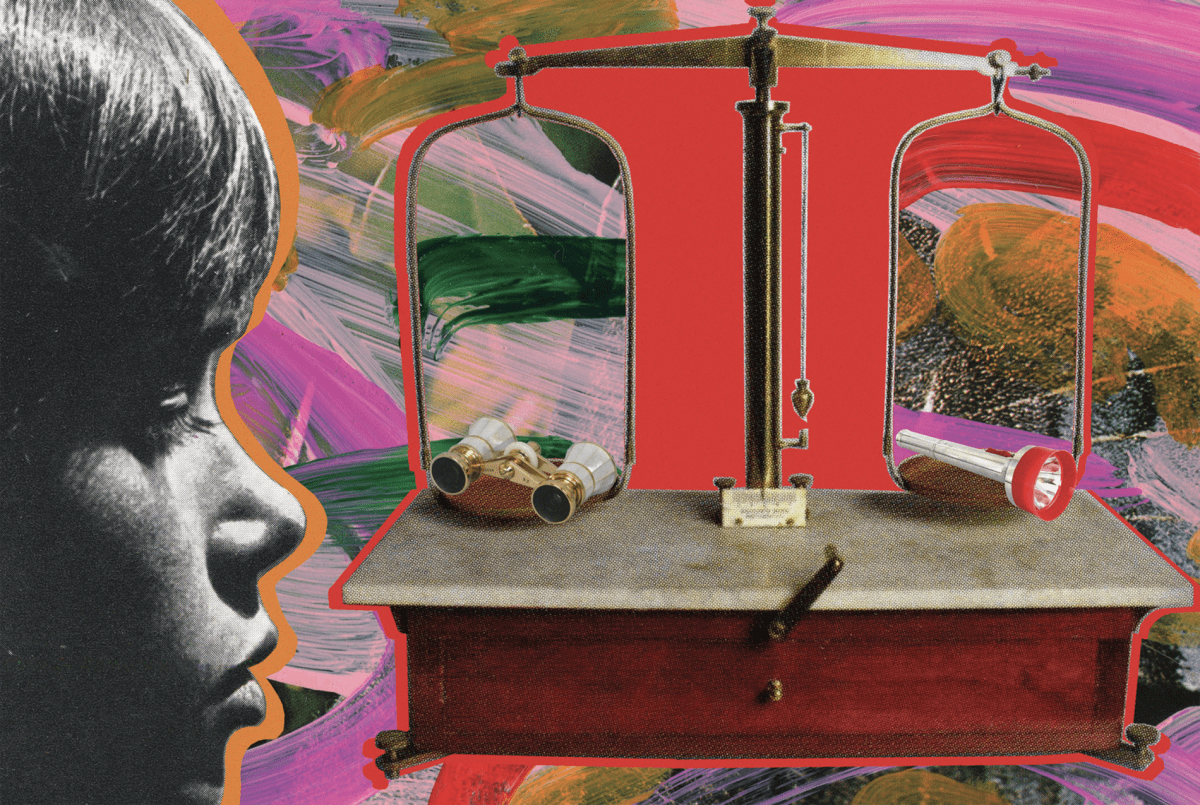

Artists have been central to these conversations: witness Sarah Goffman’s commissioned artwork for the The Monthly cover in May 2021 with the raw text ‘I believe her’. Drawing on home-made imagery from street demonstrations, Goffman summons activist wit and exemplifies continuing feminist advocacy. Not surprisingly, the visual arts world has seen signal developments in the last two years: the focus on women’s social and political struggle has fostered a climate of enthusiasm for both historical and contemporary art by women across Australian museums and galleries, and internationally in influential institutions such as Tate Modern, now committed to greater equity for women artists in exhibitions and collecting. And the Countess Report, most recently delivered in late 2019, has partnered with the National Gallery of Australia in its multi-pronged Know My Name project, contributing to the NGA’s Gender Equity Action Plan, which will be released for International Women’s Day.

Know My Name is the most prominent of many Australian projects advocating for women artists, and an internationally significant exemplar. It was launched in November 2020 and the exhibition has been extended until June this year. Despite excellent intentions, the exhibition attracted informed criticism, as well as enthusiasm. About Know My Name’s claim to tell “a new story of Australian art”, critic Anne Brennan wrote in the thereviewboard, “That may be over-egging the pudding a little. Part 1 of the exhibition unpacked a narrative about the history of women’s practice that relied heavily on 40 years of feminist art historical scholarship.” And art historian Anne Marsh, writing in Artlink, made a similar argument in detail: her text is a valuable record of feminist achievement. As she argues, “In many respects, Know My Name is a belated response to the surge of interest in women’s art and feminism… ” Both are correct. To the mainstream, women and feminism have finally ‘arrived’.

Be that as it may, Know My Name remains a genuine “commitment and call to action”. Sally Smart, artist and NGA board member, put it plainly to the Sydney Morning Herald in June 2021: “Know My Name means nothing. This is just the starting point… It has to be about the intellectual space, as well as the physical space which gets handed over.” Part of that is the massive Know My Name anthology: the first edition of 3000 sold out, another 4000 are being printed. Together with Marsh’s own extraordinary compendium Doing Feminism: Women’s Art and Feminist Criticism in Australia, published in late 2021, there is complementary food for thought, teaching and debate in coming decades.

On balance, this movement seems unstoppable. Today Australians are accustomed to women being prominent in cultural life, offering fresh ideas and narratives underpinned by life experience and informed by rigorous theoretical positions. But while gender bias is morphing, it has not vanished in the last 50 years, nor will it in the next 50, I imagine: “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will,” as Antonio Gramsci famously imparted.

Today, though, I do take heart from the energy of younger artists, with their insight into the operations of cultural power and urgent demands for change. This impatience is valuable, it is necessary. It is directed towards results. It embraces new challenges. This moment has been reached through the robust practices of generations of artists, critics and audiences ‘doing’ feminism, to borrow Marsh’s title.

Commitment to change has fuelled this long struggle. And the brilliance of artists has fulfilled it in ways completely unexpected when feminist artists first gathered in the 1970s. This allows us to look to the future, when what today is considered extraordinary will have become expected, and when new and unexpected questions, problems and, one hopes, joys may be embraced.