Life Cycles with Betty Kuntiwa Pumani

The paintings of Betty Kuntiwa Pumani form a part of a larger, living archive on Antaṟa, her mother’s Country. More than maps, they speak to ancestral songlines, place and ceremony.

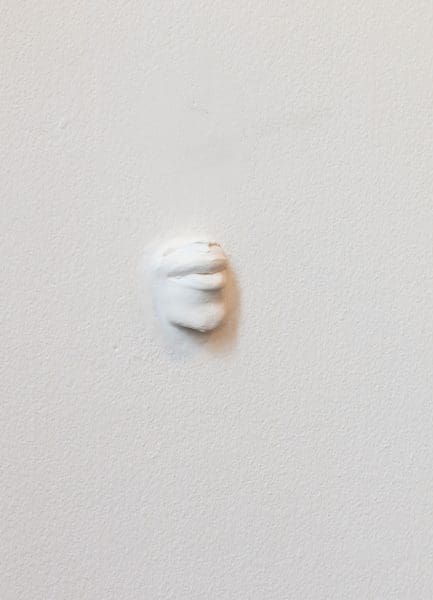

Installation view, Olga Cironis: Forest of Voices at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, 2020. Photograph by Bo Wong.

Installation view, Olga Cironis: Forest of Voices at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, 2020. Photograph by Bo Wong.

Installation view, Olga Cironis: Forest of Voices at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, 2020. Photograph by Bo Wong.

Installation view, Olga Cironis: Forest of Voices at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, 2020. Photograph by Bo Wong.

Installation view, Olga Cironis: Forest of Voices at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, 2020. Photograph by Bo Wong.

In Forest of Voices, Perth-based artist Olga Cironis invites audiences into an auditory installation of story and landscape. Over many months, the artist has been recording personal stories about love and connection told by a raft of volunteer participants. At Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA) visitors sit among a forest of hanging microphones, each issuing a whispered narrative, layered over the subtle thrum of the desert, water lapping on the WA coast, wind and raging fire. Sheridan Hart spoke to Cironis about working collaboratively with strangers, and the intimate catharsis that comes from speaking one’s experience out loud.

Sheridan Hart: The title Forest of Voices is poetic and mysterious. How did it come to you?

Olga Cironis: For me, forests are places of calm and reflection where I become aware of my breath and my presence among living entities that exist outside myself. In myths forests represent the subconscious and the untamed; a place where fear hides and answers appear.

I wanted to create an installation that poetically encapsulated this moment of listening, feeling and connection while exposing the fragility of humanity in today’s environmental emergency.

SH: What volume of recorded material did you gather in preparation for the exhibition?

OC: At present there are over 100 recordings: 68 hours and counting. The content is about the vulnerability of humanity, the power of love and desire to belong. One hears the shriek of a newborn, children playing, the laughter of old lovers, human breathing, and strong, aching, joyful and firm voices from diverse backgrounds.

SH: What prompts did you offer your participants before they made their recordings?

OC: The main thing I said was ‘Be yourself; to share a story that is special to you and explore what these feelings mean to you in the face of today’s world issues, including Covid-19.’

Altogether, the recordings tell a story about love. I don’t mean eros; I mean the journey to love, experiencing or remembering the lightness or heaviness of love. One participant spoke about escaping a war-torn country. Another read poetry. Others spoke about love of land, place, life or love itself. The language is intimate, and the stories come from the core of each participant.

SH: Were you present during the recordings?

OC: I realised early on that to talk about something intimate or personal or tragic, sometimes, people needed privacy. Sometimes writing a letter can be easier than confronting someone in person: this was the same. So instead I gave the microphone to people to use in their own time. I also invited people to send in recordings.

SH: Was anonymity an important aspect of the project?

OC: Absolutely. I edited out names and links to the contributors’ identities. Having said this, many participants didn’t mind being identified. Others wished for anonymity so as not to be linked to trauma or have loved ones recognise them. The anonymity of the voices highlights that our emotions, desires and experiences are linked, no matter what our history. We all have the same desire to survive, belong and be recognised.

SH: There will also be sounds of nature playing. Tell me about those.

OC: You’ll hear the four elements of fire, water, earth and air. For three months, I recorded my early morning walks because that is when I feel most at peace. Walking beside the river, ocean, in the desert and national parks; raging winter storms, birds waking, wind whistling through branches, the crackling fire. Human sounds are then linked to the natural elements that they cannot exist without.

SH: You foreground your contributors’ voices, while the signs of your creative touch are deliberately subtle. How would you describe your artistic role?

OC: All my work starts with experience, conversation, research and sometimes, basically, will or drive. I work very instinctively: the creative narrative is not always clear until the work is completed. Since my work is about humanity, it cannot exist without the public voice. I am not a lone wolf.

I guess my artistic role is to be inclusive, to listen, to learn, to drive the project and stay loyal to it. As a feminist migrant woman living in Australia, I know not to be silenced. It is my responsibility to make a difference because someone before me made that difference for me.

SH: You have a monograph coming out through Art Collective WA (ACWA). What was it like for you to look back on past projects while preparing the book?

OC: Where do I begin? It was, and still is, bizarre. Felicity Johnston and Loretta Martella at ACWA kept me from deviating and organised everything. Paola Anselmi, Jacqueline Millner and Lisa Slade wrote the essays and made me realise that there is still so much to do.

I also recognised that I refuse to be boxed in. I have never stayed loyal to one medium, yet there are materials I always fall back on such as cloth, feathers, gold, thread, metal and hair because of what they represent. Working on the monograph, I realised that art making is my language of communication and connection.

SH: What does it mean for you to have worked with so many public contributors?

OC: Back when I was first studying art, I became aware that the art galleries I visited were not very inclusive. Ignoring those social hierarchies, I decided to create art installations for everyone, not the few; artwork that people could feel reflected in and be a part of.

Without public participation, Forest of Voices could not exist. Public contribution is paramount. Working with so many contributors makes me feel part of something bigger than myself, which is very humbling.

SH: Will Forest of Voices continue on after this installation?

OC: Two new recordings just arrived on my doorstep. I will continue collecting recordings and hopefully Forest of Voices can be exhibited again with the additional edited stories.

Forest of Voices

Olga Cironis

Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA)

3 November – 10 January 2021