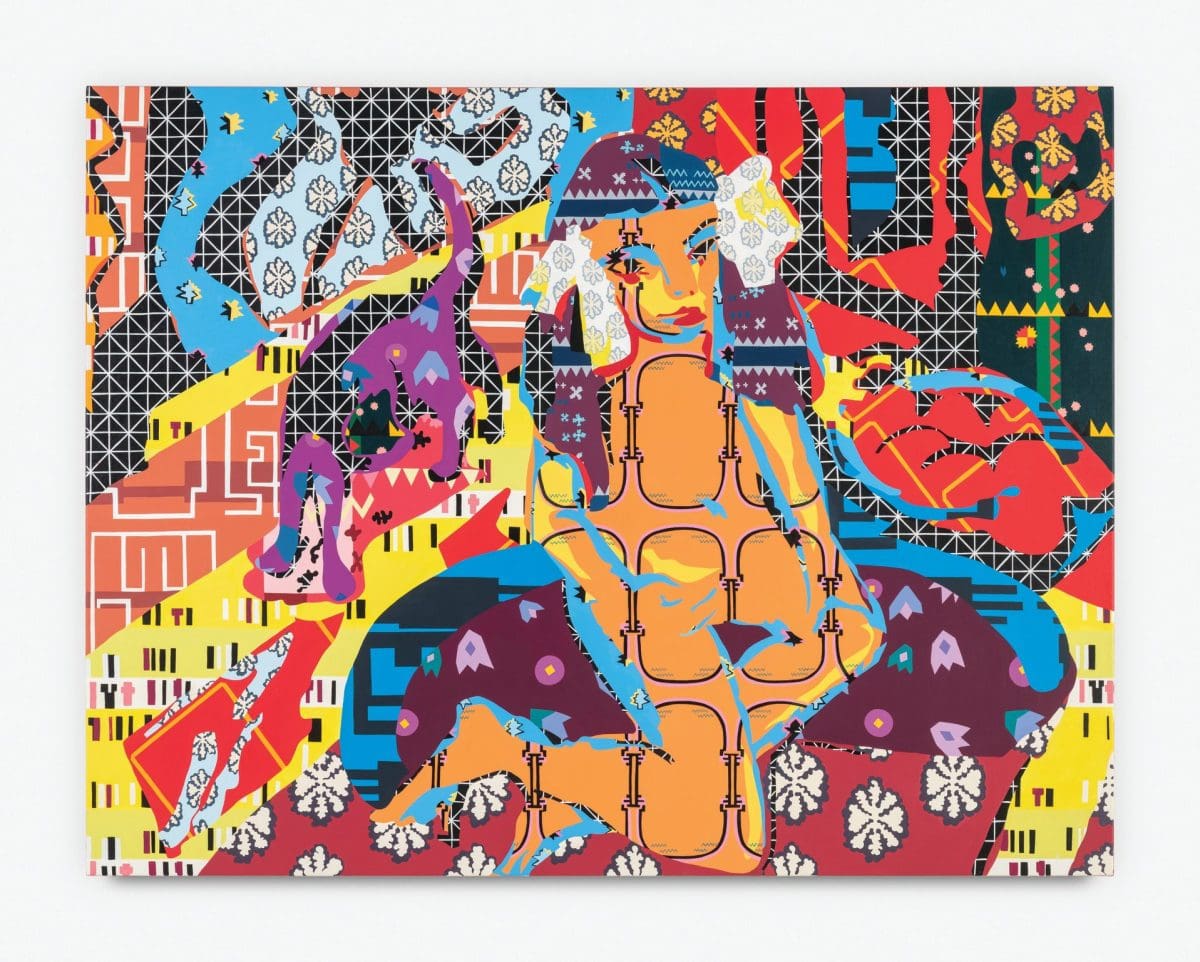

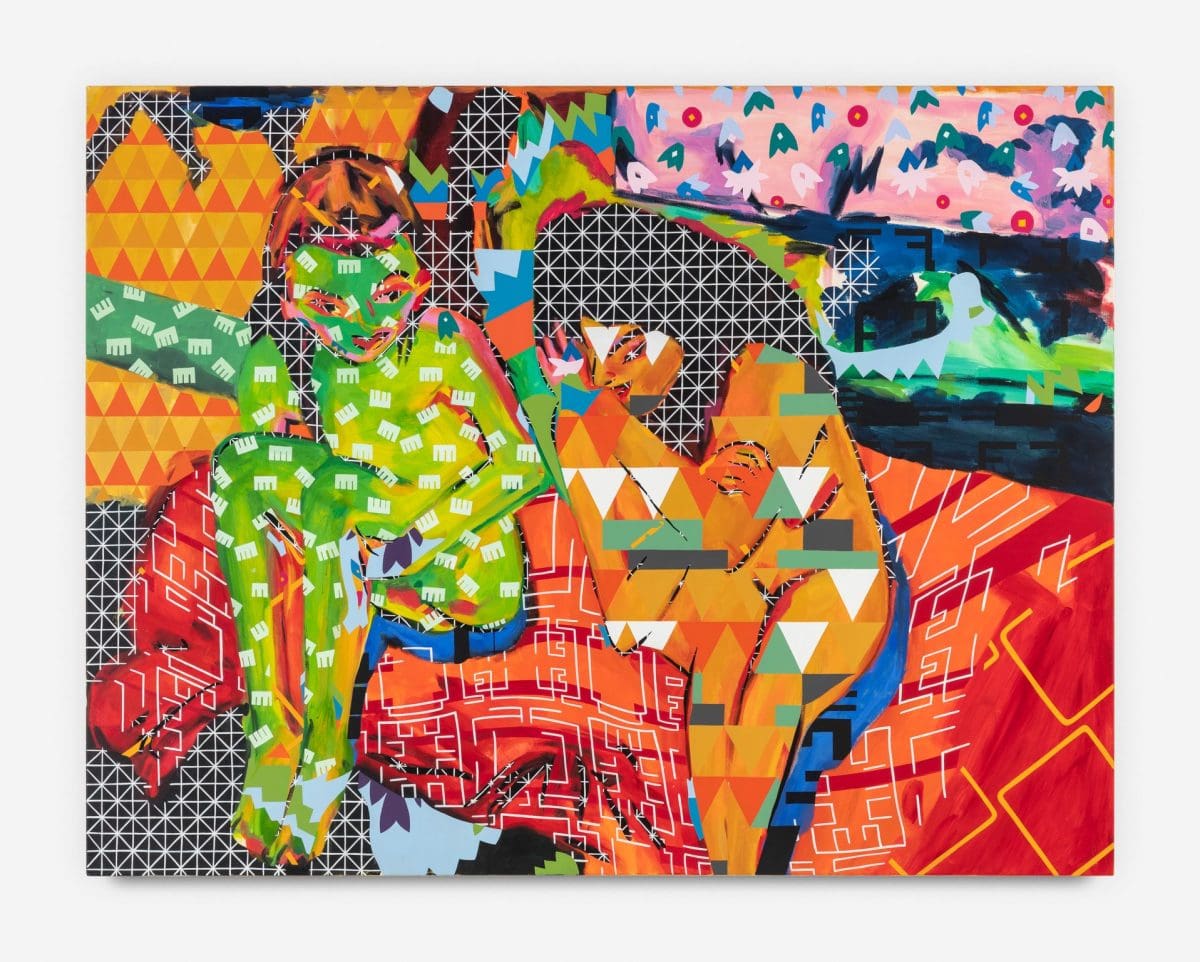

“I have unfinished business with expressionism,” explains Natalya Hughes when speaking about her artistic examination of the 20th-century German painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. The Brisbane-based artist has been studying Kirchner, particularly his paintings depicting two models known as Fränzi and Marzella. “Kirchner is an incredible artist,” says Hughes, “but it’s difficult for me to just gloss over all his work and so, I’ve focused on the most difficult parts.”

“Hughes has become known for her feminist art practice influenced by textiles, costume, and fashion illustration, as well as decorative and ornamental traditions.”

I’m struck by the name of Hughes’s 2022 Sullivan+Strumpf exhibtion, These Girls of the Studio, and I query her about the title: “Are these girls trapped? Why aren’t they considered ‘women’?” Hughes’s answer, despite my awareness of the history of the male gaze, still startles me. “They are quite literally girls… I think the youngest was 13 years old.”

Hughes has become known for her feminist art practice influenced by textiles, costume, and fashion illustration, as well as decorative and ornamental traditions. The artist also deals with how the modernist movement privileged masculine authenticity and authority over femininity and female agency. She creates space for the unnamed to talk back.

Through imagining and then dissembling Kirchner’s artistic process, Hughes can “break it into pieces” and highlight the consequential dismissal of women within art history. “I want to recognise Fränzi and Marzella as actual human beings, two girls who found themselves in an adult studio environment and were being painted over and over.”

Hughes’s work underscores the power imbalance between Fränzi and Marzella and the male artist who portrayed them in highly eroticised ways.

It was Hughes’s “push-pull” fascination with Kirchner’s work that prompted her to investigate. “I remember being attracted to Kirchner’s palette and then being really fascinated by his particular representation of men and women and masculinity and femininity… There are pictures of Kirchner in his studio where he’s completely committed to his art and he surrounded himself in this incredible bohemian life. And just as I’m enjoying, I’m like, wait a second—how old are those girls?”

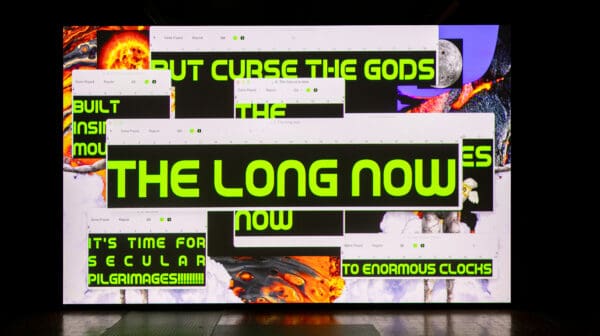

Hughes’s scrutiny into the “stronghold” that male artistic expression has historically occupied is bold and demanding. She credits her resilience in confronting such matters to her experience and research of psychoanalysis—which is apparent in her other current solo exhibition, The Interior.

An Institute of Modern Art touring exhibition, The Interior relates to our internal thoughts and private spaces. Hughes also explains that “in psychoanalysis, ‘interiority’ holds dark secrets, particularly when it comes to the feminine mind and feminine desire”. The exhibition complicates the way women have been both represented and repressed within the history of psychoanalysis.

This has been a massive project, with Hughes creating her own interpretation of Sigmund Freud’s—the founder of psychoanalysis—treatment room. Freud, along with his family, escaped the Nazi regime by fleeing Vienna to London. Now, this consulting room, located in Freud’s apartment up until his death, is known as the Freud Museum London.

“She also thought of the women who may have contributed to creating the textiles and antiquities Freud collected—especially the rug draped over Freud’s iconic couch.”

Hughes became intrigued by this setting and how its furnishings blur private and public spaces. She also thought of the women who may have contributed to creating the textiles and antiquities Freud collected—especially the rug draped over Freud’s iconic couch. This couch was in fact gifted to Freud by a female patient (or analysand) Madame Benvenisti, as she found his previous version too uncomfortable.

In exaggerated and playful ways, Hughes has created colourful rugs embellished with images including rats, snakes and wolves—each work referencing Freud’s famous case studies. Hughes’s uncanny ceramics, mimicking rounded stomachs and breasts, tease out the fraught relationship between Freud’s views on women and the historical relationship between psychoanalysis and feminism. “When I was imagining more dynamic, complicated and possibly provocative spaces for treatment I registered women’s bodies more clearly and not in a negative way, but to be quite fertile, fecund, rich and particularly nourishing.”

Like Hughes’s previous work, this exhibition bares the multifaceted nature of her thinking. “I have faith in the talking cure. That’s also why I wanted to attend to it in this work.” Audiences are invited to recline into Hughes’s sculptural couches, and she hopes for people to be “acutely aware of their own bodies” when doing so.

These Girls of the Studio and The Interior reverberate alongside each other as Hughes invokes and acknowledges the invisibility and anonymity of the girls and women behind the practices of two canonised men. “The representation of women is something that I’ve worked on for as long as I’ve been making art.”

The Interior is a travelling exhibition organised by Institute of Modern Art (IMA), toured by Museums & Galleries Queensland. It is currently on display at Riddoch Arts & Cultural Centre.

The Interior

Riddoch Arts & Cultural Centre

14 June—28 July

This article was originally published in the September/October 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.