Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello’s Glass Acts

Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards 2025 finalist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form.

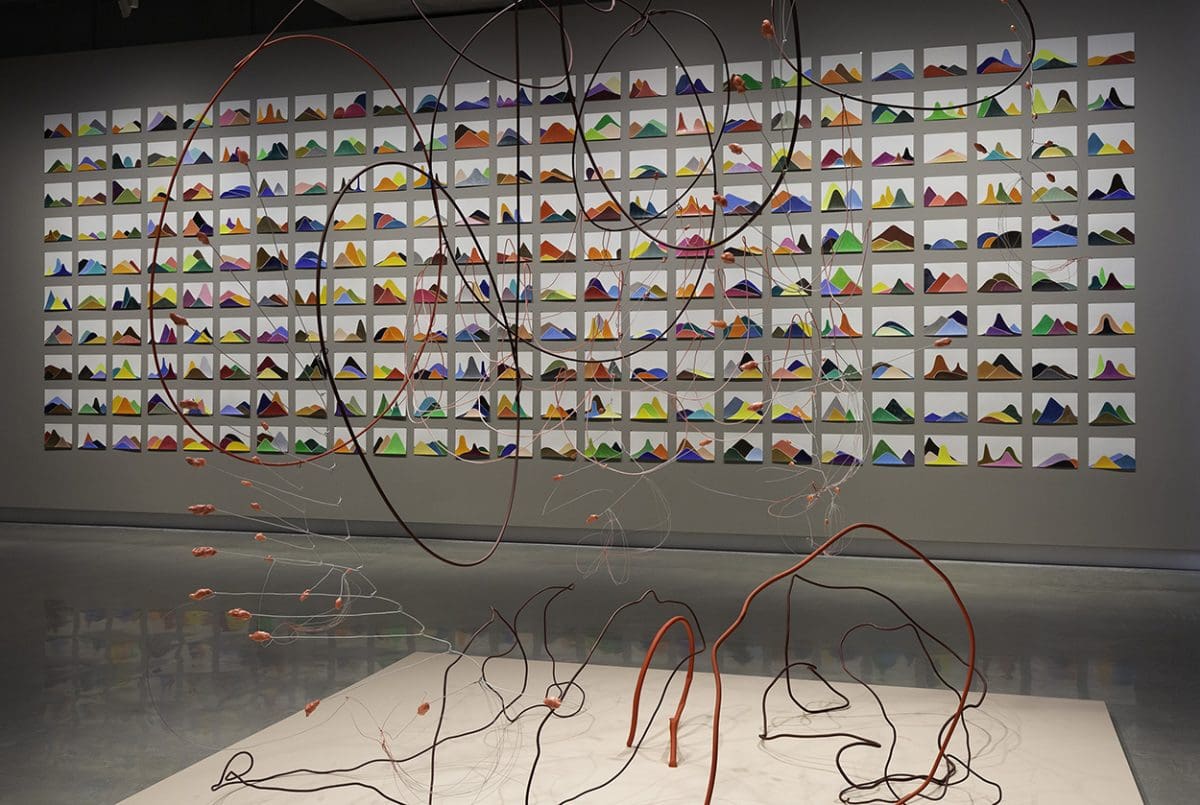

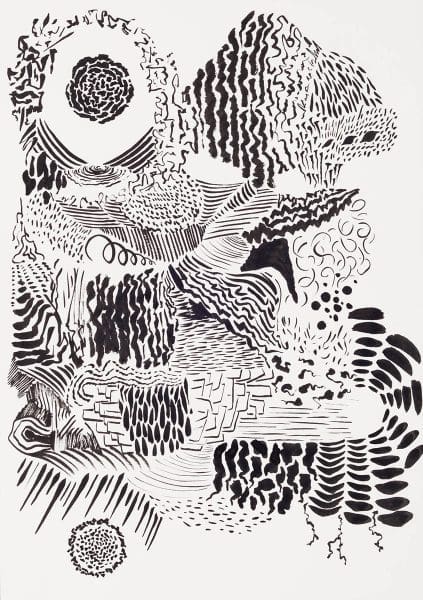

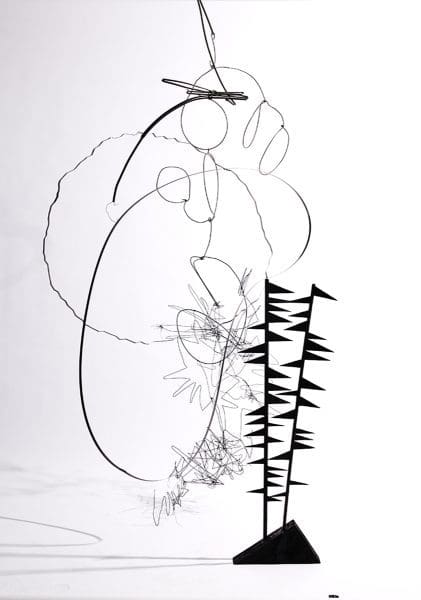

Installation view, The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa, Buxton Contemporary – The University of Melbourne, 7 November 2018 – 17 February 2019. Photography Christian Capurro.

Installation view, The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa, Buxton Contemporary – The University of Melbourne, 7 November 2018 – 17 February 2019. Photography Christian Capurro.

Installation view, The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa, Buxton Contemporary – The University of Melbourne, 7 November 2018 – 17 February 2019. Photography Christian Capurro.

Installation view, The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa, Buxton Contemporary – The University of Melbourne, 7 November 2018 – 17 February 2019. Photography Christian Capurro.

Installation view, The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa, Buxton Contemporary – The University of Melbourne, 7 November 2018 – 17 February 2019. Photography Christian Capurro.

Installation view, The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa, Buxton Contemporary – The University of Melbourne, 7 November 2018 – 17 February 2019. Photography Christian Capurro.

Installation view, The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa, Buxton Contemporary – The University of Melbourne, 7 November 2018 – 17 February 2019. Photography Christian Capurro.

Installation view, The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa, Buxton Contemporary – The University of Melbourne, 7 November 2018 – 17 February 2019. Photography Christian Capurro.

At dusk in Berlin, where he lived for many years, Takehito Koganezawa would watch flocks of birds circling in the distance. From a rooftop, he filmed them. He wondered how they maintained their distance from each other and how each bird knew how to fly in concert with its fellow travellers. While he knew there was no leader in a flock, he was mesmerised by their swooping.

Motion has always interested Koganezawa. Though he’s long been fascinated by the action painters of the 1960s and sees some of his work as something of a homage to them, his own interest has steadfastly remained with drawing: he hasn’t the skill, he says, for painting. “I try sometimes on the canvas, by myself,” he says. “It never works. Really awful.”

Gaze, then, at his extraordinary video and drawing- based works, which have a propensity to entice you into their reveries. While he has been making the moving- image works for many years, he never repeats himself, his mind skipping to a new subject and method – yet he retains a consistently poetic tone.

For a new joint exhibition, The Garden of Forking Paths, Koganezawa was approached by two curators, Japan’s Shihoko Iida and Buxton Contemporary’s Melissa Keys, interested in teaming him with Australian artist Mira Gojak. It was explained that they wouldn’t be making work together or collaborating – it was simply felt that there were enough “points of connection and divergence” in their respective oeuvres to form an interesting exhibition.

When Koganezawa started looking into Gojak’s work, he found a deep connection in her commitment to drawing, even though much of her work ended up being sculptural – whereas his own tended to moving-image forms. “When I saw it, there were very familiar feelings, even though the work is totally different,” he says. While Gojak’s interest in animals and the natural sciences was strongly evident, his own evoked sport, bodies and motion. “It is a good combination,” he says. “Sometimes a two-person show is more like martial arts. This has been very peaceful.”

While both artists show alongside each other, they remain distinct in the generous, unusually shaped rooms of Melbourne’s Buxton Contemporary. Koganezawa describes it as being part-retrospective, part-experiment for both of them, with recent works included.

She took him there and he found it to be as atmospheric as he’d imagined. Then, it was straight into making work at a University of Melbourne residential studio in Carlton. There, he began creating a series of motion-themed videos filmed, oddly, inside a wok. The swirling coloured liquids he shot are almost monumental in their dramatic, lava-like formations.

He also started making flip books – cascades of them are stacked on his desk and as he flicks the pages to display his creations, again, it is like some form of hypnotism. These are unlike any flip books most of us have encountered: their hand-drawn patterns are fastidiously inscribed in such a clever way that as the pages fly by it is as if a three-dimensional pattern is manifesting in the air between the pages.

He describes one of these as being about “setting the butterfly free”. “It looks just like a book but when you flip it, the world just happens. And speed controls how you experience it. It is not like showing only the butterfly – it comes from the book, into the air.”

It is this idea of motion that most consistently connects Koganezawa’s work. Among these are videos whose content sounds facile but, when viewed, have a poetic resonance: aeroplane contrails running in different directions; dust particles dancing through the air; fragments of neon lights flicking in the evening light; headlights blurred magically during peak hour, and of course those enigmatic flocks of careening birds in flight.

Koganezawa says our responses to art are always subject to timeframes. In front of a painting, for example, we can let our minds receive the visual information and respond at our own leisure. In front of a moving image, however, the artist has some control: the speed of the work acts as a sort of guide, pulling our eyes and minds along at a certain velocity. This, he argues, determines how we might respond emotionally and intellectually.

“Because I see the world is moving, the world is floating. Life is in the flow. But people like to set up in a place and to see [the world] from a fixed point and think about it. Without motion, you can think at your own speed. But the speed of your consciousness or the velocity of your thoughts is totally controlled by motion.”

He thinks in particular of his video of slow-moving traffic in Sao Paolo, Brazil. “The traffic there is terrible,” he says. “They maybe failed to make some infrastructure: every evening it is gridlocked. If you are in a car, it is stressful; but if you are watching from the bridge, it is such a nice sight, slowly coming down the road.” With the lens softly focused, the lights of oncoming cars blur into glorious, fuzzy glowing orbs, gently gliding through time and space. It’s beautiful.

The Garden of Forking Paths: Mira Gojak and Takehito Koganezawa

Buxton Contemporary

7 November 2018 – 17 February 2019

This article was originally published in the January/February 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.

Read Varia Karipoff’s previous interview with Mira Gojak here.