Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

The explosion of the true crime genre in recent years came with the discovery that its fans are overwhelmingly women. Theories abound, but a popular one is that women engage with true crime because, more often than not, they are the victims—and knowledge is power. What may look like morbid curiosity is an inherent need to know one’s enemy.

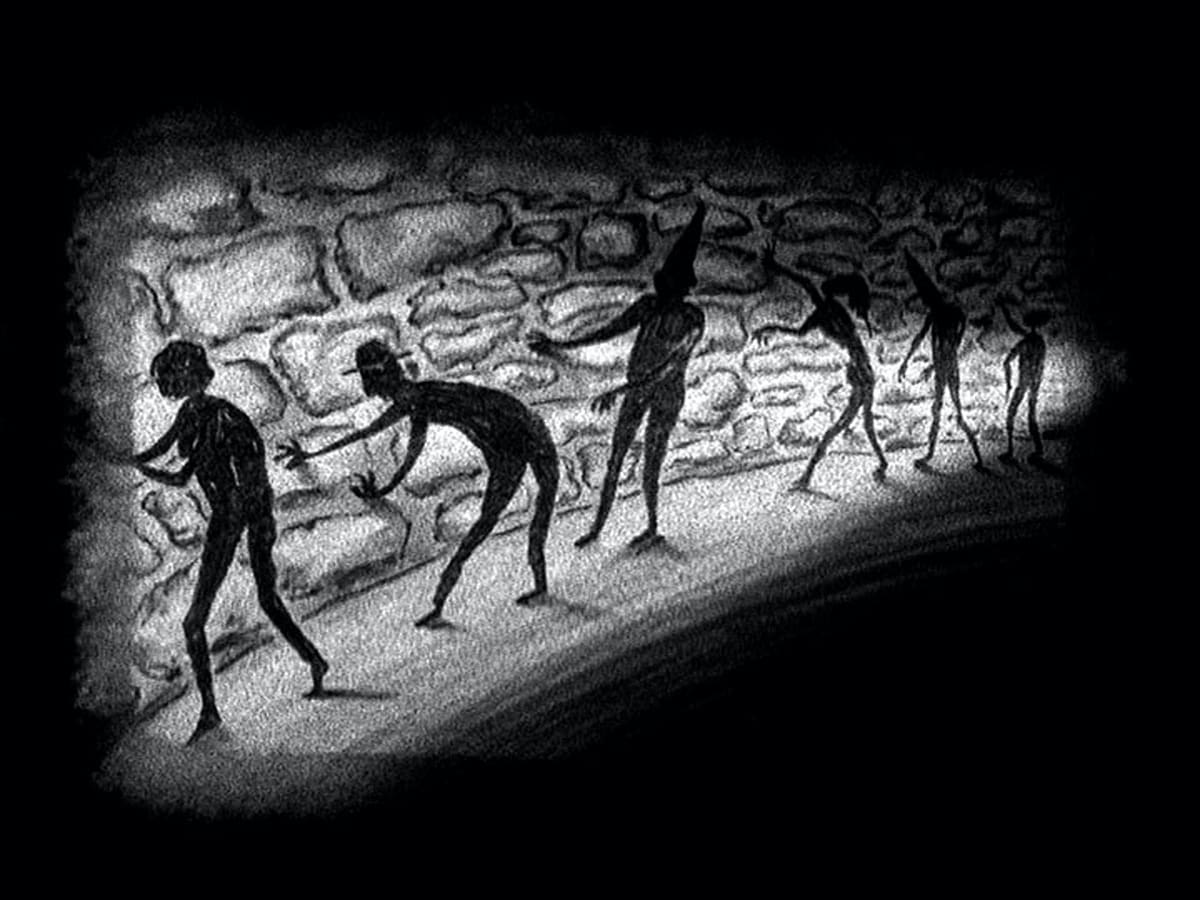

The same can be said of horror, where women take centre stage as the victim, the terrorised, even the villain. Horror is where the marginalised see themselves, if not as heroes, then at least as lead characters. It’s for the outsiders, the repressed, those whose otherness has so often hurt them—but in horror, it hurts back.

This is the focus of From the other side, the new summer exhibition at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA). Curators Elyse Goldfinch and Jessica Clark have delved into a rich history of horror in art that few of us knew was there, bringing together 19 practitioners who explore the abject and transgressive in ways that excite and terrify.

“I was looking for the voices and perspectives that, in this current moment, felt most relevant,” says Goldfinch. “Particularly looking at First Nations perspectives, feminist perspectives, people of colour. That informed a lot of the research, and became how we decided to find the 19 artists.”

From international names—Louise Bourgeois, Marianna Simnett, Suzan Pitt, Minyoung Kim, Lonnie Hutchinson—to a diverse array of local artists, both established and up-and-coming, all those represented are women or gender-diverse, a considered step towards reclaiming the genre for those it so often looks to exploit. This is also why they wanted to incorporate as much Indigenous representation as possible.

“I had this revelation that horror is the everyday,” says Clark. “I’m coming to it from a First Nations perspective, where there is horror in this place, in daily life with the current political climate. Not to mention the historical horrors of colonial violence that are just embedded everywhere in this place and space.”

Included in the show is a representation of Tracey Moffatt’s A Haunting. “Physically, it’s in situ in Armatree, an hour and a bit out of Dubbo on the Castlereagh Highway,” explains Clark. “So you can actually drive to this site where there is nothing around for miles. Tracey has lit up this old house, it lights up every night at dusk and kind of pulsates with this red light. The eeriness, for me, draws in all of these connotations, like what violence may have unfolded in the landscape around it? Or within that domestic space? What happened in that house?”

A Haunting will be shown in the form of projection, paired with an atmospheric soundscape, crickets and all. “It’s incredibly unnerving, but equally beautiful.”

A significant influence on the show is the work of Australian academic Barbara Creed, whose 1993 book The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis provided a framework for thinking about the depictions of women as monsters in horror. She interrogates the fact that the monstrous part of a woman is often her body—after all, many women’s bodies bleed monthly and give birth, events that are inherently gory.

Berlin-based artist Marianna Simnett interrogates themes of bodily horror in her work. Her video installation at last year’s Venice Biennale, The Severed Tail, used the practice of tail-docking to explore the fetishistic and animalistic side of the human body. Her inclusion in From the other side is a video work from 2014 called The Udder.

“It’s a really beautiful, provocative work following this young girl growing up on a dairy farm,” says Goldfinch. “Her father, the farmer, talks about the potential threat of mastitis among the cow population. Meanwhile, she is about to come of age and is dealing with the potential threat of what that means to her body, her sexuality. The film deals with horror in a really indirect way; it’s about the possibility of threat rather than something violent actually happening.”

While horror as a genre has had something of a renaissance in film and literature (one only needs to look at the critical success of Jordan Peele’s Get Out, and closer to home, films like The Babadook and Relic), horror in art is not a theme we often see explored curatorially. That’s not to say it doesn’t exist, which is a point Goldfinch wants to highlight: “It was really important to have new commissions with existing and historical precedents as well, [to show that] there has been a long history of this work.”

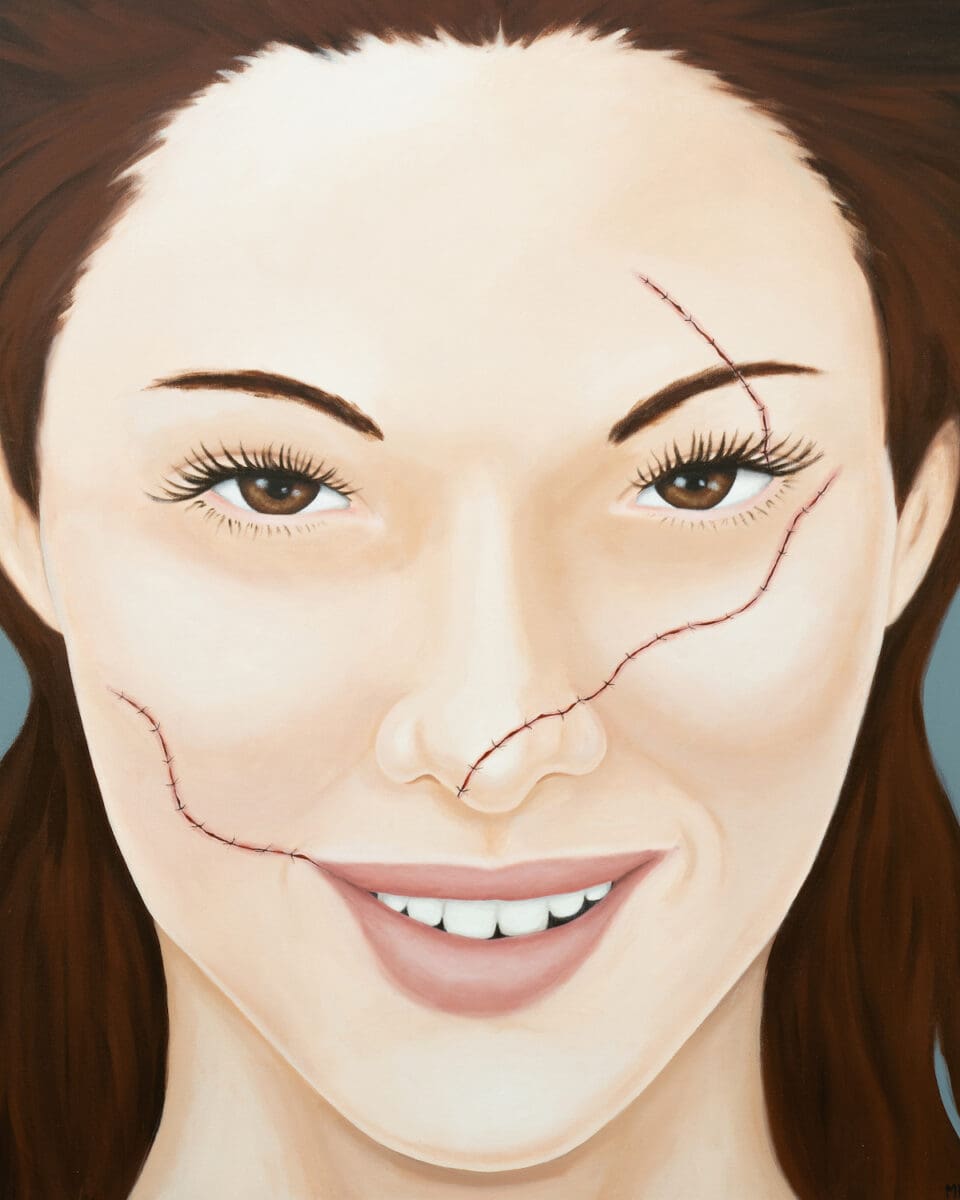

Take Maria Kozic’s Calendar Girls series from 1999. Each of the 12 large-scale portraits depict a different model: beautiful, smiling, wounded, and disfigured. Something terrible has happened to them. Miss March bears scars from an attack by a man she rejected. But alongside her scars is a knowing, almost malevolent smile. I’d be willing to bet Miss March got her revenge, and I’d sure as hell watch a movie made about her.

From the other side

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA)

9 December—3 March 2024