Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

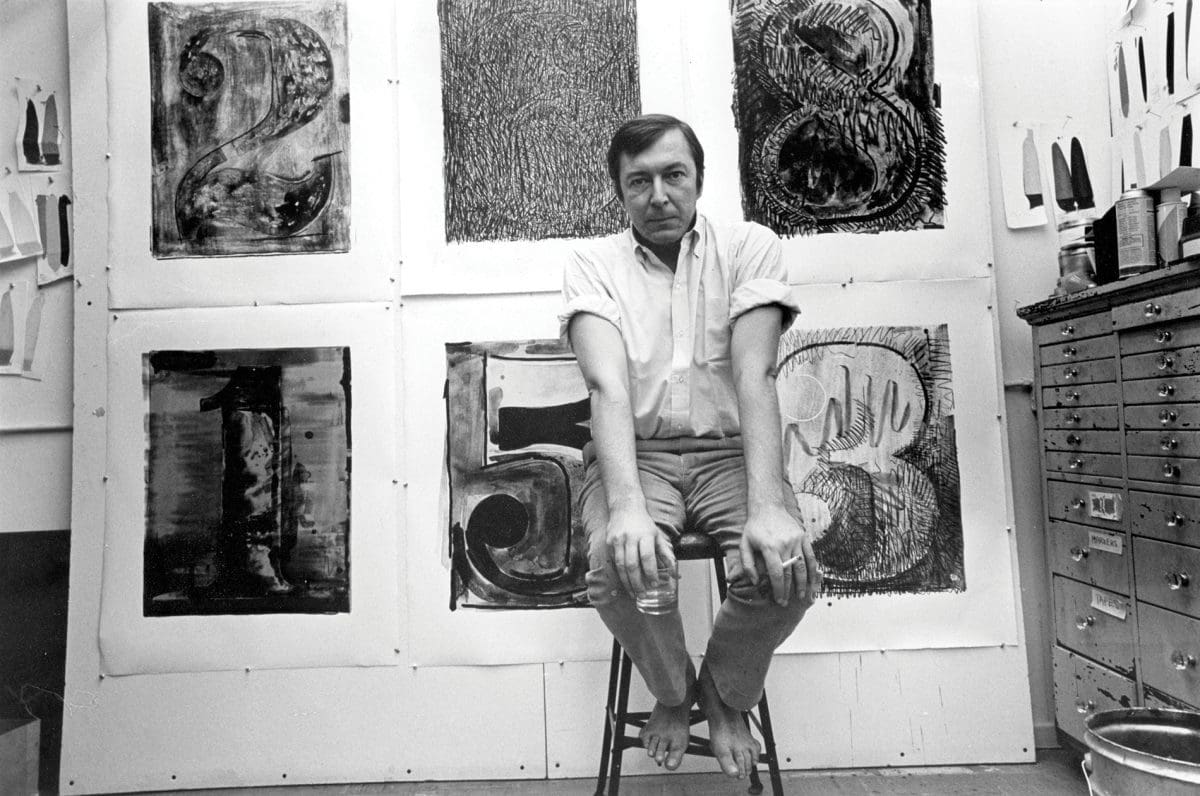

Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg met in 1954. Rauschenberg was five years older than Johns, but they had things in common. They were both born in the conservative southern states of America, Johns in Georgia and Rauschenberg in Texas. Both had served in the US Armed Forces: Rauschenberg in the Navy in World War II and Johns in the Special Forces during the Korean War. And both were gay men, although arguably in the closet, and started a relationship soon after meeting. Indeed, needing money early in their careers, they worked together as window dressers, as Andy Warhol would also later do, under the collective name Matson Jones Custom Display, fearing the potential damage to their artistic reputations.

It is often suggested that Johns got his ideas from Rauschenberg, who had already been creating a series of ground-breaking performance pieces at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina from the late 1940s and was showing at the prestigious Betty Parsons Gallery. Rauschenberg apparently got jealous of Johns’s artistic success, which overshadowed his own, and they broke up, again apparently acrimoniously in the early 1960s, although there is a great photo of the two of them laughing together at the workshop run by American master printer Kenneth Tyler in 1980, at the very height of their artistic acclaim and success.

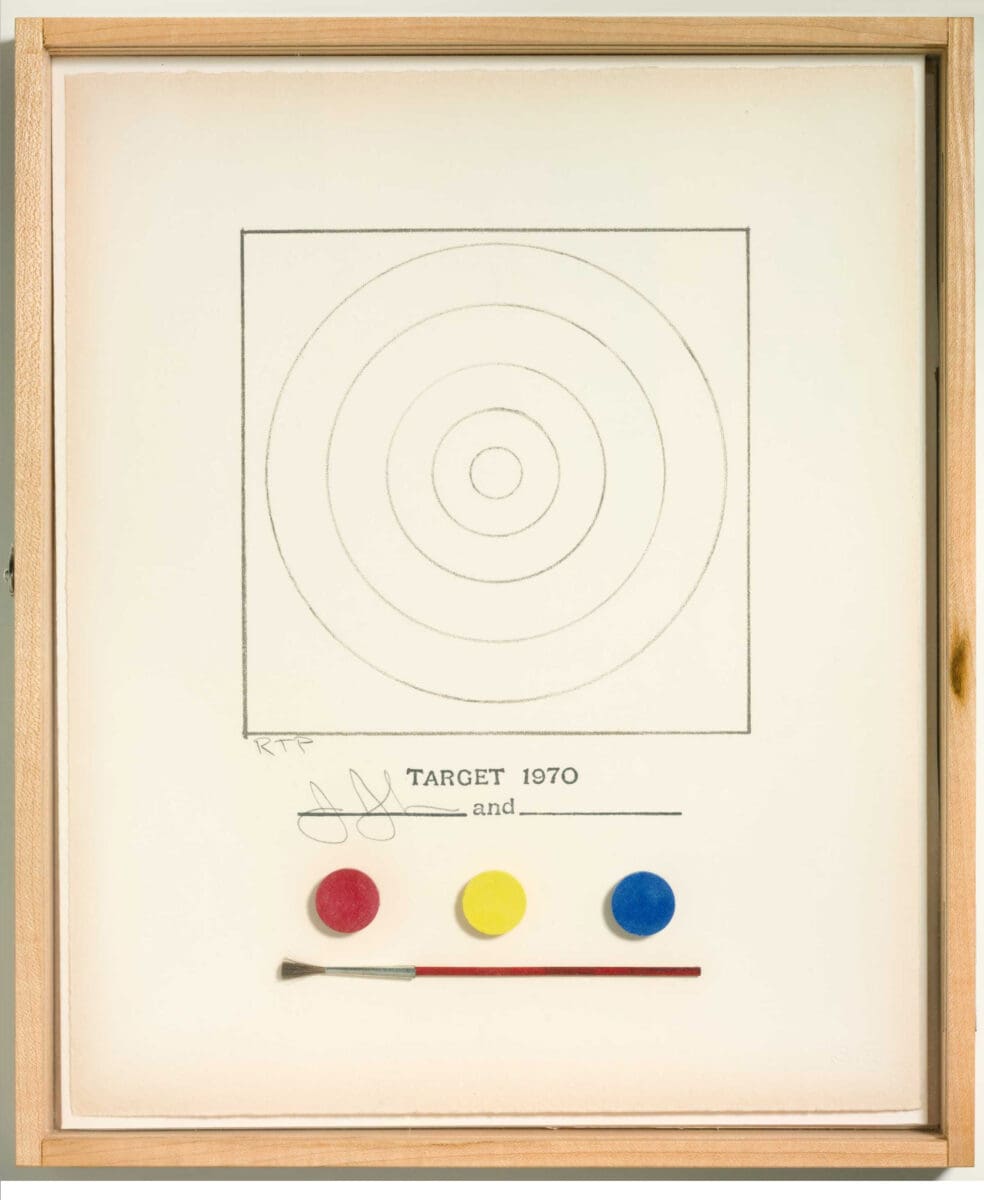

Now the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) is putting on Rauschenberg and Johns: Significant Others, drawing largely on the extraordinary archive of prints Tyler made for both artists, which he donated to the NGA, as well as a selection of works by Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray and René Magritte. Of course, with its title—which alludes to Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle De Courtivron’s well-known Significant Others: Creativity and Intimate Partnership, which recounts the stories of various famous artistic couples, needless to say mostly great male creators and their female muses—the show is first and foremost about the relationship between Johns and Rauschenberg. Indeed, the show cannot but remind us of the National Gallery of Victoria’s current Queer: Stories from the NGV Collection, which actually includes Johns’s Target, 1967, and Rauschenberg’s Pledge, 1968, hanging next to each other.

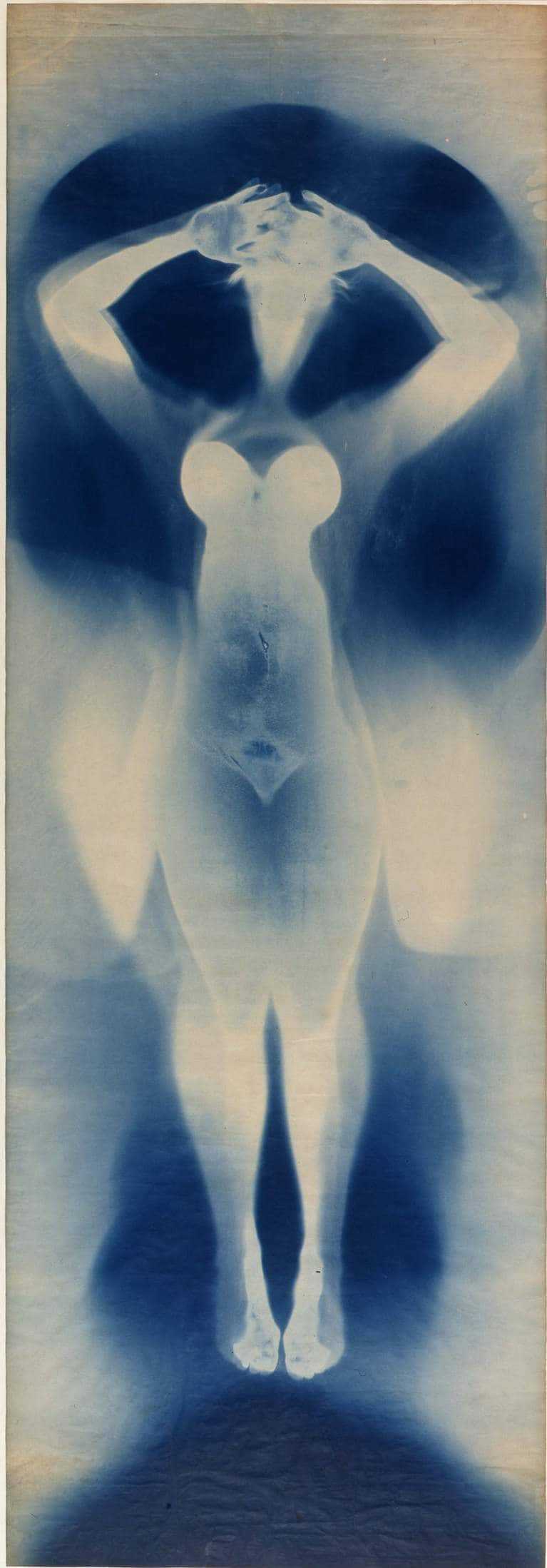

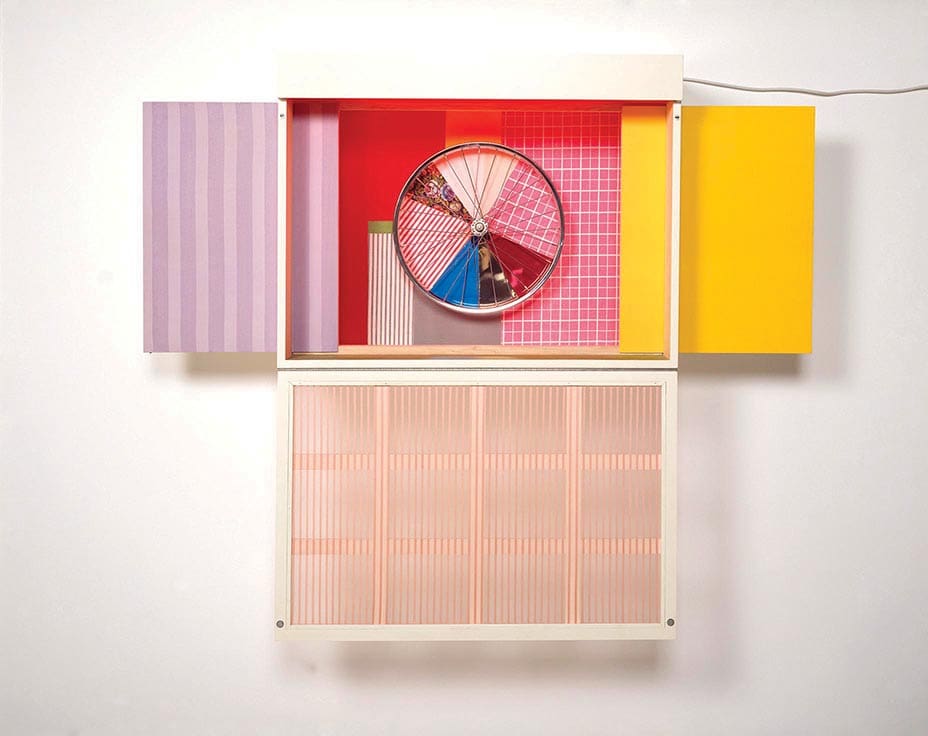

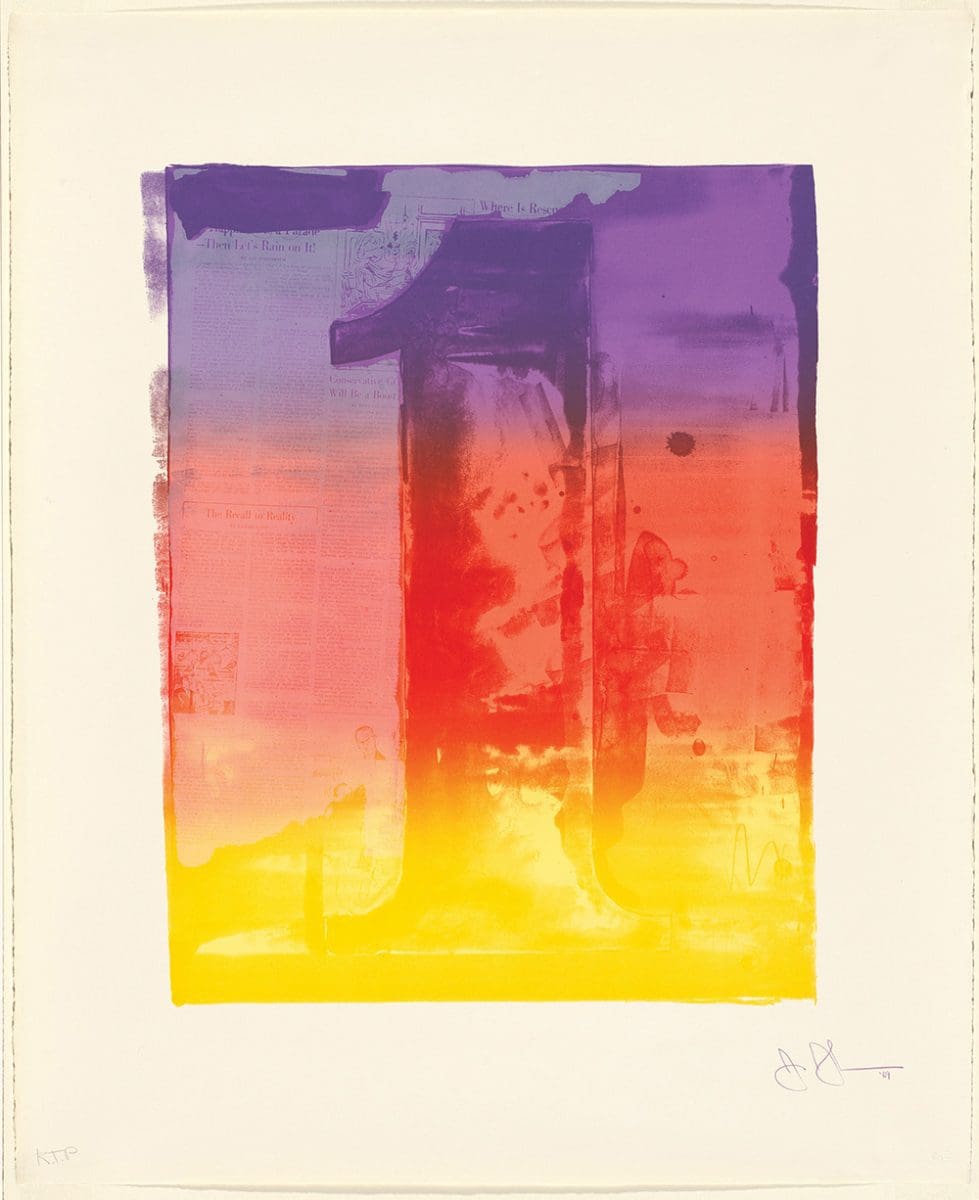

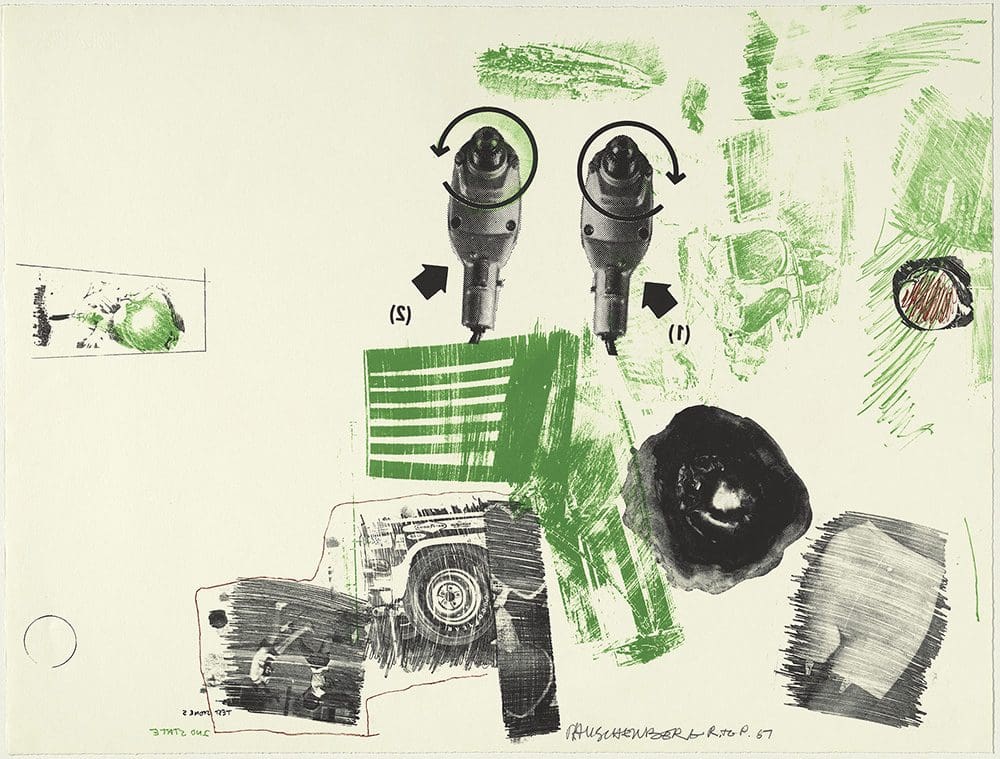

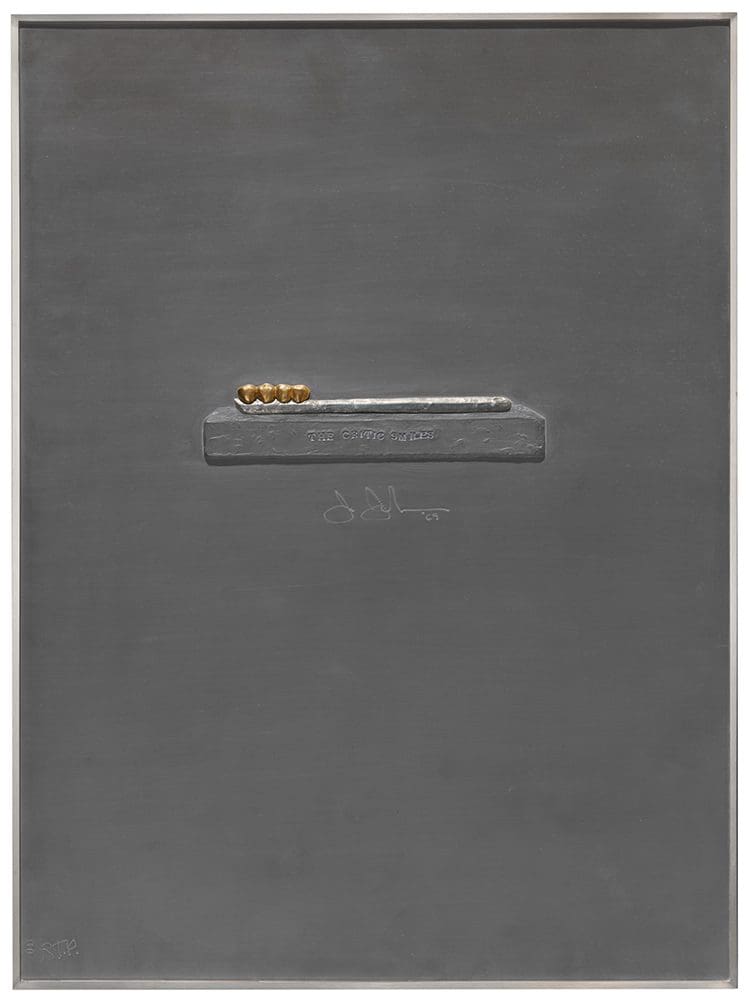

For its part, Significant Others includes such Tyler prints as Johns’s The Critic Smiles, 1969, which features a weird lead toothpaste; Bent Blue, 1971, his pisstake of Picasso’s Synthetic Cubism; and a full set of his Coloured Numerals, 1969, running all the way from 0 to 9. The show also includes two of Rauschenberg’s late Publicon “combines”, 1978, which are an even more complex feat of manufaturing by Tyler, although it is a pity we don’t get one of the early ones like Gift from Apollo, 1959, which seems somehow more authentic in its grime and dirtiness.

What’s the big revolution started by Johns and Rauschenberg? Why are they both such important, indeed turning point, artists of the 20th century? Take, for example, Johns’s Flag, 1954, made the year he met Rauschenberg and arguably the work for which he is best known. It’s simply a reproduction of the classic stars and stripes over a surface made up of shredded newspaper covered with white encaustic paint. The flag sits evenly on its plywood backing without remainder, as though it were just a flag we were looking at.

The big question raised is whether this is any more a painting or simply an object in the world. Decisively, it rejects someone like Clement Greenberg’s demand that painting make the medium of painting as its subject matter, somehow sublimate its physical constituents and turn them into the subject of the work. That is, as opposed to the Abstract Expressionism of the time, Johns’s Flag just is its everyday reality—that’s the black print of the newspaper we see running beneath it—and it doesn’t take place anywhere but in the here and now.

Flag is not just a refusal of the dominant painterly style of the time but of art altogether. It’s not aesthetic, it doesn’t appear creative, and the person who made it is not any special kind of person. After Flag, “art” can go either one of two ways: it can be aesthetic or anti-aesthetic, it can be a work of art or a thing in its world. We are still puzzling out the consequences of Johns’s intervention—yes, as the NGA reminds us, there was already Duchamp, but Duchamp wouldn’t be who he was without Johns and Rauschenberg.

Every time an artist makes a work of art “about” contemporary issues and someone complains about that, saying that’s not what art should be, we go back to 1954 and Flag. It’s maybe ironic that we’re still thinking about the end of art in an art gallery, but it is this dilemma itself that is art today. And, yes, the critic might smile at all of this, as though they know better, but the joke is also on them.

Rauschenberg and Johns: Significant Others

Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg

Museum of Art and Culture yapang Lake Macquarie, NSW

9 Dec 2023 – 4 Feb 2024

This article was originally published in the May/June 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.