Yhonnie Scarce is a Kokatha and Nukunu artist widely recognised for making blown glass in black. Often using the form of yams to represent the bodies of Aboriginal peoples, she has earned critical acclaim for her research in nuclear testing and its ongoing impact on First Nations communities. As a fan of her work, I was excited to hear that the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA) is hosting a retrospective of her oeuvre, The Light of Day.

It will witness the evolution of Scarce’s work, which often unpacks harrowing stories of nuclear colonialism with astonishing beauty.

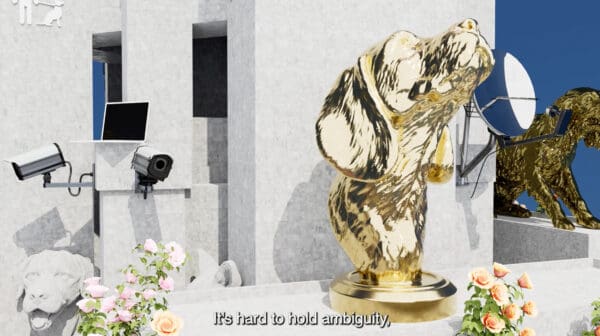

Diego Ramirez: The Light of Day gathers over 30 of your artworks, with nuclear colonisation being a prominent theme, among other research areas. Could you please tell me about the glass nuclear cloud works that AGWA sourced for your retrospective?

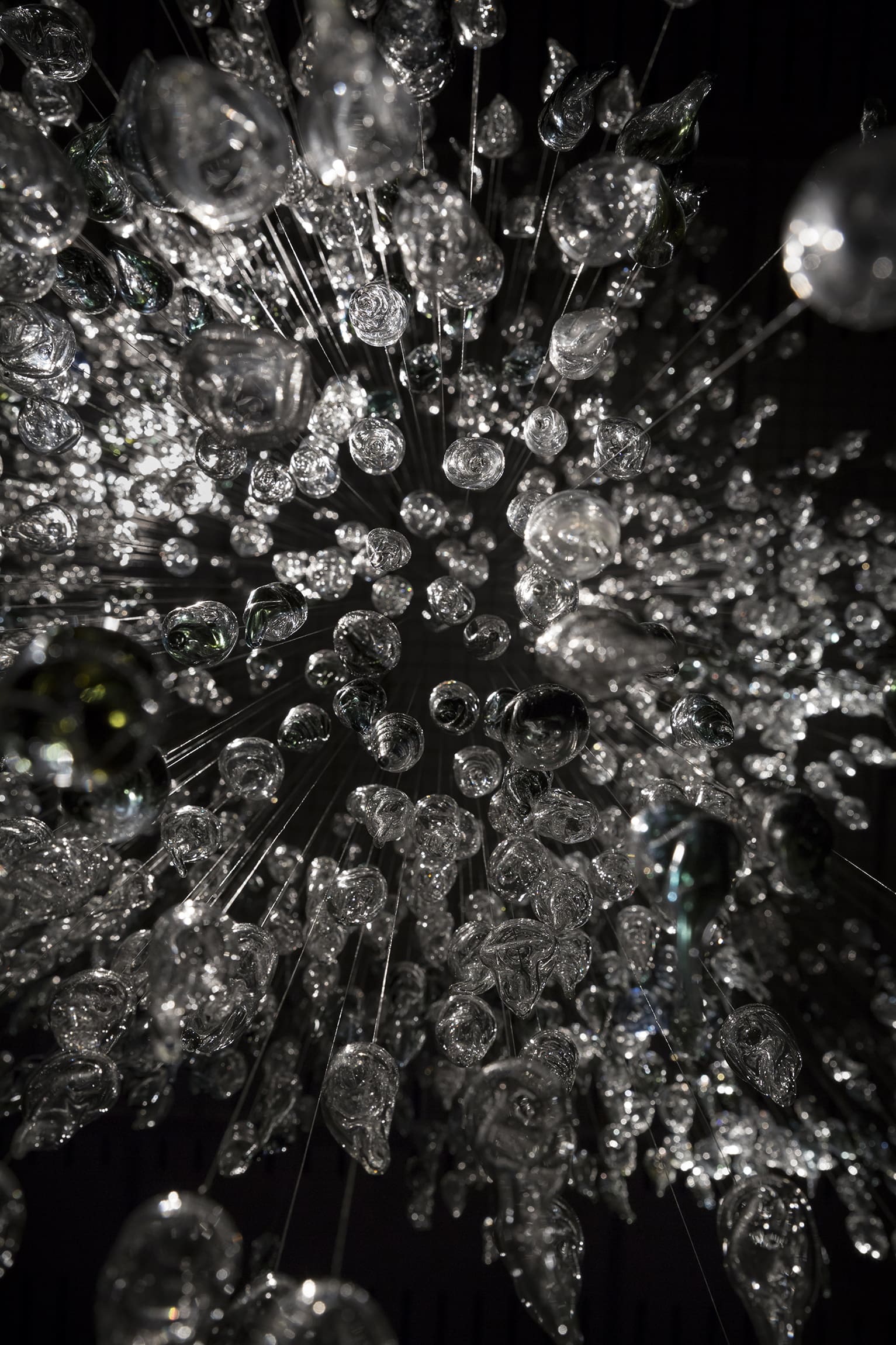

Yhonnie Scarce: At the moment there are six nuclear clouds, and AGWA will show three of them. Thunder Raining Poison, 2015, the first cloud I ever created for the Art Galley of South Australia will be there, as well as Death Zephyr, 2017, created for The National 1, and Cloud Chamber, 2020, made during the pandemic for TarraWarra Museum of Art. They’re all large clouds. The works deal with nuclear disaster, genocide, family history, and the colonisation of Aboriginal people, including their removal and incarceration, as well as the scientific testing that was inflicted upon them.

There are over 30 works in the show that begin with family, to explore broader issues of nuclear colonisation, and how it has affected my family as well as my Country.

DR: Your signature work is made with glassblowing, and I was thinking about the relationship between breath and voice, as means to give a voice to these stories.

YS: I’ve often said that creating each glass piece is like recreating, or reviving, people who were lost. And because it’s such a physical activity too, there’s this intimacy that I build with each piece. It’s cathartic because it helps me create a sense of closeness with my ancestors and the people that I’m representing in the work. So, I always try to avoid having too much control over the creation of the work. Breath is obviously very important, as it is how we create blown glass. My work is part of me and because I use my breath to make it, every object becomes an extension of myself. So, every time I create something I experience the mutation of the glass, or notice how I begin to mutate with the work.

DR: Mutual mutation… it’s always interesting to see these intact glass pieces that are unbroken in the context of an explosion, which creates a beautiful tension.

YS: This is most relevant with the nuclear tests in Maralinga, South Australia, because there’s glass out there, in one of the bomb sites. So, my work looks at strength in Country while considering the effects of heat and poison. The bomb clouds that I create have this sense of destruction but also a sense of duty because Aboriginal people are in the clouds.

DR: What is the research process like when looking at a nuclear site, like Maralinga in South Australia?

YS: I do a lot of field work on Country to visit Woomera, my birthplace, and Maralinga, to be around extended family out there. When making large works in particular, I need to be in a quiet place, like the desert, which is silent. There’s something going on out there but it’s always hard to describe it. That’s where I’m able to have the space to work and feel what it may have been like to be out there, like my ancestors. There’s a lot of travel and a lot of talking to people, especially when I’m making work about South Australia and my family.

DR: A lot of your work also takes the form of yams, can you talk through that?

YS: Yams are very present in my work because I use them quite often to represent deceased Aboriginal people. So, when I’m making work about genocide or atomic clouds, they’re representing the spirits or the bodies of Aboriginal people. Bush bananas also seem to be reappearing quite a lot recently, as I use them in relation to the desecration of bodies. And the bush palms are getting bigger and bigger, increasing in size to represent the Aboriginal babies that were affected during nuclear testing. It depends on the work and the story behind it, but there are always multiple objects, never one on its own.

DR: I’m looking at Cloud Chamber, one of the nuclear clouds, and my first reading is uprooting: yams leaving the earth. But then I notice they’re also drops, falling from the sky in the broader shape of a nuclear cloud. It is such a masterful command of sculptural objects, that is always evident in your work, as it seamlessly holds multiple connotations.

YS: Despite the stories behind these particular works, I do enjoy the process of creating them. I always use photographic evidence to recreate the atomic clouds in a gallery space. And as you said, the yams are taken up into the sky, but they are returning as well. They’re quite mobile in a ritual sense.

DR: The amount of labour is almost a material itself because it’s such a demanding practice.

YS: I can’t speak for every glassblower but for me, I have to go through a process in order to prepare myself for four hours of glassblowing. I think about the works that I’m creating the whole time that I’m making them, the stories behind them. And then see what happens, see how many yams I can create in four hours. I don’t necessarily like bright colours because I don’t think it is appropriate for these kinds of stories.

DR: You’ve travelled overseas to visit nuclear testing sites, could you please tell me how it has enriched your understanding of national sites?

YS: I went to Chernobyl, Fukushima and Hiroshima. It is similar in a way, as these places share a nuclear trauma that has been covered up, to hide how detrimental the effects have been. I like finding out information about other sites like Marshall Islands, where the USA conducted nuclear tests. Visiting these places one realises how scary nuclear energy can be, and it’s not clean—they don’t know how to control it. Unfortunately, it is all over the world.

DR: The act of blowing glass speaks to this idea, as it provides the means to control or shape material, but also carry the remnants of invisible energy.

YS: A nuclear bomb, if you see footage of a cloud, is something else. It is brighter than the sun, but radiation poisoning is invisible, it doesn’t make itself known until it begins to affect your body. The cloud appears but disappears eventually, whereas the poison remains, even though it is unseen.

DR: That is what heat does to glass too, in the sense that it inflicts a mutation upon a body, right?

YS: In Chernobyl, animals were being born with multiple limbs and in Fukushima, they are talking about finding local life with several deformities. In Maralinga, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people were affected by testing too. That’s why Woomera is also very important for me because the cemetery is full of children who were born with issues during that period. It’s an ongoing problem in the Aboriginal community because kids are still being born blind, with lung and spinal issues as well as developing cancer quite early.

DR: That’s truly awful… What are the specific Australian sites that have influenced the works in the show?

YS: Koonibba Mission, where my grandfather was born, is a place that I visit quite frequently because he is buried there and it is part of my history, unfortunately. So, I return quite a bit. I also return to Point Pearce Mission because that’s where the history of my grandmother unfolded. My birthplace Woomera is really prominent in my research, that’s where my interest in the militarisation of Country as another form of colonisation originates. There are also a number of massacre sites, that I return to quietly, I don’t talk about it much because it’s quite personal. I also return to Maralinga, of course. But you have to limit your time at an old nuclear test site, as you can’t hang around there for too long.

DR: What does your retrospective mean to you?

YS: It hasn’t fully kicked in yet. For me it’s really exciting to have so many works on display, all at once together. It is the first time that three clouds are shown together, so for me it’s a great honour to have this happen. Also, to look at the archive of my work and realise how much has been done because I’m so used to working on new projects, it’s great to revisit and remember older works.

The Light of Day

Yhonnie Scarce

Art Gallery of Western Australia (Perth/Boorloo)

On now—19 May

This article was originally published in the March/April 2024 print edition of Art Guide Australia.