From her first studio in the bushland artist community of Wedderburn, NSW, to a recent

residency at the Pha Tad Ke Botanical Garden in Luang Prabang, Laos, Savanhdary

Vongpoothorn has always practiced in proximity to nature.

At Pha Tad Ke, Vongpoothorn researched the ethnobotany of the garden’s trees, seeking to understand the relationship between the Lao people and the medicinal, spiritual and cultural uses for plants. This investigation stemmed from an interest in anthropocosmism—the interconnectedness of humans and the cosmos.

Drawing on the influences of Theravāda Buddhism, Hinduism, textiles, language and Western modernism, Vongpoothorn’s multidisciplinary works are transcendent, incorporating elements of painting, drawing, sculpture and embroidery.

Ahead of her solo exhibition at Niagara Galleries, Vongpoothorn contemplates the ideas sprouted during her residency, and how they transformed once she returned to her Canberra studio.

Place

Savanhdary Vongpoothorn: When I took up a studio residency at Pha Tad Ke, the only botanical garden in Laos, I wanted to explore the ethnobotany of the banyan tree. The tree features in the 14th century Lao retelling of the Ramayana, Phra Lak Phra Lam / Rama Jataka. A magical banyan tree turns Rama and his wife into monkeys after they eat its fruit.

I’ve been inspired by the Rama Jataka since 2013, so the magical banyan tree already held space in my mind and my dreams before taking up this residency.

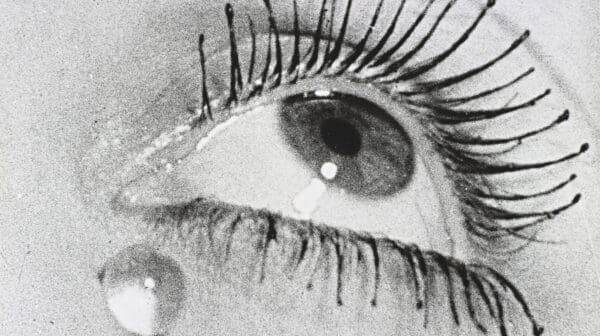

When I arrived in the garden, the first thing I did was seek out the banyan tree at dusk. It was spooky. I had come to take some ink rubbings of this tree—I have done similar rubbings for past projects—but as soon as I laid eyes on the banyan tree, I had immediate shivers of fear.

It wasn’t a personal fear, it was a cosmic fear, a kind of primal reaction to this tree. It was heightened by my knowledge of the history of the garden and where it is headed, now that it is on the market to be sold to developers. I knew then and there that the tree could not be tampered with.

I spent three weeks of bliss in this garden. I didn’t have to cook and had total freedom. All I had to do was stay in the studio and work. The last thing I saw when I went to bed at night and the first thing I saw when I woke up early in the morning was my work. I was working around the clock. The garden became a poetic space for me to be creative.

The world is my studio. Every time I travel, I’m always looking for primal interests. I guess that’s part of being an artist; you always seek experiences that are poetic. The studio is a transformational space, and my ideas transform wherever I am.

Process

Savanhdary Vongpoothorn: After this experience with the banyan tree, I came across the kapok tree, nicknamed the devil tree because it is covered in large, pointed thorns. I wondered what the ethnobotanic significance of this tree was. A local told me to go to the temple to learn more about the story of the tree, filling me with excitement about the mythology behind it.

The murals of the kapok tree in the temple tell the story of the monk Phra Malai, who obtains supernatural powers and is subsequently able to visit heaven and hell. He grants mercy to the damned who implore him to warn their relatives of the horrors of hell, and how to escape it by obtaining merit through following the Buddhist precepts.

The story is represented in temple murals throughout Luang Prabang as a warning to people. But for me, the kapok tree isn’t just the devil tree. It’s a tree that offered me this beautiful and spiritually fulfilling artistic process.

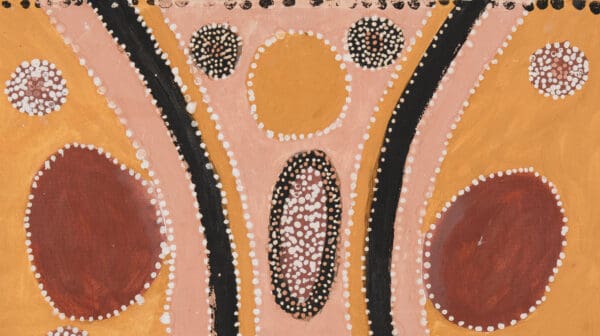

I used local handmade Saa mulberry paper and drew on it with pastels. After fixing the drawing, I wet the paper and pressed it onto the tree, so that the thorns embossed and perforated the paper. The paper is left to dry before peeling it off the thorny trunk. The paper is thin but strong and wetting it before embossing gives a beautiful colour saturation which I love.

The imagery I used in the Tree series was inspired by the ikat textiles of the Lao Mien ethnic group. It’s a symbol of a bridge between ancestral and human worlds, which is where the exhibition title, A Bridge Between Worlds, comes from.

Projects

Savanhdary Vongpoothorn: I started using beeswax because I wanted to learn a Hmong textile technique. There is a special tool, unique to the Hmong, that is used to draw geometric designs in wax onto hemp fabric before it is dyed. In Laos, we use beeswax for religious ceremonies to connect with the spiritual realm. Beeswax is a symbol of light, purity and personal transformation.

The Palm Leaves series was inspired by the palm tree section of the garden. I was thinking about the photosynthesis of plants and the porous boundaries between self and nature. Applying beeswax using the Hmong tool on top of my pastel drawings of palm leaves has created beautiful transparencies that give

the illusion of wetness.

Another thing I’m working on is part of a much bigger project—using the same embossed paper sewn together into a large-scale work containing text written in wax. On this larger scale these works remind me of tapa, a barkcloth made in the islands of the Pacific Ocean. I’m always fascinated by language, particularly religious script, the way languages migrate from place to place, form and re-form, merge and integrate. I think it has a lot to do with my feelings about Lao, my original language.

I want to discover more about the ethnobotany of Australian trees in botanic gardens. I am also planning more visits to the Pha Tad Ke garden, before it’s gone forever.

Savanhdary Vongpoothorn:

A Bridge Between Worlds

Niagara Galleries

(Melbourne/Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Country VIC)

1—25 October

This article was originally published in the September/October 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.