Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

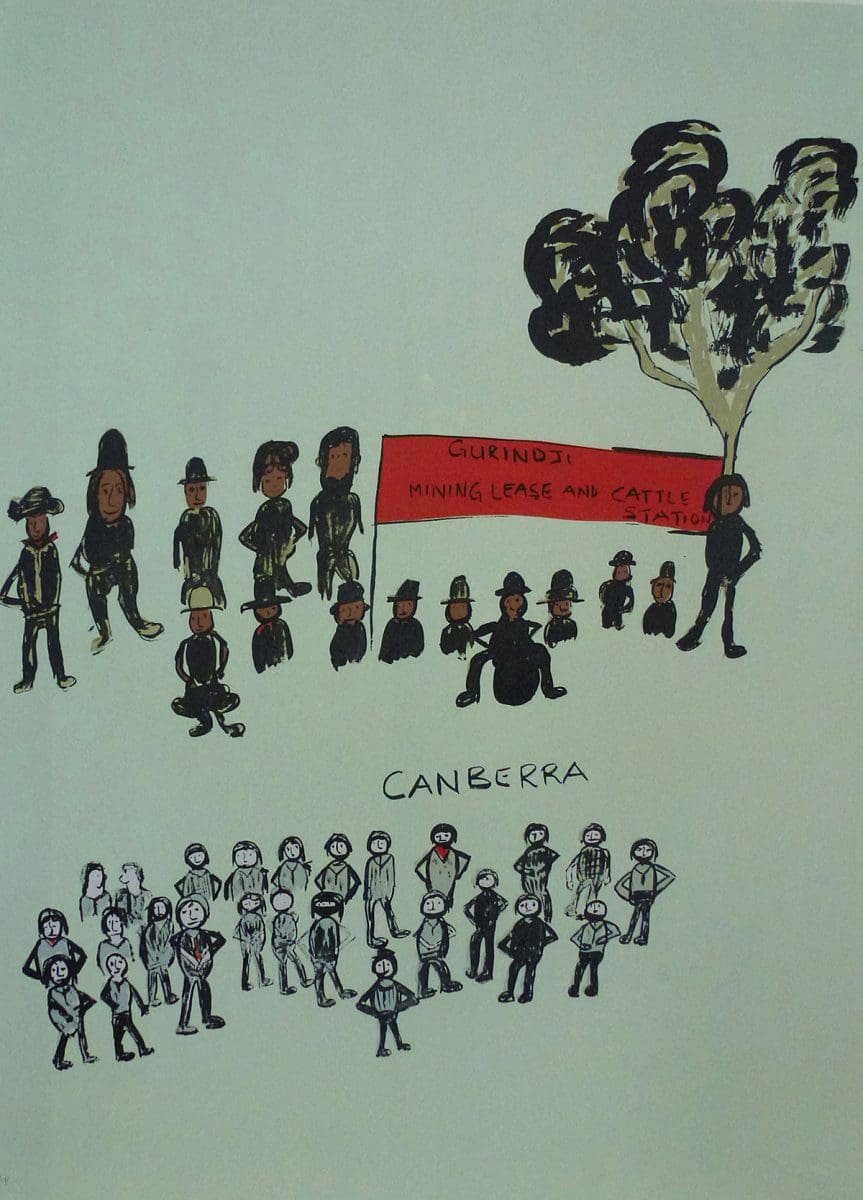

In 1966 Gurindji leader Vincent Lingiari led some 200 Indigenous people off the Wave Hill cattle station in the Northern Territory. They literally walked across the desert, away from a life of inequality and hard labour. In the mid-1960s their wages were less than one sixth of what white people earned for the same work. Earlier generations of Aboriginal workers on cattle stations had not been paid at all; they were slaves in all but name.

In 1967, Lingiari and three other Gurindji leaders wrote to the Governor General of Australia. “Our people have lived here for time immemorial and our culture, myths, dreaming and scared places have evolved in this land. Many of our forefathers were killed in the early days while trying to retain it,” they said. “Therefore we feel that morally the land is ours and should be returned to us.” The National Land Rights movement had begun.

Fifty years later, the group exhibition Still In My Mind: Gurindji location, experience and visuality examines the Wave Hill walk-off, its legacy, and the ongoing repercussions of dispossession from multiple perspectives. Curator and exhibiting artist Brenda Croft points out that while the show marks an historic event, the victory it symbolises (in 1975 the Whitlam government returned some Gurindji land to its traditional owners) is far too bittersweet to warrant the word celebration.

“Looking back at events like the Wave Hill walk-off, there is always a desire to romanticise them and think that everything was fixed. And it certainly wasn’t,” Croft says. “I prefer the term commemoration.” And she’s right. Language matters.

Despite centuries of dispossession, and government-sanctioned incarceration during the years of the Stolen Generations, the Gurindji language survives and it can be heard in both audio and video recordings in Still In My Mind. And stories told by Gurindji elders in their own language for the 2016 book Yijarni, then transformed into paintings, form a key part of the exhibition.

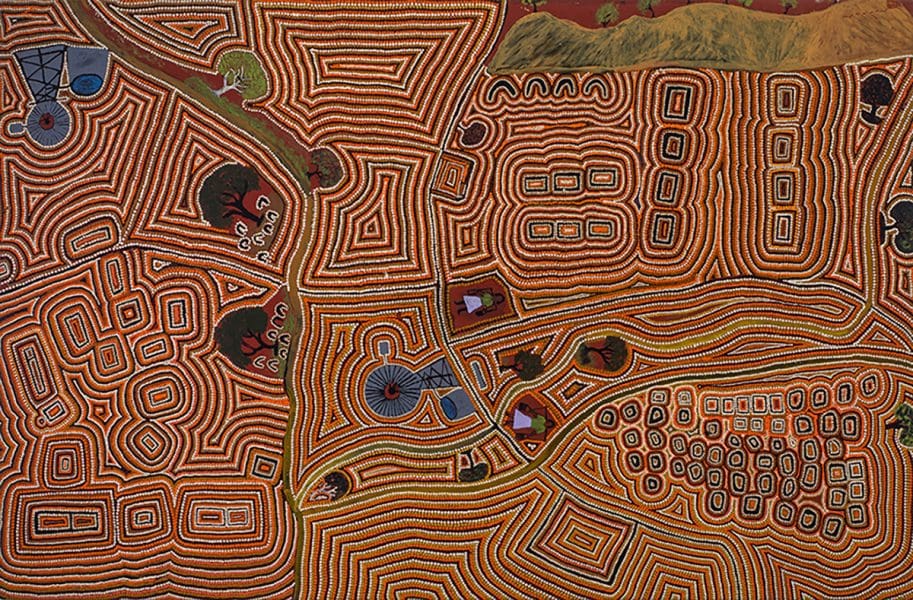

In Aerial view of Jinparrak (Old Wave Hill Station), 2015, Biddy Wavehill Yamawurr Nangala and Jimmy Wavehill Ngawanyja present a kind of map from memory. They paint water bores, special trees and buildings that they recall from their days at Wave Hill station, all joined together by rhythmic patterns of dots in black, white, orange and brown. These painters, like the other Gurindji elders, tell a first-hand account of dispossession.

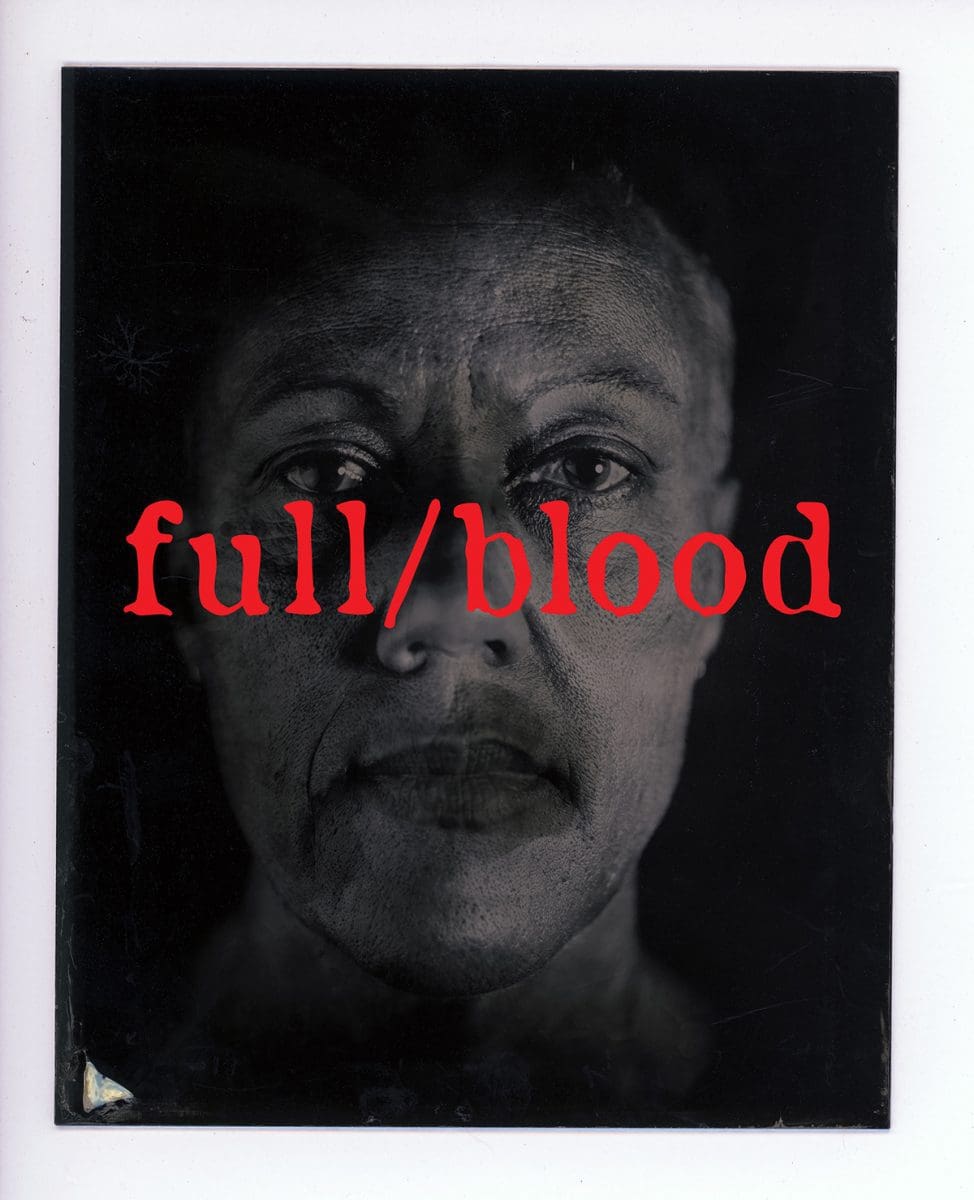

Others, such as Croft herself, have different stories to tell. “I’m a middle-class Indigenous person,” she points out. “I’ve had the benefit of an education, and I’ve got the tools to advocate on my own behalf.” Yet she is still judged by the colour of her skin. “You are too white for some and not black enough for others,” she says.

Croft tackles the tricky topic of race head-on in her 2016 photographic series, blood/type. In these self-portraits she replicates taxonomic ethnographic records and labels herself ABO.riginal, Native, quarter/ caste, HALF-CASTE, and octaroon.

Elsewhere Croft tries to come to terms with the loss of country from the perspective of someone who hasn’t actually lived there. The effects of being displaced reverberate through the generations. Croft’s father Joe was one of the Stolen Generations, removed from Gurindji land when he was just one-year-old. In Still In My Mind, through both still photography and video, Croft documents her own journey along the 22 kilometre Wave Hill walk-off track, and tells her own story of loss and recovery.

And these works, like most of the works in the show, are tinged with hope.

“The exhibition title is from a statement that Vincent Lingiari made,” Croft explains. “He said, ‘That country,

I still got it in my mind.’ He’s thinking about it. It is in us, and if it’s in my mind, it’s in me.”

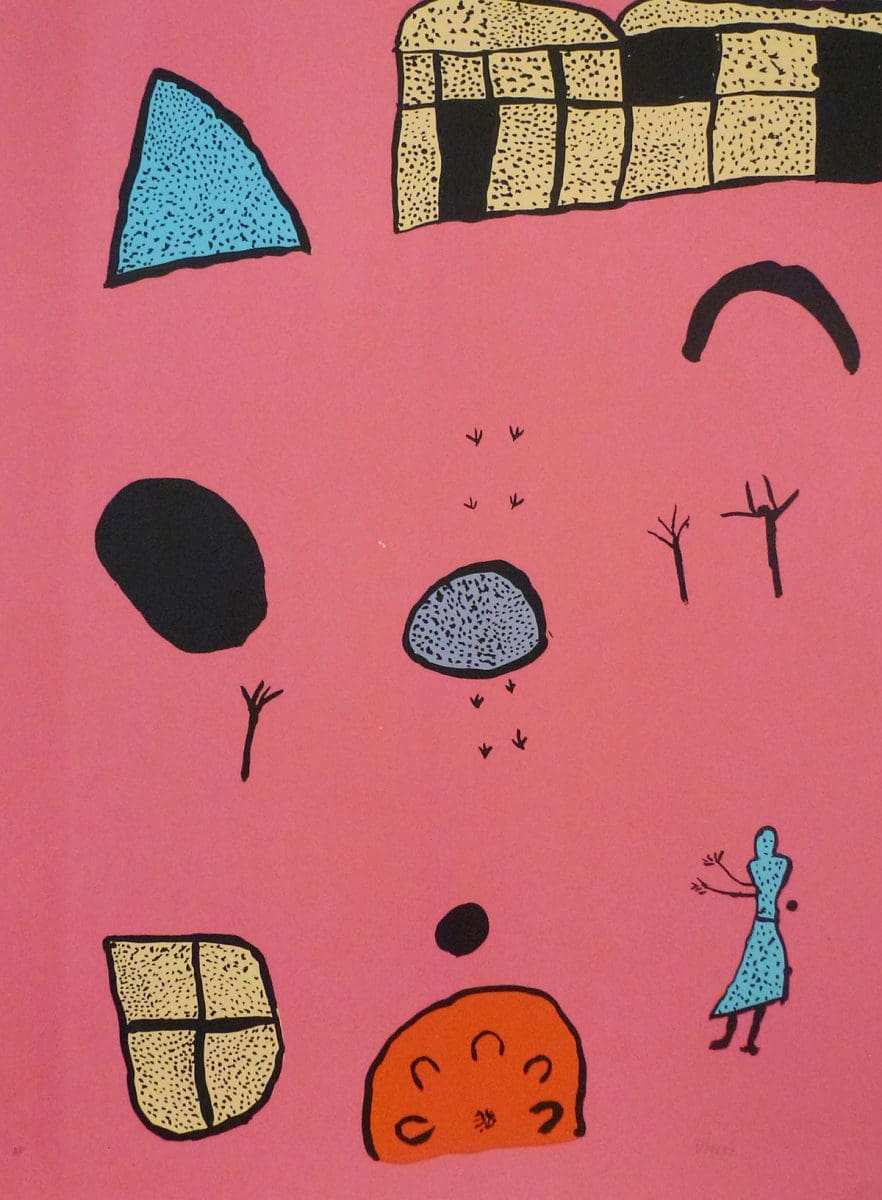

Still In My Mind is a densely layered show encompassing multiple stories from varied points of view. In addition to Croft’s prints, photographs and videos, and new paintings by Gurindji artists, there are also archival photographs and a wide range of artefacts from the old Wave Hill station.

Viewing Still In My Mind takes time. “This isn’t a 20 minute show,” Croft says. “I want people, when they see the exhibition, to hear the voices and to see the stories, to take time to look at all the archival material.” And, she adds, “It’s not a dead archive. It’s a starting point.”

Still In My Mind: Gurindji location, experience and visuality

UNSW Galleries, Sydney

5 May – 29 July

UQ Art Museum, Brisbane

12 August – 29 October