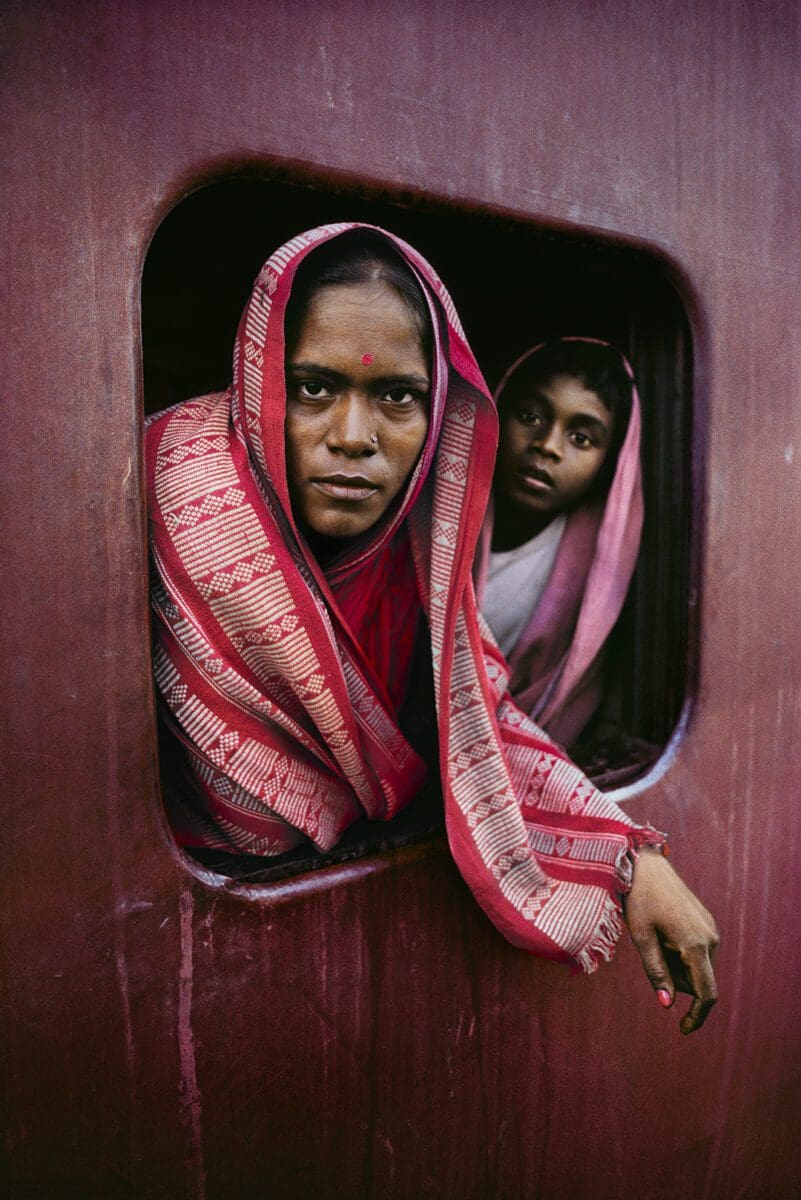

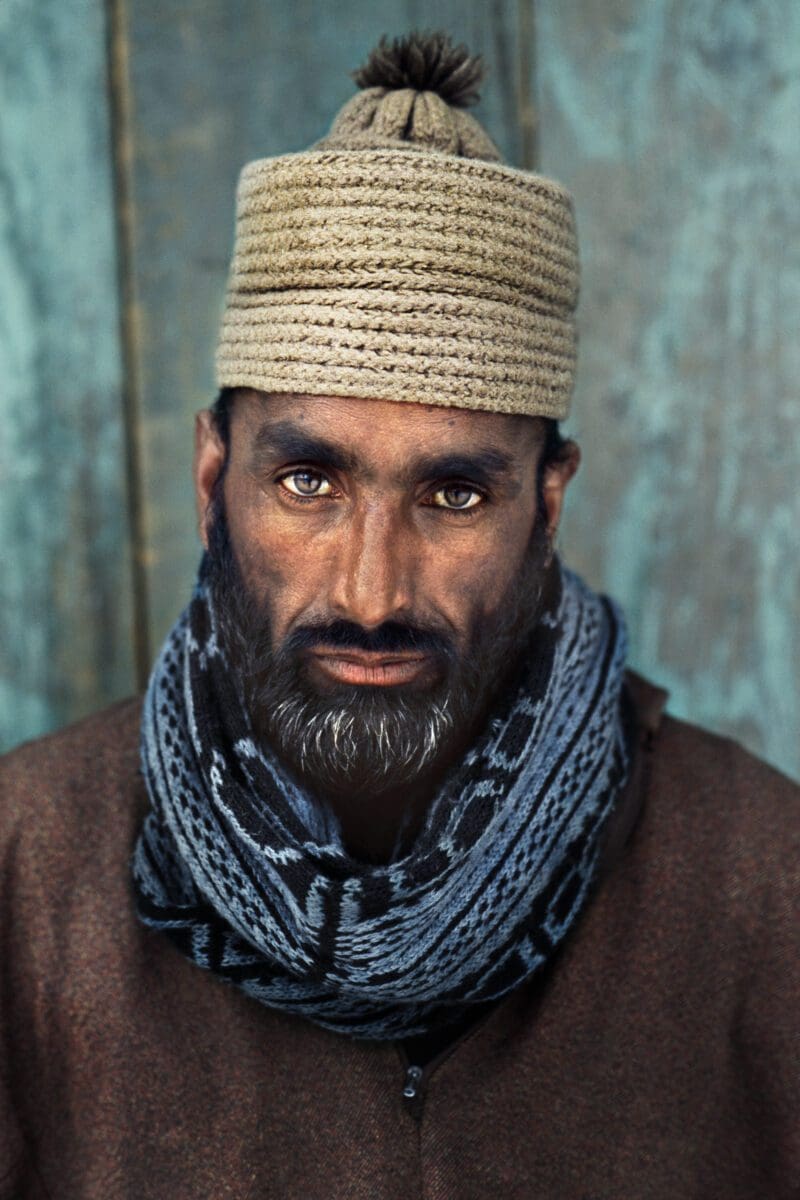

When aspiring photographers ask Steve McCurry for advice, he rarely mentions cameras or technique, but instead tells them to leave home. Trekking his adult lifetime across the Middle East, Asia, Africa, South America and eastern Europe, the US-born portraitist and chronicler of unguarded moments heeds the guidance of American travel writer Paul Theroux: “go as far as you can—become a stranger in a strange land”.

McCurry’s career began more than 40 years ago when he left home to travel and photograph through South Asia, entering Afghanistan with a group of Mujahideen in 1979. McCurry today cites Theroux’s advice to “acquire humility” as a traveller, and will usually hire a locally based assistant to translate languages and advise on customs.

None more so, perhaps, than McCurry’s arresting portrait of a 12-year-old Pashtun girl, Sharbat Gula, taken in a refugee camp and which appeared on the cover of National Geographic in 1985. The image came to define his body of work and the plight of many asylum seekers.

“Sometimes you inadvertently make some social faux pas, and you need someone to say, ‘Hey, you can’t do this culturally, it isn’t cool’,” he says from Philadelphia. It’s the city where he was born and still lives with his partner Andie Belone, a Native American of the Hopi tribe, and their daughter Lucia, aged six—when taking respite from travelling the globe half the year.

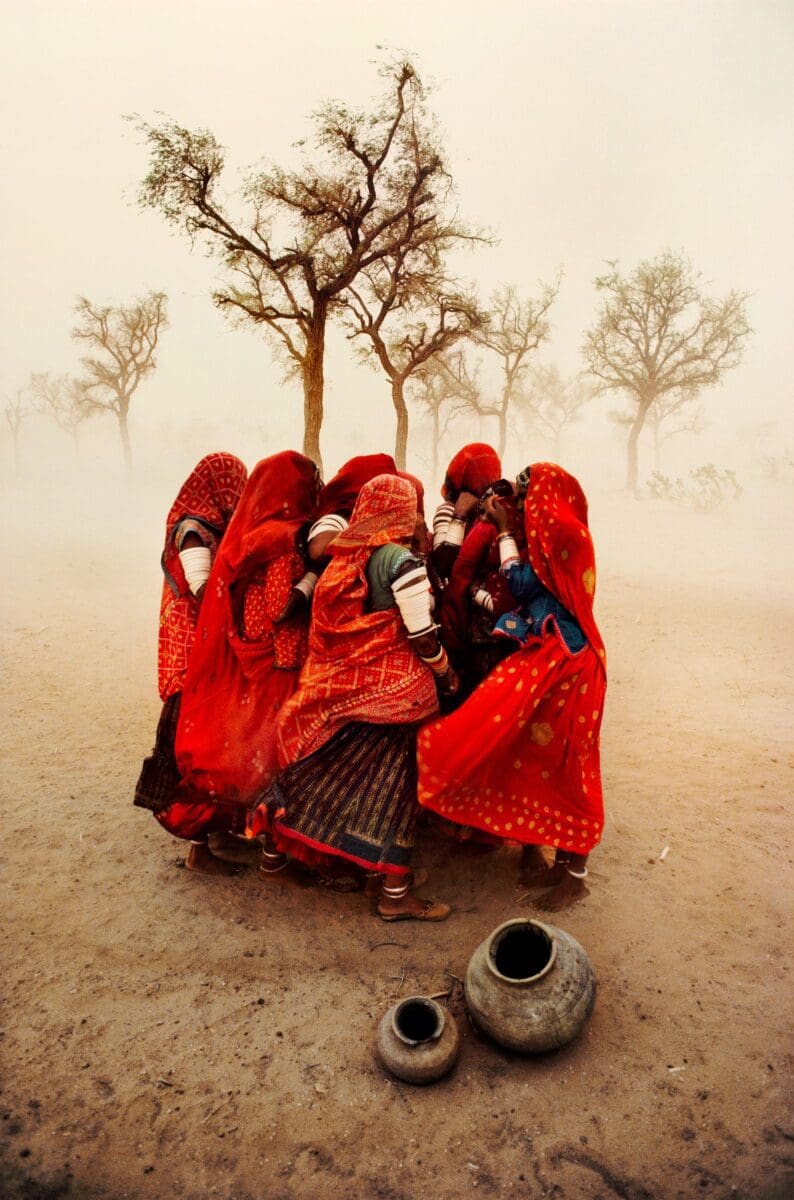

For a new retrospective survey of his work now on display in Sydney, the 72-year-old has chosen more than 100 large-scale photographs that had a profound effect upon him. This exhibition, ICONS, is a “personal diary of people and places that touched me and were important”, he says.

None more so, perhaps, than McCurry’s arresting portrait of a 12-year-old Pashtun girl, Sharbat Gula, taken in a refugee camp and which appeared on the cover of National Geographic in 1985. The image came to define his body of work and the plight of many asylum seekers.

For over a decade after that image was published, Gula “got a tremendous amount of help from all sorts of people”, McCurry recalls. “Then the Pakistanis cracked down and had her arrested and she went back to Afghanistan and was treated like a returning dignitary hero.”

How does he personally decompress after he photographs individuals fleeing war and persecution or children forced into labour?

He photographed Gula again in 2002. “Now she’s living in Italy, thanks primarily to my sister who worked very hard to get her and her family out of Afghanistan. I think [the attention] has been of huge benefit [to her]—a couple of her children went to school; that would not have happened if she was still back in Afghanistan.”

On McCurry’s Instagram feed, his more recent portrait of a young girl is captioned “Let Afghan Girls Learn”, under which he writes of the “hypocrisy of the Taliban sending their children abroad to study while refusing to let millions of girls be educated in Afghanistan”.

He says now: “The Americans, Australians, Europeans were there 20 years, and it didn’t work out. We can slowly try to help people individually, but I don’t see our governments getting too much involved. The Taliban has an evil approach to education, to freedom of the press and freedom of speech, and I don’t know how that’s going to change.”

How does he personally decompress after he photographs individuals fleeing war and persecution or children forced into labour? “You have to somehow just deal with it and try not to dwell on the past. By telling these stories, you live on the hope that what you’re doing is of benefit to whoever that happens to be [photographed].”

With McCurry’s fame has come scrutiny of his work. When an Italian photographer pointed out in a blog that elements in a print of a McCurry street photo in Cuba had been altered, McCurry blamed a lab technician who printed and shipped the image in his absence. In 2016, the photography website PetaPixel presented two more McCurry images it alleged had elements removed, including human figures.

In his written response to PetaPixel, McCurry said his work has evolved from photojournalism to visual storytelling. McCurry tells Art Guide this evolution means he now satisfies his own curiosity rather than the deadlines and demands of an editor—but does being a visual storyteller give him licence to remove elements from a photograph? “I don’t do that,” he says. “That was kind of an aberration. I don’t do that. I welcome you to come to my studio and we can sit down, side by side, and we can go through the pictures together.”

“Let’s see how it plays out,” he says. “I think we’ll prevail, I think we’ll come out the other side, but we had a civil war, remember, and we survived that.

During the pandemic, McCurry was forced to stop travelling, but he found relaxation in time with his family and looking back at his work. Now that the world has opened up, he is travelling again, having just returned from Dubai and Thailand after treks last year to the Galapagos, Guatemala, Ecuador and Peru, and is soon off to South Africa and Botswana.

Sometimes, his partner Andie and their daughter Lucia travel with him. “With your kids you just want them to find their own path, something that’s enriching, whatever that may be. To get a good education, have an open mind, be curious.”

McCurry is suspicious of certitude, particularly of the future. In 2018, he criticised then US president Donald Trump for being “racist” in questioning his presidential predecessor Barack Obama’s citizenship and place of birth. How is the photographer feeling about his own country now that Trump has been indicted on criminal charges?

“Let’s see how it plays out,” he says. “I think we’ll prevail, I think we’ll come out the other side, but we had a civil war, remember, and we survived that.

“We live in a world now that is ‘what is truth?’. We’re in a post-truth world. Everybody has their own sense of truth. You have people on one side saying one thing and the people on the other side saying something else, and they’re both completely locked into their point of view.

“So,” he turns his mouth down, raises his eyebrow and shakes his head, “I don’t know.”

ICONS

Steve McCurry

From February 2024

Seaworks Williamstown