There is a sense of unfolding narrative in Julie Fragar’s survey exhibition, Biograph. Curated by Jonathan McBurnie, the narrative of Biograph is not linear, it weaves in and out, like pinned snapshots chronicling several years of a person’s life on a kitchen corkboard.

Through Fragar’s 23 years of painting and photography, common themes emerge—family history, portraiture and moments of despair and elation both personal and public—to represent the complexities of lived human experience. With Biograph spanning work from 1998 to 2021, we talk to Fragar about the trajectory of her art making, creative influences and what it’s like to observe a Supreme Court murder trial.

Briony Downes: Much of your work contains self-portraiture. Why is it important to include elements of yourself in your artwork?

Julie Fragar: All my work is about people and close-up human experiences, so part of that has meant, at times, painting in the first person. Artists referring to themselves in their work is super interesting to me. When artists like Jenny Watson put themselves in their work, they conjure a kind of author character we interact with, and I think those interactions can tell us a lot about how we connect with one another in real life. Especially around what we expect from and project onto each other.

“The pure text works are another thing. You can start with a good story or phrase and make it behave in all kinds of ways depending on how you paint it.”

BD: How would you say your text paintings co-exist with the image-based work as a form of storytelling?

JF: I like playing around with content and form, using text both with and as an image has a lot of appeal. The paintings with text on top or embedded in the images are what I started with, and they operated like the titles had busted onto the painting.

The pure text works are another thing. You can start with a good story or phrase and make it behave in all kinds of ways depending on how you paint it. I have made some excruciating-to-view long-form narrative paintings with no gaps in the text that almost nobody would be bothered to read the whole way through. But those also have this nice effect of strained communication with, hopefully, a pay off at the end. Others are easier to consume and refer to the site of the painting, ones like MEETMEATANARMSLENGTH, 2010, or THISISWHERETHEFOGLIFTS, 2008, feel gentler and more intimate, making a kind of you, me and the painting viewing experience.

BD: Looking back on your career, what has art revealed to you about yourself?

JF: That I don’t like work that makes me stand in one place for an extended period without the possibility of escape. Or that makes me go in a dark space where I think I’m going to trip over the whole time. The art of others tells me I prefer quietish things, with some exceptions, and work that shows a real sensitivity to materials.

I also like work that makes a genuine effort to be generous and that can come in a whole range of ways. I like equally installations by Thomas Hirschhorn, Franz Erhard Walther’s wearable sculptures, Kyra Mancktelow’s prints and the paintings of Frans Hals, Agnes Martin and Diena Georgetti because they are all masters of their materials and have a great deal of human sensitivity. As far as my own work goes, I can see I’m a ruminator. I like looking at things from an analytic perspective and enjoy trying to solve problems, especially material and psychological ones.

BD: How do you go about this?

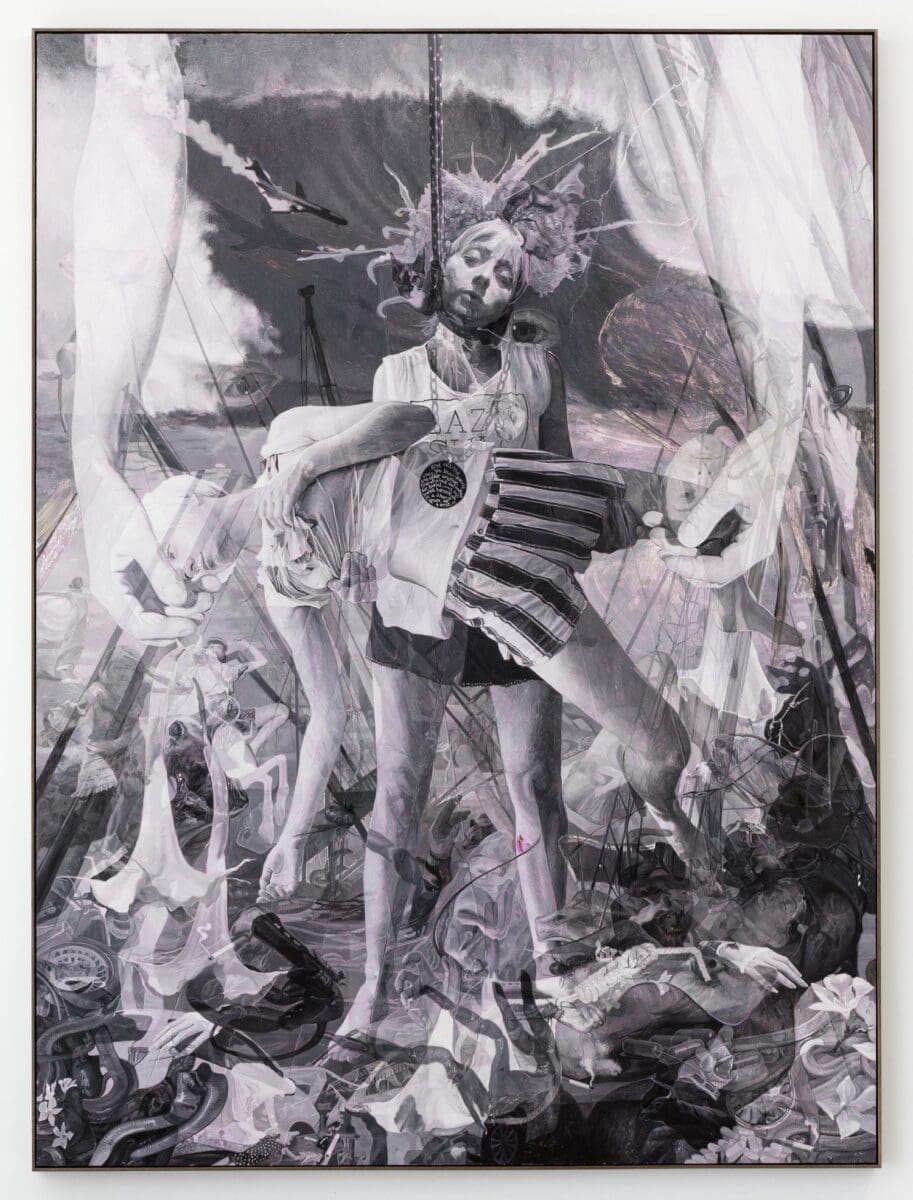

JF: The series of works I made after witnessing two murder trials at the Supreme Court of Queensland are good examples [a selection from both are in Biograph].

The first series, Trial Paintings, 2017, were small speculative paintings on paper that brought together the facts and arguments of the case and had a strong sense of someone trying to piece a story together or figure something out.

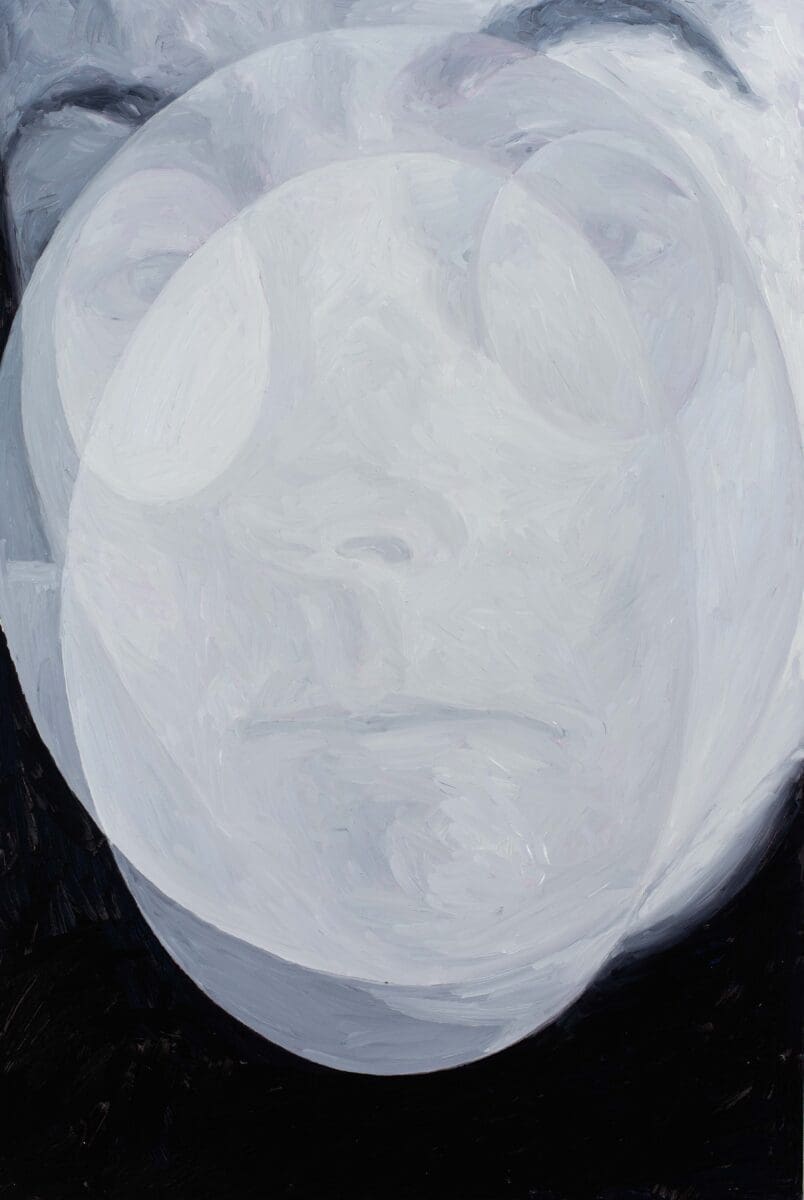

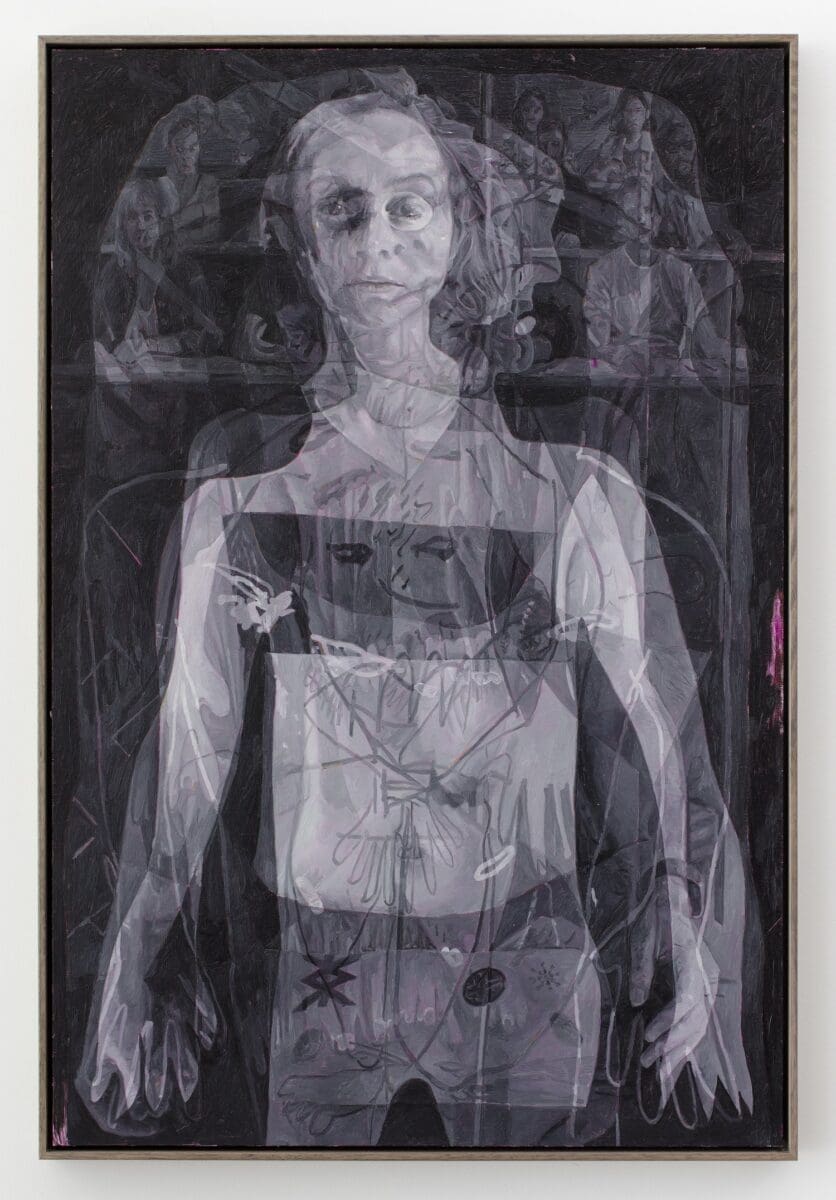

Documenting the second trial in the series Next Witness, 2018, I avoided the salacious, and absolutely tragic, narrative of the trial and instead looked for ways to visualise lived experiences of the court. To do that, I broke the institutional process of the trial into distinct human parts; the judge, the jury, the barristers etc. There was one painting called The Gatekeeper (Portrait of an Honourable Justice), 2018, which was about the way a trial judge must hold and process every detail of the trial; it’s not a job many people could do and I’ve no idea how they handle the strain. That painting is a portrait of Honourable Justice Deborah Mullins AO surrounded by visual references of trial details and participants, roughly arranged in concentric circles to create the effect of building visual pressure onto her head.

“The paintings that include my kids, Penny and Hugo, are the most meaningful.”

BD: Some of the works in Biograph have rarely been exhibited. Can you tell us about them?

JF: Apex Jumping Castle was a series I made in my Honours year at Sydney College of the Arts in 1999. It was part of a grad show and hasn’t been shown since. Some of the paintings in this series have been substituted, given or packed away, so in Biograph it’s a slightly edited version. It was important to include because it marked a starting point for my long-term interest in the personal, the photographic and painting; starting with most basic exercise of painting miscellaneous personal snapshot photos 1:1. There was nothing earth-shattering about that from an artistic perspective, but it cemented a kind of obsession with how things appear when they are turned into paintings.

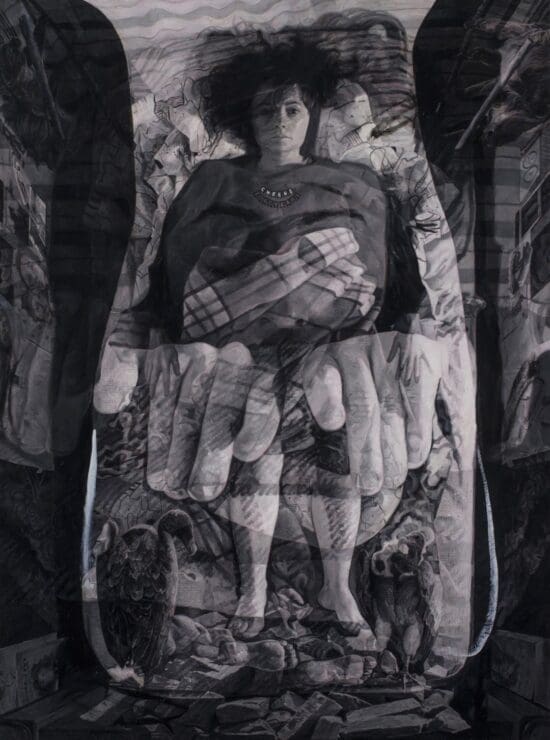

Another work, Grandma (Alzheimers), 2008, was shown once at Lismore Regional Gallery many years ago. It’s a painting of my maternal grandmother when she was quite ill (though nowhere near as ill as she became). Lots of people have had the experience of having a loved one slowly emptied out by Alzheimers or dementia and grieving in increments.

BD: Is there a particular work in Biograph that really means a lot to you?

JF: The paintings that include my kids, Penny and Hugo, are the most meaningful. The image of Hugo posing as my Azorean ancestor Antonio de Fraga in Off Sure Feet, 2014, is a very special one; at the end of boyhood, falling toward the rest of his life. And in a similar way Ready (Penelope), 2008, a painting of a wise and determined little Penny with her ‘grown up lady with earrings’ drawing over the top, who, as it turns out, was indeed ready for all the joys and challenges that have come since.