At the 1938 Day of Mourning, activist pastor Sir Douglas Nicholls KCVO OBE made an impassioned plea for an end to colonial oppression. “We do not want chicken-feed,” he said. “We are not chickens—we are eagles.”

The ninth TarraWarra Biennial takes its name from this poetic statement. We Are Eagles, curated by Yorta Yorta woman Kimberley Moulton, has three core thematic pillars: regeneration, restoring spirit and disrupting colonial space. Over 20 artists present new commissions responding to these ideas. “Contemporary art can really restore and give voice to not only objects, but also memory and place,” Moulton says.

Moulton applies a First Peoples curatorial approach to the Biennial, which shapes the form of the exhibition. “My practice is very much centred on relationality: building relationships, understanding artists, connecting to place, connecting to their research,” she says. “We’re expanding on what Indigenous curatorial practice can be.”

Warraba Weatherall:

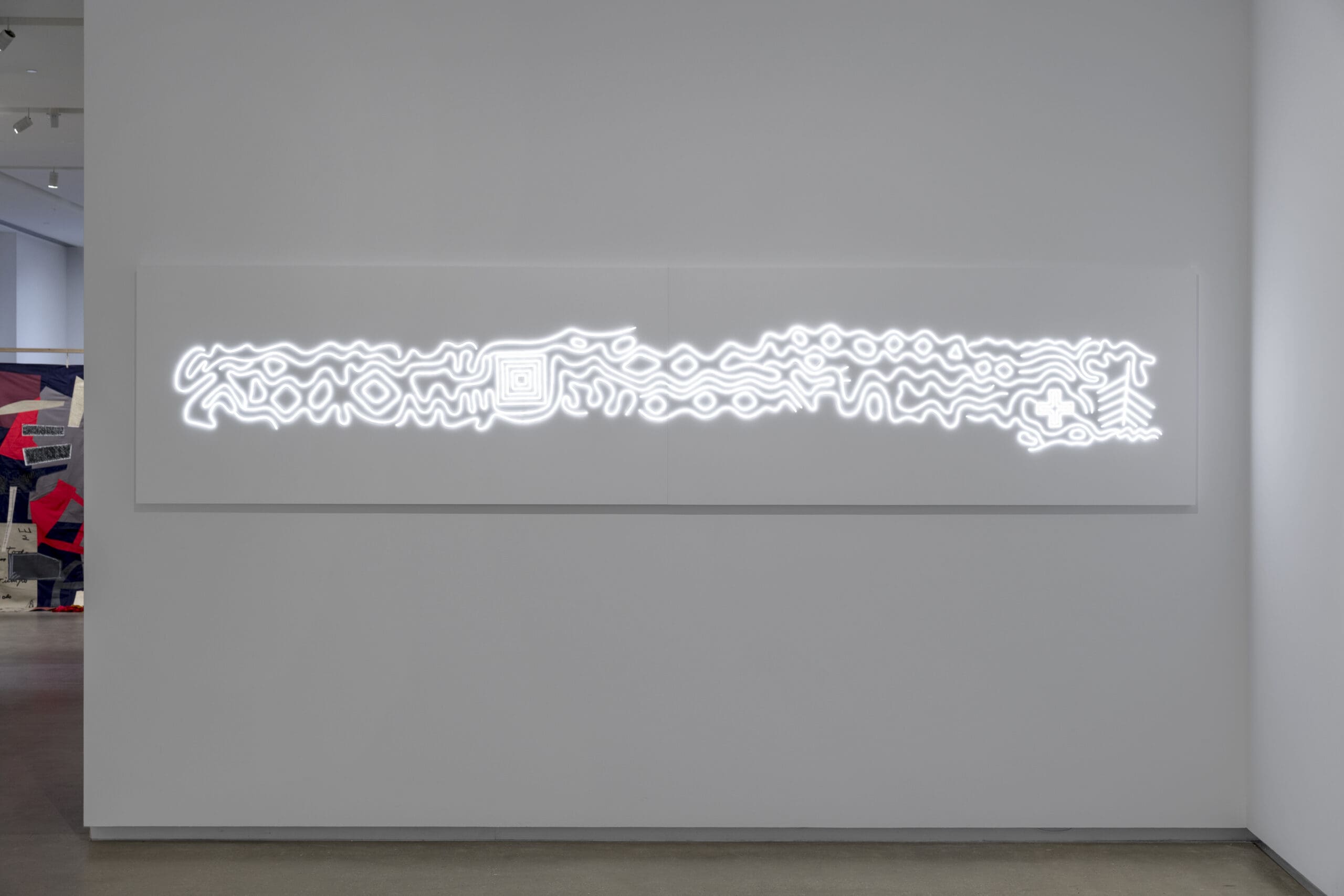

Across years of doctoral research, Kamilaroi artist Warraba Weatherall has studied countless archival records, many made by non-Indigenous anthropologists. One such document had separate designs that Weatherall began to regenerate. In this process, he realised that they belonged together as a whole image. “It’s a cultural design that’s very significant,” the artist says.

Now, Weatherall is bringing the reunited designs to life as a large-scale light installation—the first time the artist has worked in this medium. “Thinking about the relationship between the design, its intention, its meaning and some of those reference points to cultural knowledge and constellations, I thought it would be fitting to look at light as a material,” he says.

In creating the light work, Weatherall considered the ethical implications of showing these sacred designs to a wider audience within the context of colonisation. “Many of our cultural practices and ceremonies are not continued and conducted anymore … The unfortunate thing is that our contemporary experience is so far removed from that history,” he says. “It’s a delicate process, not wanting to contribute to the further bastardisation of cultural knowledge.”

But on the other hand, cultural knowledge has been shared for time immemorial—so these designs will mean something deeper and different to the Indigenous people who see them. “Historically, cultural knowledges, particularly around sky knowledges, were something that was widely understood and taught to younger children within communities,” Weatherall continues. “There are things that are related to the designs and the processes that have sensitivities, but the design itself and what it actually depicts doesn’t.”

With this light work, Weatherall hopes to keep these cultural designs alive, and communicate their codified meanings to those who have ancestral ties. Others must understand the limits of their knowledge, he says. Whatever their background, he hopes the value of the project will be clear to everyone who sees it, and “that people can appreciate and get a glimpse into a cultural reference point that has been expressed in a contemporary way through the light installation, and understand that this is an ongoing process of regeneration.”

wani toaishara:

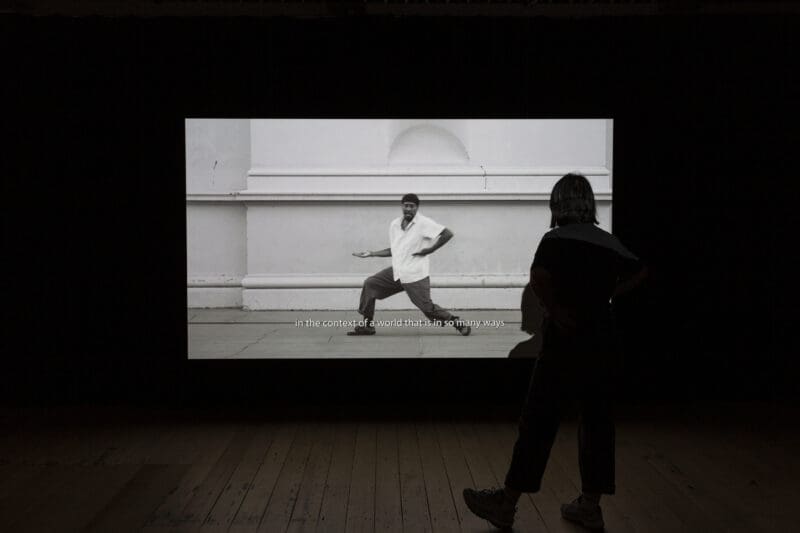

wani toaishara is creating a new artistic language. Rather than memory, the Congolese artist speaks about “re-memory”, and rather than representation, “re-presentation”. It is a statement: we have always been here.

“Because our culture has never stopped, I don’t believe we’re representing anything, but I believe we’re always presenting what has always been,” he says. “With the idea of memory, I think of it in the same way—it’s a re-memory of what my body’s always known.”

toaishara’s work has long explored Blackness, statelessness, climate change and dislocation. At TarraWarra, he presents a new two-channel video piece that builds on these ideas, as well as tying into the Biennial’s themes of regeneration, restoring spirit and disrupting colonialism. “For this work, I draw inspiration specifically from … my personal story, the hypervisibility of the Black body on the political landscape, and particularly the idea of both soil and different bodies of water,” he says. “I’m thinking through different techniques that help us perceive space and presence.”

The abstract video plays on imagery of water, soil and bodies to present a metaphorical imagining. “I have combined visual mediums with performative elements, trying to create immersive experiences, whether it’s how the body moves, or other bodies, thought through in the different ways we’re in the same body,” toaishara says. “I’m specifically really interested in the Black body and how it relates to ourselves.”

Before turning to visual art, toaishara was a spoken-word poet. For this commission, he combines these two worlds, with a written piece displayed alongside the video work. He’s also experimenting with different forms of photography: “I’m integrating a form of performance within the work—I’m really interested in studio portraiture photography and how it was used before [compared] to how we use it now.”

In this work, toaishara does not focus on relationships to colonisation or whiteness—rather, he turns his gaze towards his own community. “That’s where the theme around water and soil comes from,” he says. “When you plant something in soil, it grows.”

Shireen Taweel:

In 2024, Shireen Taweel undertook a pilgrimage across Aotearoa and Australia—her own version of Hajj, the annual Islamic journey to Mecca. “It was quite significant as a way of bringing forward futurism, of thinking of … pilgrimage and celestial navigation, particularly aligned with sacred practice,” says the Sydney-based artist.

Taweel’s research in Arabic astronomy informs her project Pilgrimage of a Hajjanaut. Through her investigation, the artist learned that Western sciences are largely founded within the Arabic scientific framework. “A lot of what we know in the West has been reappropriated from the East,” she says. “The Arabic science that I’ve been researching is actually very much embedded in the infrastructure of space activity and in all forms of mathematics that we rely on today … Stars have Arabic names too within the Western language of mapping astronomy.”

The artist used her skills in coppersmithing to make her own celestial instruments, including a qibla (compass), quadrant, sundial and astrolabe. “There’s been a really wonderful material development around the projects of pilgrimage,” Taweel says. “It’s been a generative [approach to] methodologies [which] consider decolonial practices across the earth, but also across space.”

For this project, Taweel had initially called herself a Hajjonaut, but swapped the O for an A as an “indicative nod towards the feminine”. The costume she wore for the journey—and in the video documenting the pilgrimage—engages with pilgrims’ cloth and materiality, as well as the textiles of space exploration. “There are so many different rituals that come into the journey,” she says.

Taweel’s experience of embarking on the physical journey after this exhaustive research brought what she’d learned to life in a magical way. “Up until my pilgrimage project, I’d been so deep in research and handling the instruments, looking at them, examining them, talking about them,” she says. “It wasn’t until I was culturally applying the well of knowledge I had accumulated … that it really started to move so beautifully, in a way that [brought] such a different sense of meaning to understanding our connection to the greater cosmos.”

TarraWarra Biennial 2025: We Are Eagles

TarraWarra Museum of Art

(Healesville/Wurundjeri Country VIC)

On now—20 July

This article was originally published in the May/June 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.