Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

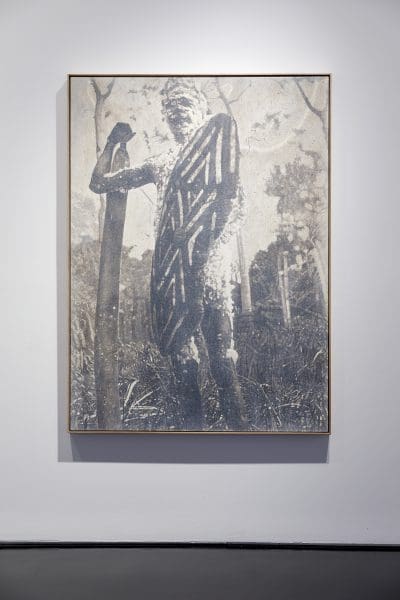

Danie Mellor’s new online exhibition at Tolarno Galleries, The Sun Also Sets, made up of paintings and large-format photomontages, is a deeply considered meditation on time, culture and the notion of ‘landspace.’ It is also an insightful and inventive musing on the relationship – and distinctions – between photography and painting. Barnaby Smith spoke to the artist about his inspirations and intentions for a show that is on one hand a time capsule, and on the other poses many questions of contemporary relevance.

Barnaby Smith: Firstly, can you give some context to the sense of cultural duality in the exhibition? The Sun Also Sets engages strongly with indigeneity and colonialism, yet the name of the show stems from Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises (Hemingway himself took the title from Ecclesiastes), and the tile of one piece comes from Dylan Thomas. These are obviously references to a Western European tradition. You’ve spoken before of ‘shared history,’ is it something to do with that?

Danie Mellor: To some extent. In my early career I spoke of shared histories, but it’s important to note it was an involuntary and often violent form of sharing as a result of historical colonialism.

As to the origins of the title of the exhibition, I am interested in how cultures arrive at philosophical understandings around the cyclical nature of life. Whether those stories and intellectual signposts or markers, in this case the titles you mention, have an Aboriginal or non-indigenous source is not always significant, as each can lead to similar spaces of reflection.

BS: How does this exhibition expand on ideas explored in your previous exhibitions?

DM: I’m hoping it expands on my thinking around the proposal of a ‘landspace,’ rather than simply the landscape. The landspace is something I first wrote about in relation to my last exhibition at Tolarno Galleries, The Landspace: [all the debils are here], 2018, as being conceptually and culturally inclusive, allowing for encompassing worldviews of Country to co-exist with all other ways of considering landscape.

It’s a subtle shift, but it opens a raft of new possibilities in terms of how we envision real and intangible responses to our environment. I have found that thinking in terms of a landspace activates a quantum understanding of cultural narratives in relation to time, particularly when considering the simultaneity of past, present and future that is the foundation of ‘everywhen’ in Aboriginal cultures.

BS: Can you describe the journey of how you turned to painting, as opposed to other mediums, for this show?

DM: It’s a turn and return, as I painted during my early career, although I only rarely, if at all, exhibited paintings. It seemed the right moment for this exhibition, given my continuing interest in painting and its relationship with photography.

I remember as a student being taken by early modern history and the relegation of painting to its death as photography gradually became an accepted art form. I’m interested in artists like Chuck Close, Gerhard Richter and to a lesser extent Sigmar Polke, as their photographic sources – particularly for Richter – become documents the painting ultimately reflects, so there is a kind of internal truth revealed in completed images as a result of that relationship.

I felt that in coming to a decision about what to produce for The Sun Also Sets, it was timely to consider bringing the two mediums together in some form of dialogue.

BS: So it feels like The Sun Also Sets is making a point about photography as it relates to history, and its distinction in this way from painting. Is that fair?

DM: Yes. There is something about the way photography, and by extension the subjects of its imagery, was objectified and even commodified, which is very modern. What interests me is the way images are constructed. I write in my introductory text to the exhibition about Susan Sontag’s suggestion that a painter constructs while a photographer discloses, which I find a very attractive idea.

However, I have found by being engaged with both photography and painting in one body of work, that construction and disclosure are mutually inclusive and a vital element of research and imagination. A key point for me has always been about the reading of the image, and how its construction or inherent complexity is either understood or not.

BS: The exhibition’s accompanying essay (by Tony Magnusson) refers to your great-great grandmother Ellen and the photos taken of her by the photographer Alfred Atkinson. How have these images been particularly inspiring for your work?

DM: The archive of portraits we have of our Aboriginal family left a deep impression on me from an early age. It wasn’t simply that the images were haunting and beautiful, it was also the materiality of objects from the early 20th century.

The connection was made living through my great-grandmother, who I knew into my teenage years and who also appeared in studio portraits taken by Atkinson. I have spoken before about those portraits being images that reflect the world and the changes occurring when they were taken, rather than simply formal or intimate pictorial records of family.

At the time, photographers like Atkinson were active in late colonial northern Queensland, when Aboriginal people were experiencing devastating social and cultural interruptions, and this affected my family also.

BS: Can you expand on your affinity for photography from the early 20th century and before? What specifically are you looking for in photos from that time?

DM: I look for a sense of reverie and introspection, but search for feelings of separation as well. When I can identify specific areas or landscapes in photographs taken by Atkinson and even Walter Roth, the Northern Protector of Aboriginals at the time, I try to take my own images of that rainforest country. It’s a performative act on my part that isn’t always successful, but I like the idea of pursuing a conceptually or culturally inverted pictorial record of their field trips; I reference historical photographs in paintings in combination with my own source imagery.

BS: How do you create that inversion?

DM: To introduce an interference and patina to the image, I brush and pour a translucent wash of iridescent medium combined with gesso over the completed painting. It has the visual effect of pushing the image away, making it somehow just out of reach and, in part, unobtainable. It was important to suggest that feeling for the work, as I was unable to travel to the rainforest to gather material in preparation for the show due to the pandemic outbreak and subsequent travel restrictions.

BS: Finally, Magnusson’s essay ends with your question, “Are we making ourselves alone in the world?” This feels particularly relevant now, doesn’t it?

DM: The question has become even more topical in ways I hadn’t intended. I initially posed that question as a way of reflecting on our relationship with the natural world and its ecologies.

While it isn’t particularly novel to point out the impact of humanity on the environment, it may be timely to ask what ultimately will be left? We can’t exist alone; we need the world with all its complexity and the vital, sustaining relationships we have with it.

The Sun Also Sets can be viewed through Tolarno Galleries’ online viewing room. A conversation between Danie Mellor and Tyson Yunkaporta can also be watched via the viewing room.

The Sun Also Sets

Danie Mellor

Tolarno Galleries

7 August – 5 September