Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello’s Glass Acts

Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards 2025 finalist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form.

When speaking with artist Fayen d’Evie, each conversational direction is a pebble dropped in water that ripples outwards, embracing vast universes of ideas and people, material and place, etymology and history—and, within the generative spaces between these things, the dust that constantly circulates.

D’Evie was first drawn to the idea of dust when a conversation with an astrophysicist revealed that interstellar dust clouds hold, as she explains, “the building blocks of life”. That such essential material could be contained in an amorphous ‘between-space’ was a revelation, reflecting a certain way of living. “It was fundamentally, to me, evocative of those of us who live outside the bounds of what is considered the normative colonial patriarchal structures,” d’Evie says. Since then, the artist has embraced the notion of dust as a metaphor for ways of being that are “continually reassembling and circulating”.

As an artist with low and fluctuating vision, d’Evie has been working with ideas around blindness since 2016, when her vision went through a period of rapid degeneration. However, initial experiments with making tactile paintings, created to be touched, didn’t turn out as planned. “I thought that they would end up really beautifully dirty by the end of the show; that’s what I hoped,” she says. “I thought that they would all get kind of worn down by grease and fingertips and old lunch and whatever. And they were pristine at the end! It really broke my heart because I was like, ‘Well, that means people looked at them, but they didn’t actually touch them.’”

Since then, d’Evie has developed a different approach. Examining the English words surrounding blindness, the artist noticed how many of them were inherently negative. “There’s this ingrained sense of blindness as ignorance and, you know, ‘blind drunk’ or foolishness,” she explains. “This is still carried rhetorically, and still endorsed by society within a lot of language—saying somebody is ‘blind’ to something. And while a lot of other pejorative terms are being recognised and extracted, for some reason this one remains, and has been naturalised as okay.”

Seeking to “reclaim the agency of blindness,” d’Evie became fascinated with the idea of ‘blundering’— meaning ‘to stumble blindly’—as a deliberate strategy for “heading out into uncertain terrain”. She describes this blundering approach to writing and art-making not as a position of ignorance, but a means of way-finding. “It’s an openness to uncertainty, and a continual recalibration,” she says. This strategy may draw on blindness, but it’s relevant to a broader audience as well as those who are blind or experience low vision. As d’Evie points out, “Anybody who is visual has a blind spot, and everybody who has a blind spot is actually in a situation where your brain is creating an image for you.”

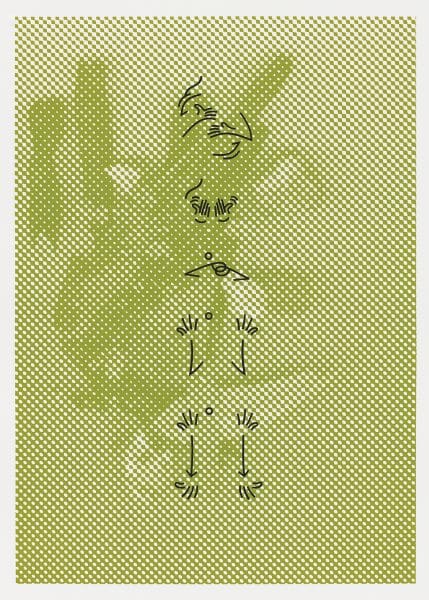

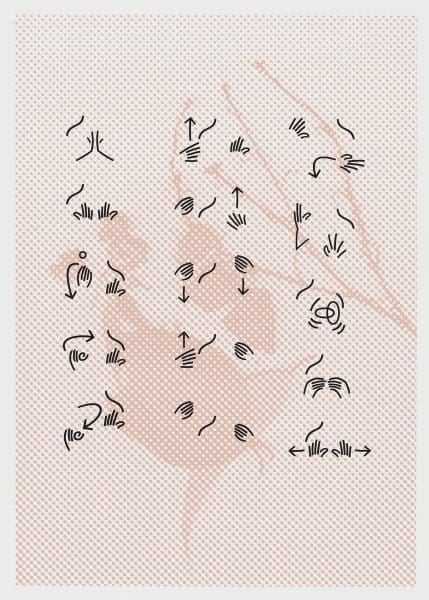

Vision is inherently both unstable and hallucinatory, qualities the artist is fascinated by. She has explored this through multi-layered screen prints, in which printed words are legible from far away but seem to break down the closer you get to their surface. Elsewhere, language—always at the centre of d’Evie’s practice—is made tactile, or sculptural, or conveyed through dance.

D’Evie’s work is remarkable for the poetic sensibility that flows through it, but the artist can’t be pinned down to any one material or technique. A forthcoming exhibition at West Space in Melbourne, although in one sense a solo show, lists almost 30 collaborators, “with more to be invited and confirmed between now and then and during”. These are sculptors, writers, dancers, musicians, poets, performers, publishers, typographers, choreographers, screen printers, and curators. Many are also blind, Deaf, or live with other diverse disabilities; d’Evie’s expansive practice ripples out to embrace numerous modes of being, making, and experiencing.

The exhibition incorporates many notable ‘interventions’. Gallery staff are engaged as active performers—translating, for example, a spoken text in Russian (with Cyrillic subtitles) into both spoken English and Australian Sign Language (Auslan). Other works evoke touch or invite direct handling; a series of bells by blind sculptor Aaron McPeake articulate the space aurally. Instead of a busy opening event— which can be inaccessible for many due to noise and crowding—intimate group encounters will occur throughout the exhibition’s duration.

In another major project—a new commission for the Museum of Contemporary Art, titled With Cane in Hand, I Dance a Duet for One, for Two, for Three, for Four…—the movements of d’Evie’s cane as she dances are translated into sculptures. The original concept for this work involved two dancers—Holly Craig, who is blind, and Riana Head-Toussaint, who uses a wheelchair—developing a dance in response to the music of blind musician Tommy Carroll, a track celebrating unsteady movement. It is, says d’Evie, “a very upbeat, kind of dancey track”.

From here, the dancer’s movements would be motion-captured, and digitally rendered into sculpture. However, Covid-19 travel restrictions nixed this plan. Instead, Craig and Head-Toussaint taught their separate choreographies to d’Evie over the phone. “I realised that what I could do was to internalise the duet in my body,” d’Evie explains. “Every morning at sunrise, I would go across into the bush, because I was a bit shy about people watching me, and I would dance and rehearse and blend the two, listening to Tommy’s music in my ears.”

Translating movement into sculpture via spoken language, d’Evie dances amid the circulating dust. The building blocks of life flicker and whirl; vibrating and reassembling into new forms.

We get in touch with things at the point they break down // Even in the absence of spectators and audiences, dust circulates…

Fayen d’Evie, with collaborators

10 July—22 August

West Space

With Cane in Hand, I Dance a Duet for One, for Two, for Three, for Four…

Fayen d’Evie, with Holly Craig, Riana Head-Toussaint, Tommy Carroll, Bryan Phillips, Kenny Smith and Edwina Stevens

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

September 2021—September 2022

This article was originally published in the July/August 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.