Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

In 2019 galleries and museums across the world are celebrating 100 years of the Bauhaus, the modernist German art, design and architecture school that radically influenced approaches to art creation and education. In acknowledging this centenary, Bauhaus Now! at Buxton Contemporary looks at the contemporary legacy of the Bauhaus and its Australian trajectory; aiming to reflect its radical, collectivist and mystical ideals.

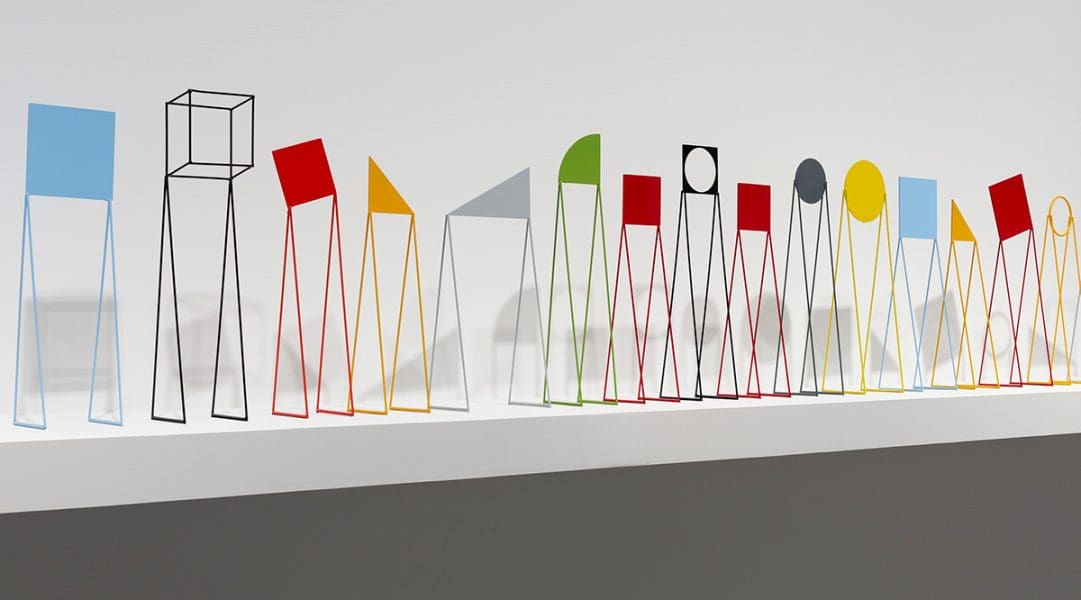

In keeping with the Bauhaus practice of entwining disciplines, Bauhaus Now! spans sculpture, performance, video, installation, works on paper, weaving, instruments, kinetic pieces, toys and sound. Featuring mostly contemporary Australian artists, and a few historical Bauhaus artists, the show side-lines typical Eurocentric historical accounts in favour of introspective views into post-World War II migration, legacy, collectivism, art teaching, occultism and the value of play.

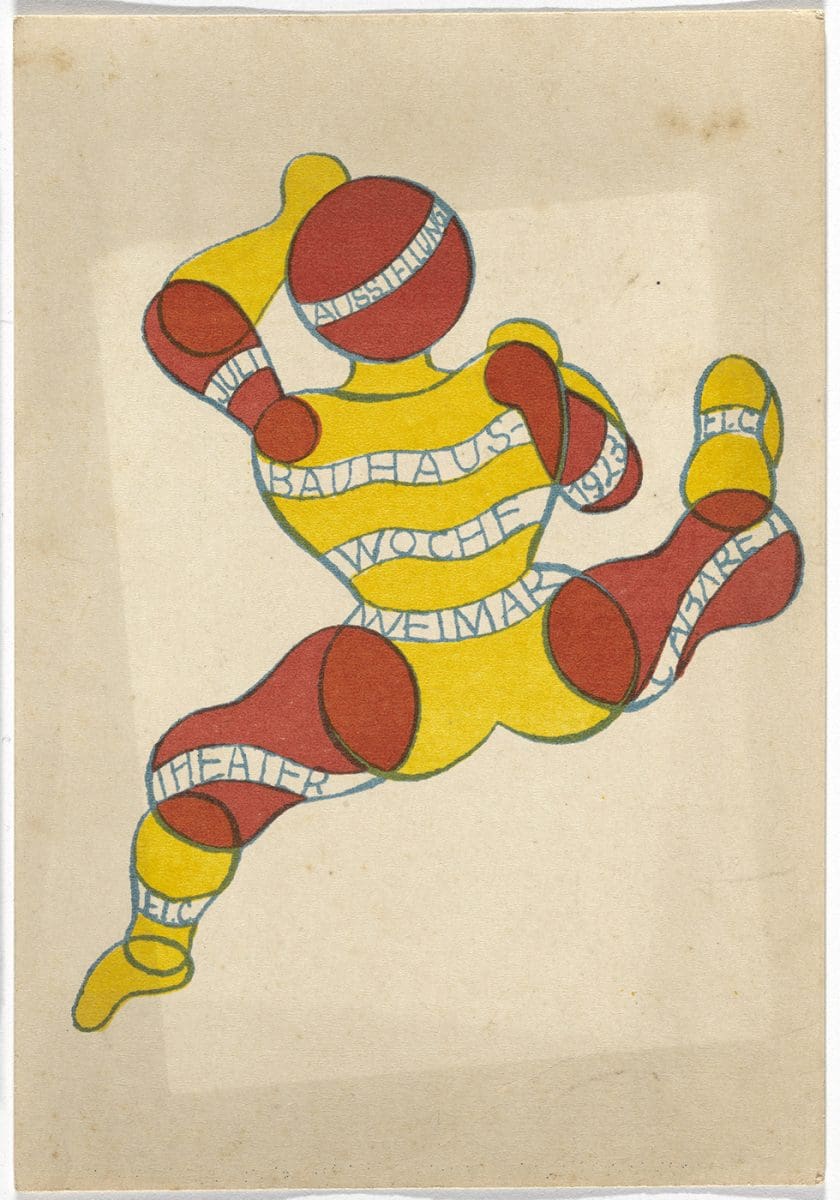

Started in 1919 in Weimar by architect Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus revolutionised the way art was taught. In uniting art, craft, industry and technology, the future-directed school re-thought art in experimental and egalitarian guises, revealing the fundamentals of forms and processes. The rise of Nazism forced many Bauhaus artists to flee Germany before the school closed in 1933. And it’s this diasporic history that is central to Bauhaus Now!

Entering the exhibition one is first greeted with the contemporary: a room of luminous, craft-like, pattern-drenched costumes and lanterns. As film documentation shows, these fantastical outfits were worn by Melbourne artists and students walking to the gallery. The journey reimagines a similar procession in Weimar in the 1920s with the intention of summoning the ghost of the Bauhaus. This gesture drifts between meaningful and performative, but ultimately it foreshadows the play of Bauhaus Now! alongside the overt ways in which legacy can be imagined.

The show truly begins with Justene Williams and Mikala Dwyer’s Mondspiel, 2019. Characterised by the artists as “part resurrection and part zombie dance,” it’s a spectacular carefully tended universe encompassing video, installation, sound and sculpture. Taking influence from the early Weimar years of the Bauhaus, the artworks fill an entire gallery room and nods towards the school’s diasporic history and occultist leanings. Yet there is no trademark minimalism here: it’s the mystical Bauhaus. In a room beaming with colour and texture, there are large magnetic and layered videos, a thistle garden on dumped soil, a coffin installation, and a colourful figure suspended high on scaffolding. While each art object is inspired by a Bauhaus artist or work (as revealed by the wall text), the influence and legacy is better felt in the spirit of the works.

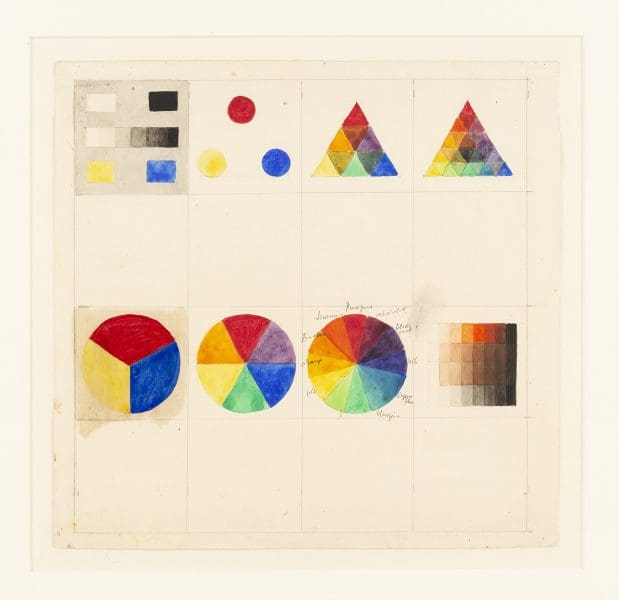

Upstairs are further contemporary pieces alongside works by the three exhibiting Bauhaus artists: Paul Klee, Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack and Gertrude Herzger-Seligmann. While Klee never migrated to Australia and has only one painting in the show (“The only Paul Klee in Australia!” I am told by two invigilators), both Hirschfeld-Mack and Herzger-Seligmann were Bauhaus students exiled to Australia during the rise of Nazism. Yet Herzger-Seligmann is a fatally fleeting presence. Her art has been lost to history, and all that exists is archival material documenting her absence (which is potentially made more absent by its placement in the corner).

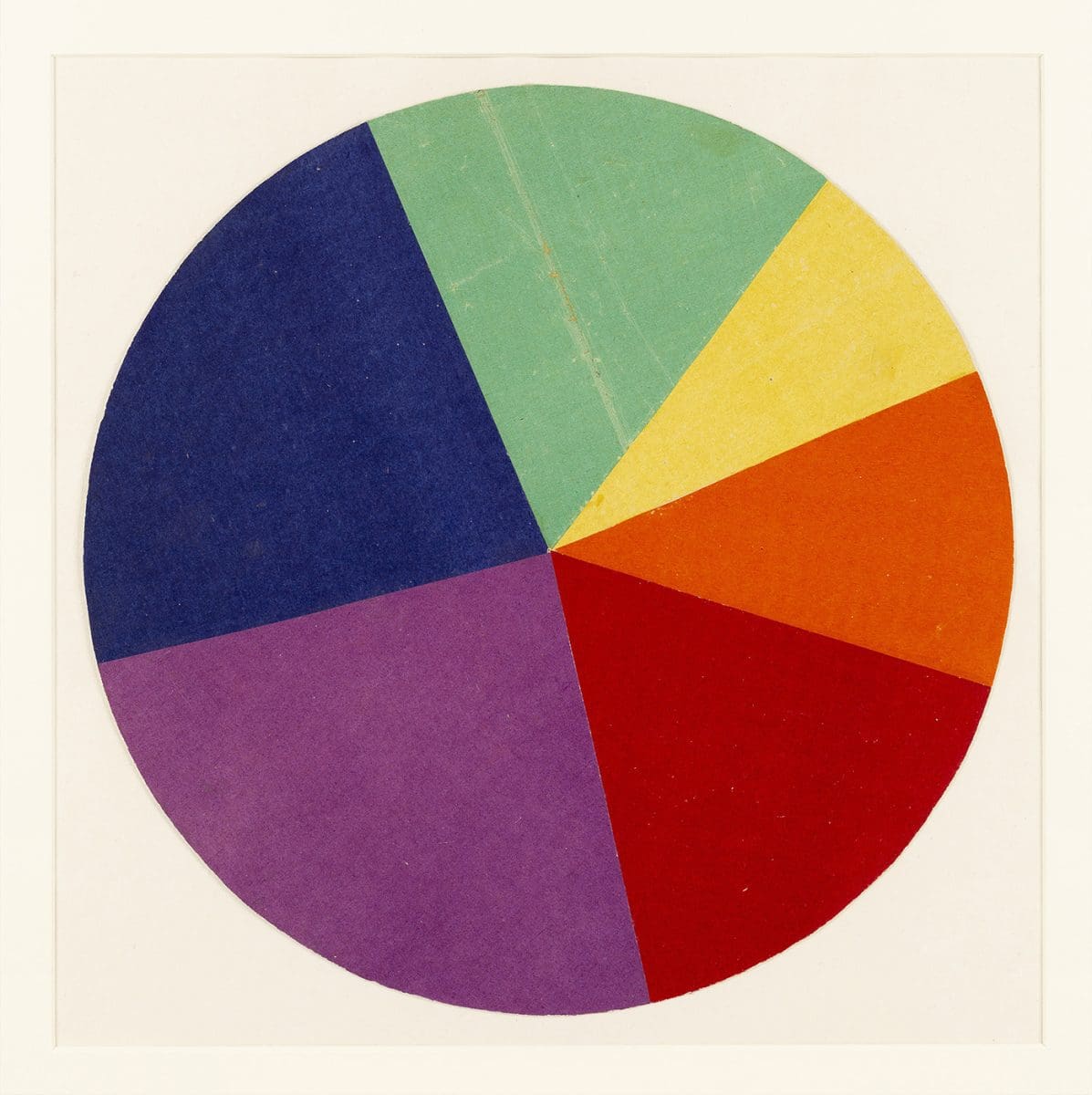

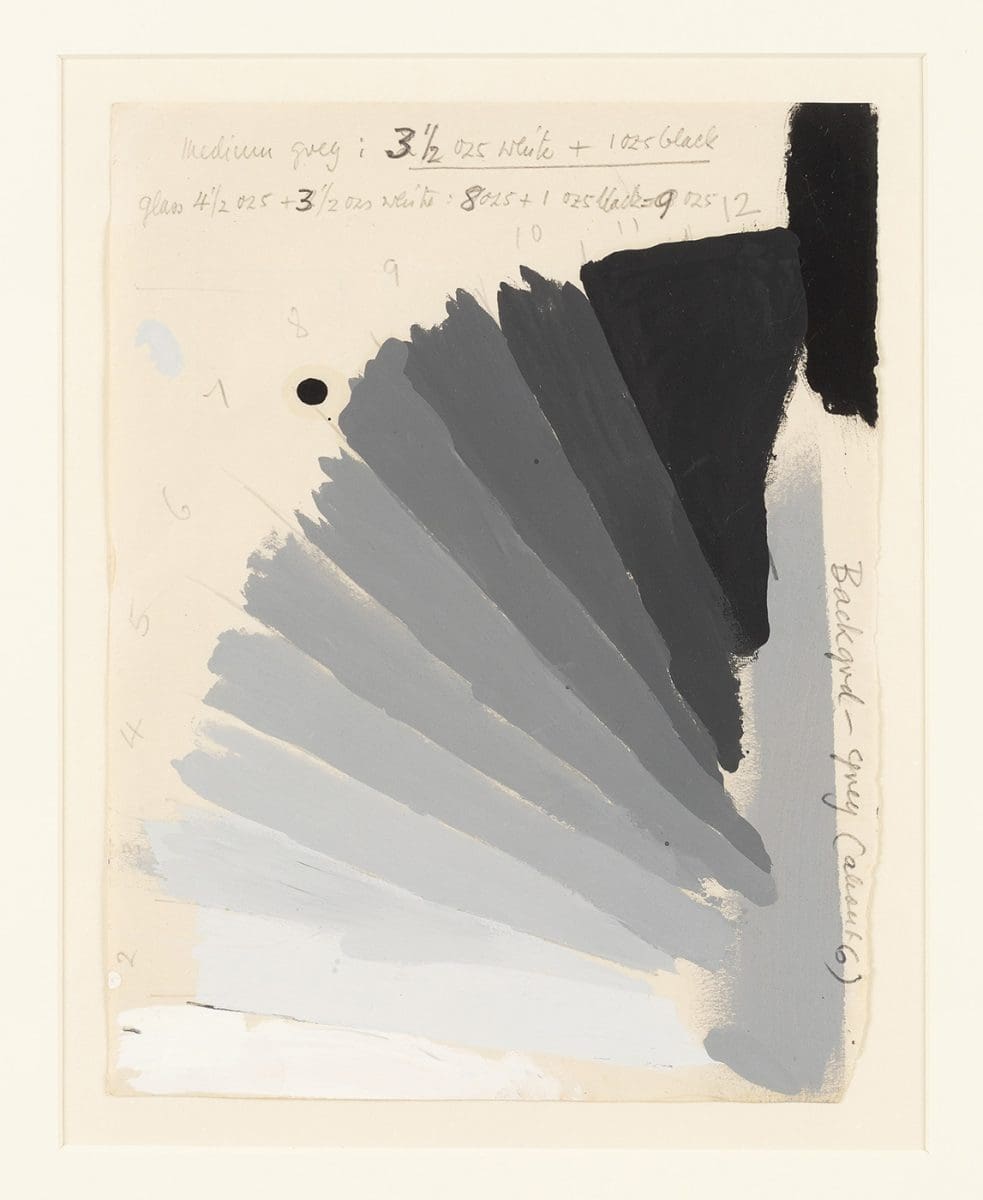

Hirschfeld-Mack becomes the main historical presence through his playful forays into colour and form. His work quietly teeters with avant-garde possibility, alongside the Bauhaus-inspired aim to rethink the teaching of art. After coming to Australia Hirschfeld-Mackbecamea teacher, and later headmaster, at Geelong Grammar and his belief in the importance of play – of learning through experience rather than being taught – exists poetically and literally throughout the exhibition.

While the contemporary pieces in Bauhaus Now! may have been influenced by (but never quite realise) the avant-garde of the Bauhaus, what feels valuable is not only the mysticism and play, but the generosity within the show. In the exhibition there is a 1950s instrument created by Hirschfeld-Mackwhich allowed socially disadvantaged children to develop “colour chords” through twelve resonating chambers. The students, now able to play via colour, needed no notational training. This one object so beautifully fits the Bauhaus remit of entwining function, design, egalitarianism, experimental education and collectivism. And above all, it feels generous.

And it’s the generosity of the Bauhaus, the way that it gave and taught art in new and exciting way, that is acknowledged and repaid through contemporary resonances.

Bauhaus Now!

Buxton Contemporary

26 July – 20 October