Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

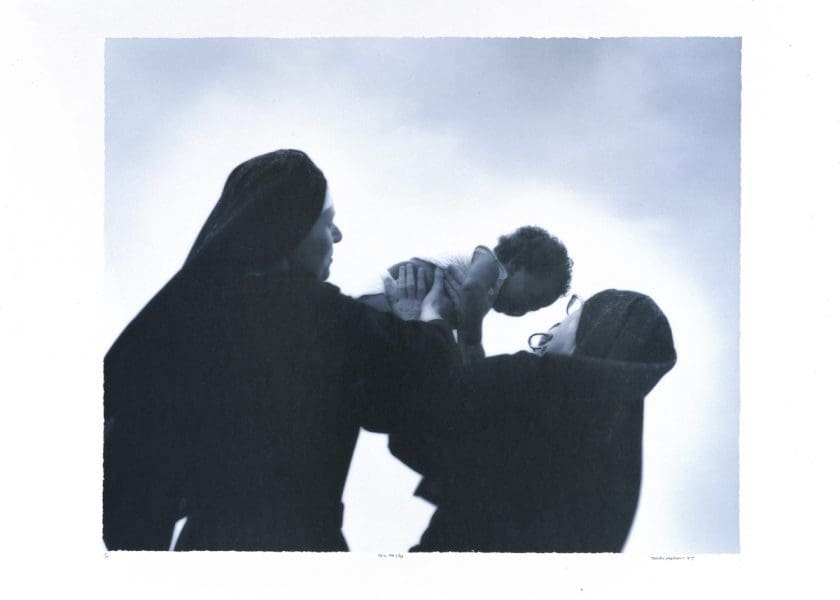

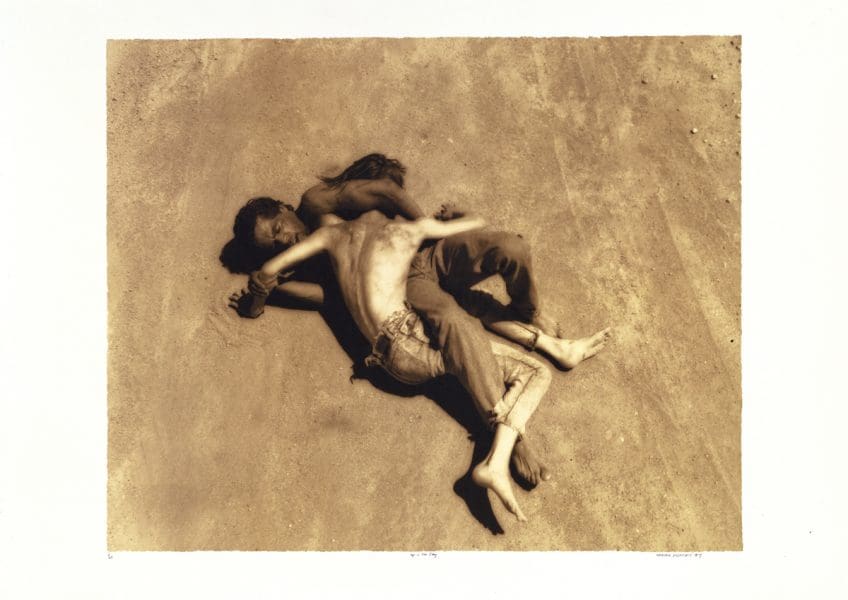

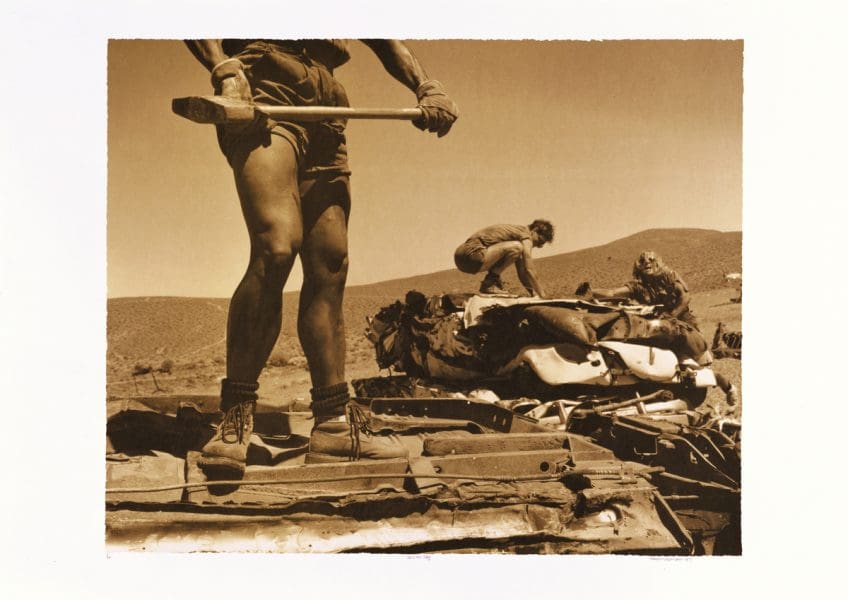

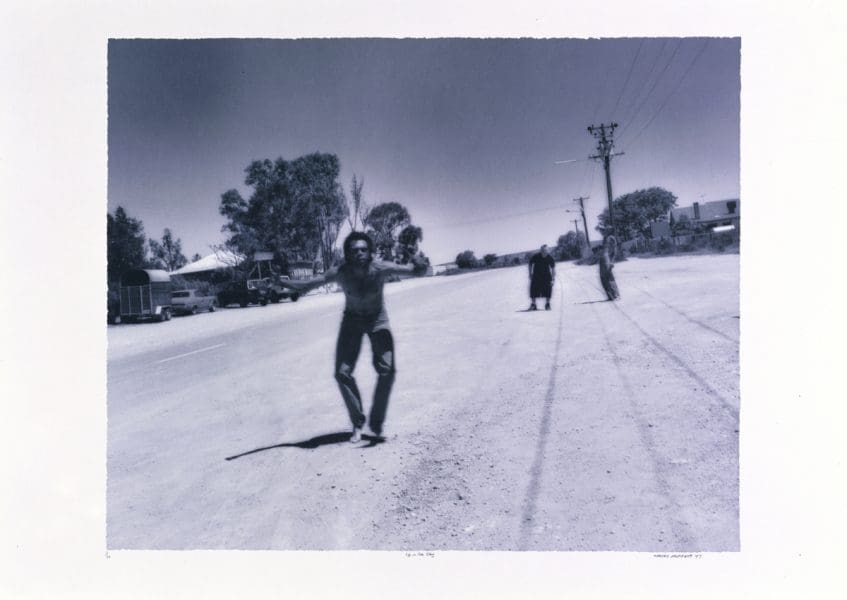

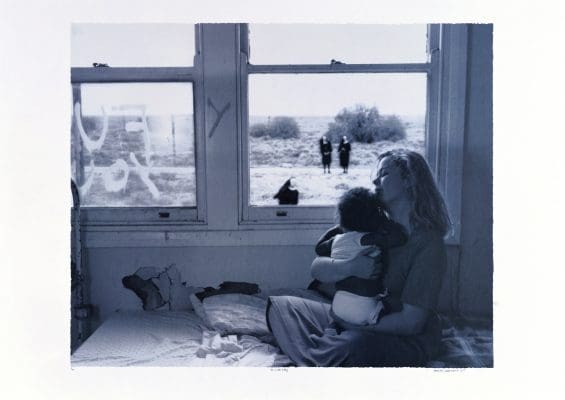

Cigdem Aydemir is one of 11 artists in Up in the Sky | Landing Points at Penrith Regional Gallery. In this exhibition the artists respond to Tracey Moffatt’s series Up In The Sky, 1997, iconic photographs that poetically and disturbingly addressed issues of race relations and cultural identity as Australia approached the millennium.

Aydemir, of Turkish-Muslim heritage, has for many years explored the artistic possibilities of the burqa and toyed with perceptions and symbolism of the garment. Earlier this year she also had the confronting experience of withdrawing a piece from the MCA after a strong reaction to her use of ‘blackface.’ Barnaby Smith spoke to Aydemir about the politics of her work, #illridewithyou, and the legacy of Tracey Moffatt.

Barnaby Smith: Can you describe the first time you came across Tracey Moffatt’s work and the impact it had on you?

Cigdem Aydemir: I’m an art teacher and I’ve shown her work to my students a lot. I’ve engaged with her work mostly in educational settings. I can’t remember the first time I came across her, but I know that at university I was drawn to Indigenous artists, as well as African-American artists.

BS: What is the process of ‘responding’ to the work of another artist, for you?

CA: I have scraps and notes all over the place. I write these little threads of ideas that just stay somewhere for a really long time, and then if I get invited to something I might see a thread between an idea I have and another artist’s work.

BS: In your work in Landing Points (The Ride, 2017) you are wearing a headscarf while ‘riding’ a stationary motorbike against a projected backdrop of the outback. How does this work relate to Moffatt’s?

CA: I didn’t make this work as a direct response to her work. That’s not how it happened. I had the idea for The Ride for many years lingering at the back of my mind, and then I did the Proximity Festival in Perth, 2017, a festival of performance art for one audience member at a time. I started exploring the idea, and thinking how I could push it in different directions.

Then I was asked about this show at Penrith in response to Tracey’s work, and it was serendipitous that this image I had of the archetypal Australian landscape converged with Moffatt’s work, which was also about that archetypal landscape but subverting that, and dealing with race relations. There were quite a few similarities, but it wasn’t as a direct result of her work that I made this one.

BS: What was the inspiration behind The Ride, as it appeared in Perth?

CA: It came during that hashtag trend #illridewithyou following the siege at the Lindt café in Sydney. I was thinking that it would be funny to flip it on its head. I didn’t know if the Muslim woman would be riding on a horse through the outback or something else, but as we started getting into it I really liked the motorbike idea because it relates to the Mad Max movies and there’s a rebellious attitude that comes with it.

BS: Yes, one of the first things that came into my head in relation to The Ride was the film Thelma and Louise. You also mention the Mad Max films, so was cultivating a cinematic sense one of your intentions with the work?

CA: Yeah absolutely. Mad Max, Thelma and Louise… There’s a cinematic quality to Tracey Moffatt’s work as well.

BS: Can you expand on the political angle and the point you were making about #illridewithyou?

CA: The hashtag campaign came after a Muslim woman in hijab was attacked on public transport, and another woman wanted to help her and that started this campaign.

What was interesting for me was that some of it had undertones of the white saviour complex and patriarchal protectionism, which is what this whole work is about. How would it feel if Muslim women were saving other people? If I said to you for instance, ‘There’s nothing for you to worry about, I’m going to look after you,’ there’s something protectionist about that. You haven’t asked for that help, yet I’m creating this dynamic between us.

Would the campaign have been received in the same way if the situation was reversed? That’s the scenario I wanted to explore.

BS: What did the performance dimension demand of you?

CA: Being a one-on-one performance, I really had to think about every little aspect because when someone is right in front of you everything you do has meaning, has depth, is read into.

From the moment the person entered I took on a persona where I was very straightforward and quite butch: this is my domain, you sit here, you do that, you do this. Yet I also gave them opportunities not to feel intimidated, it was this interesting dance between giving them breadth to be creative and enjoy the experience while also providing a dynamic that would flip #illridewithyou.

The bike actually turns on, a massive Harley Davidson starts roaring and vibrating (as if it wasn’t sexual enough). Then the fans start going and the backdrop starts moving, Midnight Oil are playing, and we ride.

I did over 100 performances, and what I’m exhibiting in Up in the Sky | Landing Points is the video documentation of that across three monitors showing 27 of those performances.

BS: You issued an apology for the blackface that was part of the MCA work I Will Always Love You, 2017. What has that episode taught you and might it make you reluctant about making certain creative decisions in the future?

CA: In some ways it has allowed me to grow as an artist, which is good.

Would I be reluctant? Because I know how sensitive it is, I wouldn’t do that particular thing again. But I don’t think it will hold me back. I would just be more sensitive about speaking to people who could provide the kind of feedback I need. In that instance, I was getting emails from people I’ve never met, saying, ‘I think this is wrong,’ but what was concerning for me was that no one was really centring an Aboriginal person’s perspective. That’s not to say they should be telling me, that’s not their responsibility.

BS: After Pauline Hanson wore a burqa in parliament in August 2017, the academic Elham Manea suggested that the burqa has become more political statement than expression of faith. To what degree is your work more about reactions to the burqa than it is about what it means for the Muslim community?

CA: My work is more complicated.

There’s autobiography and the experience of wearing the burqa, its symbolism among Muslims and Muslim women, its symbolism outside of the Muslim community, in Australian politics… for me it’s all of those things coming together, not one or the other.

But sometimes the burqa is a political statement, absolutely. It’s worn for so many reasons and all of them are valid. I also think the burqa is a symbol that reveals other things: our fear of others and our inability to cope with difference. The burqa is just the tip of the iceberg.

Up in the Sky | Landing Points

Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest

2 December – 4 March