Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

From Yawuru artist Robert Andrew’s ‘writing machines’ to Wiradjuri artist Nicole Foreshew’s clay vessels, The 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial: Ceremony honours the rituals practiced across culture, Country and community that remain embedded in First Nation people’s lives and practices today. By celebrating Indigenous artists as “radical agents”, the Triennial puts forward ceremony as an action that nourishes while also seeking change.

Including over 35 artists, with works across dance, writing, performance, painting, ceramics and architecture, curator Hetti Perkins describes how the Triennial has been conceived “to reflect the many ways in which culture can be expressed or embodied, and how ceremony in the contemporary context continues.” Since the early days of colonial occupation, various government policies have attempted to disempower Indigenous people from engaging in ceremonial practices—and so the Triennial becomes a powerful statement honouring the continuation of ceremony in its many iterations from the personal, public, celebratory and radical.

In linking the ritual of ceremony with radicalism, the Triennial has a geographical edge that cannot be ignored: the Triennial’s original home prior to touring, the National Gallery of Australia, is situated close to the Tent Embassy in Canberra. As Perkins acknowledges, “I don’t think it’s possible to present a project like this on Ngambri and Ngunnuwal country in Kamberri/Canberra without it being political, and not even possible to do anything anywhere without it being inherently political—of which, of course, the 50th anniversary of the Tent Embassy is a poignant reminder.”

Ceremony demands that we address colonisation and assert Sovereignty through art. But it also demonstrates that contemporary First Nations artists are achieving this in multiple ways. Perkins’s lifelong experience in art and activism ensures that Ceremony remains deeply activist in scope and intention while expressing this in complex ways that celebrate artistic ingenuity. Works such as the tree scarring project by Dr Matilda House and her son Paul Girrawah illustrate that protest takes place in many forms by engraving messages into living trees in the NGA sculpture garden as a permanent marker. Meanwhile artists such as Robert Fielding highlight the impact of settler occupation of Ngambri and Ngunnawal land by recreating the abandoned cars on his Country, an introduced Western object that is also reclaimed by communities as an essential way to visit family.

Further elements of ceremony and protest are evident in the work of Yarrenyty Arltere Artists, a collective who met and began working through the community hub and arts centre in the Larapinta Valley Town Camp, Alice Springs (Mparntwe). Featuring 16 artists led by fellow artist Marlene Rubuntja, the collective’s work Blak Parliament House defies typical activist expectations by grounding itself in gentleness, with bursts of colour, humour and joy. Here, brightly coloured animals are created in a hand-sewn version of Parliament House, where the communities’ voices are heard and engaged in debate. While clearly stating that change is urgently needed in Australia, the Yarrenyty Arltere Artist’s activism appears alongside a light playfulness, showing a future where the artists are their own radical agents—something that can be achieved not only by force, but with beauty and soul. As Rubuntja shares, “In my head and heart, I grew all these ideas and I started feeling well again. Now I feel like a strong woman.”

Such messages reverberate in urban artists’ work in the Triennial. SJ Norman’s Bone Library, part of a larger performance work Unsettling Suite, is an urgent commentary on invasion and the active preservation of language made by First Nations people. The performance sees him inscribe language onto the bones of sheep and cattle, which becomes a ceremonial affirmation that Indigenous languages did not die out but live on, even in the bones of “totemic colonial beasts” as he describes. Like the Yarrenyty Arltere Artists, his work displays a delicate quality and ritual sensibility. It demands solutions to settler imposition while demonstrating that activism can take multiple forms.

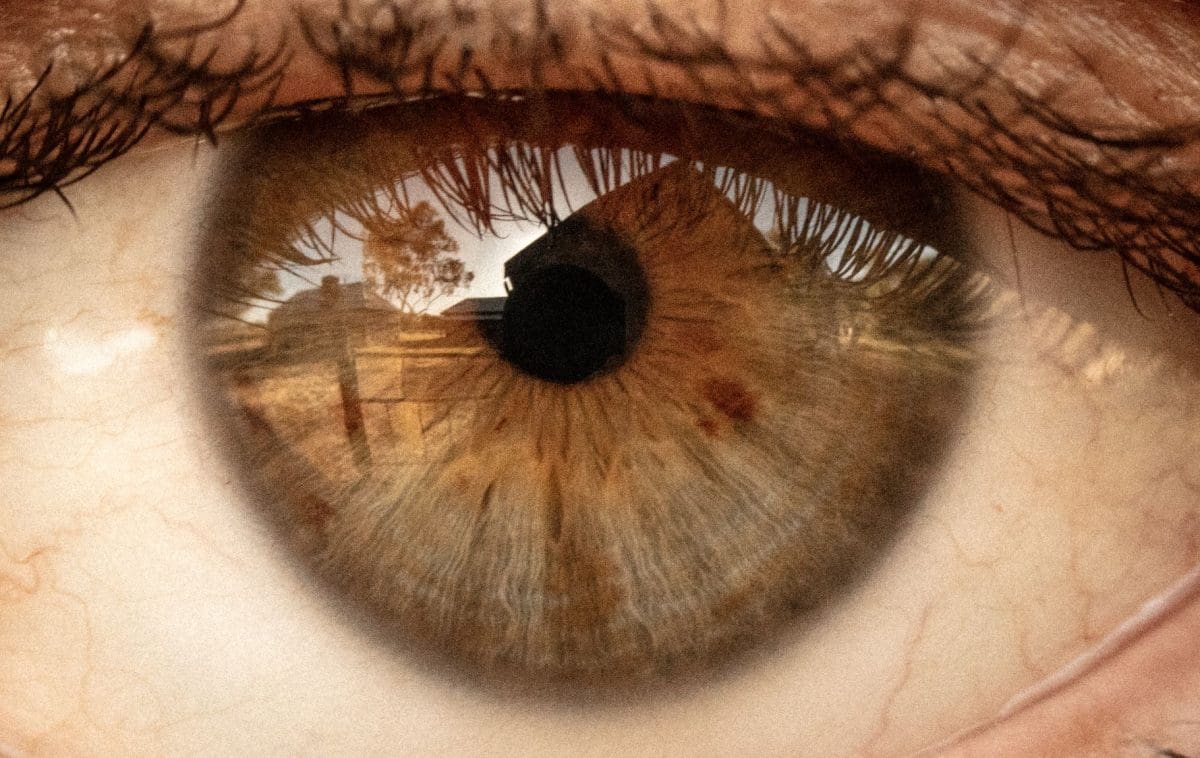

Other views of ceremony are shown through the cinematic work of Hayley Millar Baker, which draws the audience into the personal. Exhibiting her first film, the acclaimed photographer delves into her psyche and domestic sphere by creating a fictional home which acts as a symbolic entrance into her head. She describes the work as “stepping away from fixed narratives, leaving the works open to more ambiguous interpretations, but always based on some sort of truth.”

And this reveals that while truth telling remains central to Blak art, it can be expressed in intimate, evocative ways while remaining connected to wider community needs. As Perkins reflects on the exhibition at large, “Their works are at once very personal and also speak with a ‘common tongue’ or language that taps into the things we all share as Kooris/Murris/Anangu/Yapa etc etc!”

New video work by dancer Joel Bray provides hope as much as it laments the pervasive horror of colonisation. With an innovative practice in contemporary dance blending comedy, audience participation, text and live art, his new work promises to engage audiences in urgent discussions while continuing to express a unique dynamism which pushes dance into ritual protest. Perkins explained that “protests are a form of ceremony in some ways, acts of faith, processes of change, coordinated community actions with a collective outcome, or intimate expressions of belief…” And audiences will find a richer understanding of the interwoven legacy of art, ceremony and activism in this exciting Triennial.

The 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial: Ceremony

Western Plains Cultural Centre

27 January 2024–19 May 2024

This article was originally published in the March/April 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.

The 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial: Ceremony is a touring exhibition, currently on display at Western Plains Cultural Centre.