Reframing a Collection

Drawn from the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art at the University of Western Australia (UWA), Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery’s show Place Makers, reframes the artists—who just happen to be female.

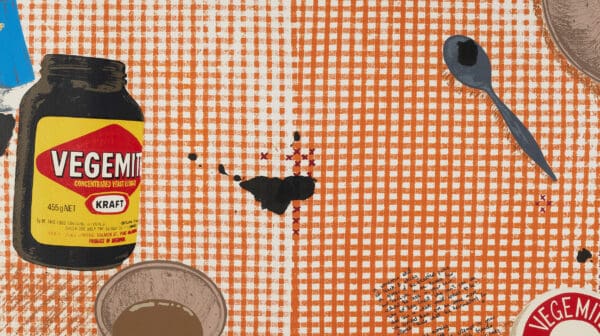

Emily Crockford, Funky Jungle Rosie in her Pom Pom Zoo, 2019, acrylic and posca on canvas, 122 x 152.5cm.

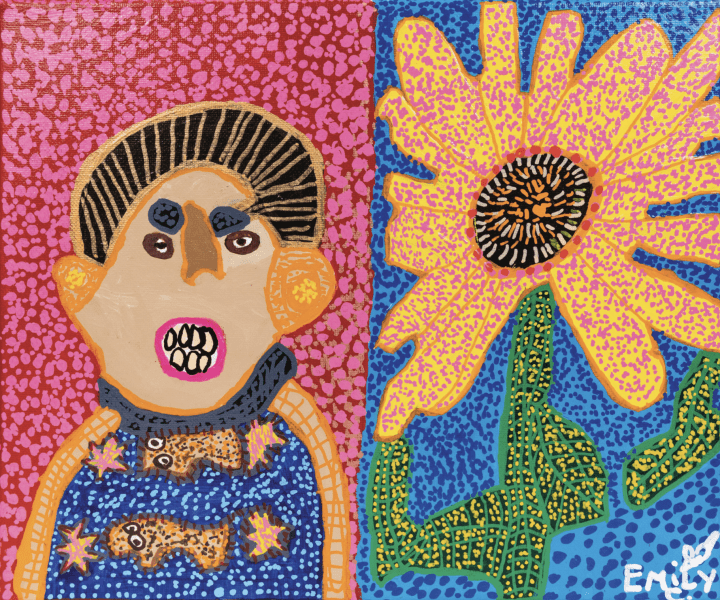

Emily Crockford, Nadia Daisy of Present. Courtesy the artist and Studio A.

Alan Constable, Not titled, 2020, earthenware; glaze, 13.5 x 23 x 21 cm. Image courtesy of Arts Project Australia.

Arts Project Australia studio. Photograph: Kate Longley.

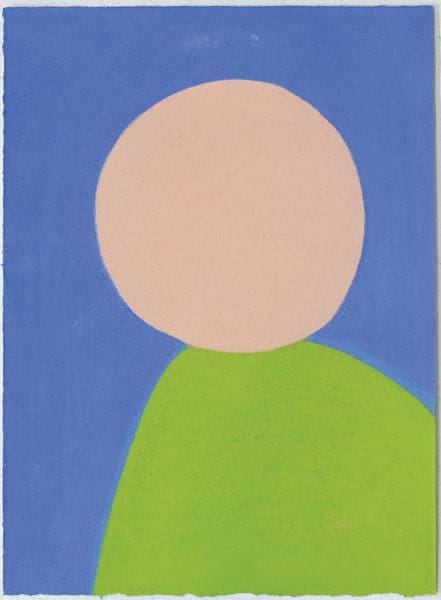

Julian Martin, Not titled, 2020, pastel on paper, 38 x 28 cm. Image courtesy of Arts Project Australia.

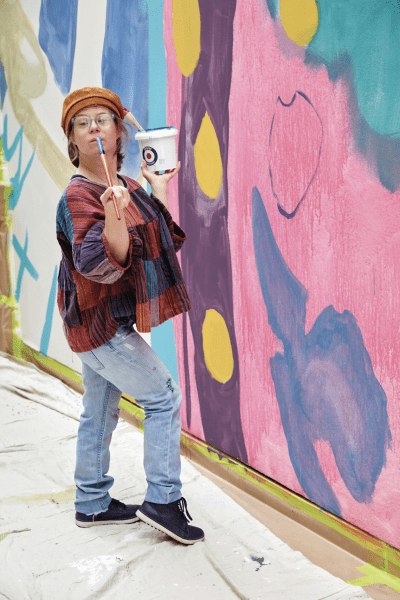

DADAA artist mentoring. Photograph: Miles Noel Photography, 2020.

Emily Crockford is at the opening of the 2019 Salon des Refusés, a long-running Archibald spin-off for portraits that weren’t selected for the official exhibition. On display is Crockford’s intricately patterned, utterly vivacious portrait of artist Rosie Deacon. “There were so many different colours and creepy creatures, like a koala sitting on a cushion,” recalls Crockford of visiting Deacon. “I saw lots of colours in her studio, like [a] rainbow, and then I painted Rosie on a big canvas.”

Titled Funky Jungle Rosie in her Pom Pom Zoo, the painting was hanging beside a podium where a respected member of Australia’s arts media was opening the exhibition. Crockford, who practices from Studio A, a Sydney-based supported studio for artists with an intellectual disability, was standing nearby. Right next to Crockford was Gabrielle Mordy, director at Studio A, who was expecting Crockford to be mentioned as an example of the exhibition’s diversity, especially with bold work ready to be gestured to. Instead, Crockford was asked to stand and wave to the audience. Would this ever happen, Mordy thought, to a neurotypical artist?

The opening speaker further positioned the painting as a collaboration between Crockford and Deacon. Like any work submitted to the Archibald, it was painted by Crockford without assistance. Where had this assumption, that it was a collaboration and not Crockford’s own work, come from? There wasn’t any maliciousness, but there was a trademark unawareness of the intersections between intellectual disability and contemporary art.

Mordy remembers thinking, “God, we’re still at this point where the challenge is still getting the work into platforms where it can be critiqued against other work.”

Despite Crockford being a respected Australian artist and a finalist in the 2020 Archibald Prize, this is one small example of the stigmas that belie artists with an intellectual disability in contemporary art. Yet we shouldn’t confuse this with a melancholic story—Australian artists with an intellectual disability exhibit widely both nationally and internationally, from artist-run spaces to commercial galleries, to major private and public collections. And the recognition goes beyond Australia: The New York Times declared the incredible, distilled pastel works of Melbournebased Julian Martin “a must see”, while renowned art critic Jerry Saltz cited Lisa Reid as a “strong voice of art” for her delicate and emotive works on paper.

And yet, despite these achievements, there are still moments in which the legitimacy of the art must be persuaded, ensuring it’s not seen as recreation or art therapy: it’s about having it appreciated as art, in and of itself.

This contemporary situation leads back to one historical phrase: ‘outsider art’. Coined in 1972 by art critic Roger Cardinal, it is the English translation of art brut, the French label meaning raw art or rough art, which was first uttered by artist Jean Dubuffet to account for art that happens outside official culture. Over the decades, the term has only served to obscure and degrade the very art it speaks of, pushing it to the periphery, and revealing the normalising tendencies of the art world.

Three of Australia’s most highly-regarded supported studios—Arts Project Australia in Melbourne, Studio A in Sydney and DADAA in Perth—do not use this label. Other small supported studios I spoke to also eschewed the banner. Today, the most neutral phrases are ‘self-taught’ and ‘outlier’ art: these aren’t perfect, but they are viewed as better alternatives to the historic labels of untrained, naïve, folk, art brut, amateur and primitive. While self-taught and outlier can’t account for the singular experience of an artist, the words often refer to creators who did not attend art school, have little to no formal art training, and who, for a variety of reasons pertaining to gender, class, race or age, have been pushed from the mainstream art world. It may also include artists with intellectual disabilities, mental health issues, migrant experiences, or a history of incarceration.

And yet, the label outsider art is still popularly used. Mordy believes it’s related to romanticising the idea of artists who live ‘outside’ the world. “I think there’s this notion that artists from supported studios exist outside culture and exist outside influence and that that’s an ideal state, and that they just have this free access to the flow of creativity,” she explains. Such ideas ignore how the artists are influenced by the canons of art history and pop culture, their lived experience and capacity to digest the world, and the aesthetic skills that they hone and develop over decades. Most insidiously, it denotes a conservative desire for an unmediated link between expressiveness and creation—it’s the thinking behind the white male genius artist, ignoring the social context of how art is created.

Art, however, is also a business. Sim Luttin, curator and gallery manager at Arts Project Australia, believes the label outsider art is also market-driven; a kind of marketing to sell self-taught art. “With so many recent social changes focusing on diversity and inclusion, to me, there doesn’t seem to be any other logical reason to propagate the term other than economic,” she says. “More and more, artists of all backgrounds and persuasions are being given access to the contemporary art world and, over time, marginalised artists will be given equal standing to their mainstream peers. So, the term outsider art is still a problematic term as it, in its most basic function, reinforces ‘otherness’ and outdated arts hierarchies.”

The dismantling of these hierarchies often begins with supported studios. Across Australia, such studios are vital to giving space, resources and support to marginalised artists. Arts Project has over 150 artists attend weekly, while DADAA has 226 artists attend each week. Staff artists work with the attending artists, but they do not teach; the staff artists support, guide, propel, suggest. The talent and skill are within the artists.

While the choice of whether to identify as an artist or as an artist with an intellectual disability is individualised, many artists from supported studios want to be known as artists first and foremost. As Crockford says, “Seeing my work up makes me feel happy and proud, I get to share a space with other artists up on the wall with me.” Ceramicist and painter Mark Smith, who practices from Arts Project, wonders about distancing the artist’s biography from the art they produce. “I don’t know if you should actually merge the two,” he says. Jordan Dymke, who also practices from Arts Project, wants “recognition for my work.” He continues, “I want to really have the same opportunities as everyone else. I know that people sugar coat disability as, ‘Oh, we should give an opportunity to that person because they have a disability.’ I don’t want that.” Supported studios and galleries take such sentiments on board, and the language when communicating to the public is very much the language of contemporary art, not community art—and this is where galleries are crucial.

One of the most important curators currently engaging with the history of self-taught art in the United States is Lynne Cooke—an Australian—who in 2018 curated the widely lauded, historically potent exhibition Outliers and American Vanguard Art at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Outlier and selftaught art, writes Cooke in the catalogue, is a “field whose history has been fundamentally shaped by exhibitions,” with the implied message that curating and exhibiting is fundamental to appreciating outlier art as art. The United States is ahead of Australia in this appreciation.

Yet artists with an intellectual disability can have difficulty accessing these platforms, which is why the galleries that accompany supported studios, like those at Arts Project and DADAA, are critical sites where the work is exhibited and made public. The next step is exhibiting at commercial and public galleries and museums. “I think part of the problem is the challenge to get the work into the landscapes where those people are seeing work,” says Mordy. She explains that many institutional curators find emerging talent in artist-run spaces and smaller commercial galleries, and part of Mordy’s mission is to position Studio A artists in these spaces, as well as prizes such as the Archibald. The aim is to have the work critically engaged with, and to be selected alongside neurotypical artists’ work.

Arts Project, which is one of the top supported studios in the world, has a similar remit. Arts Project artists exhibit in galleries ranging from local artist-run spaces all the way up to international representation with respected commercial gallerists like Fleisher/Ollman in Philadelphia and Sonia Dutton in New York—as well as showing at spaces such as The Outsider Art Fair in New York, the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) and National Gallery of Australia (NGA). In March 2021, Arts Project opened a new gallery space in Melbourne’s art precinct Collingwood Yards—importantly positioning the gallery within contemporary art peers, not solely within disability.

Many Arts Project artists have high profiles, such as Alan Constable, who has practiced from Arts Project for 30 years, creating renowned ceramic cameras. He now sells the majority of his work internationally. As NGV curator David Hurlston brilliantly summed up in a video on Constable, “One of the things that sometimes I find grates a little bit is the term ‘outsider art’. I know it’s used quite widely in terms of art-historical speak and the way curators talk, but I think that when we’re looking at people like Alan Constable, his work is the work of a contemporary artist, and I think his work should be seen in that way.”

Fostering such relationships with esteemed curators is central, as are wider partnerships for supported studios and galleries. At a practical level this involves government and disability services, but it also involves partnerships with cultural institutions, dedicated philanthropists, art world influencers, curators and neurotypical artists.

Some critics have argued that self-taught artists represent a challenge to art institutions and conventional modes of curating. This is somewhat true, but it’s also important to remember that self-taught art is often ignored by institutions altogether. In a recent Art Guide podcast series I produced called FEM-aFFINITY, which builds upon an exhibition of the same title that brings together neurodiverse and neurotypical female artists, I spoke with art historian Anne Marsh who concurred that outlier art has been entirely ignored by art institutions and that change, while slow, is also inevitable. David Doyle, director of DADAA, agrees, adding, “There’s a real interest in the diversity that arts and disability practice bring to our broader cultural landscape. Certainly 26 years ago that was a battle, but I think the whole diversity agenda has really helped change that.”

It was only in 1986 that Australia first developed the Disability Discrimination Act, and around this time there was mass de-institutionalisation in Australia. “Previous to that there was a huge invisibility for people with a disability in Australia because they were institutionalised and there weren’t those sorts of mechanisms and policies like the National Disability Arts Strategy,” explains Doyle. “There was no funding that an artist with a disability could directly and easily apply for. Policy has played a significant role in the growth of arts and disability in Australia.”

This increase in visibility is also tied to media, and writing about self-taught art in critical, profound ways. “Our challenge has been for the work to be written about at all,” says Mordy. “There’s writing on self-taught art,” she says, “but there’s not necessarily writing on the work itself and how it fits broader cultural themes.”

While many self-taught artists may hesitate or be unable to articulate the reasoning behind their works (and this is something neurotypical artists also struggle with), there’s little external discussion on the art-historical value of the work. “That’s more the job of the historian or the critic to help to position it,” says Mordy. When this isn’t happening, it means that an entire field of Australian art is not getting historicised, critiqued and contextualised.

Over the decades, a severe lack of critical curating and writing on self-taught art in Australia has pushed entire creative worlds to the periphery. In 2017 the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) opened The Museum of Everything, an exhibition of self-taught art from across the world. Yet rather than reflecting on what was a highly affective, emotive, diverse exhibition, writers instead gravitated towards the showmanship of James Brett, director of The Museum of Everything. This may be valid, but it also discounted the art, and was likely safer conversation: there is no real critical or affective history of this kind of creating in Australia to draw upon.

And when critical writing does take place, it often centres upon the supported studio as a whole, rather than the individual work of an artist (this is a common exhibiting problem too). A new international digital publishing platform called Art et al is trying to address this. Launching in April 2021, it brings together platforms, writers and curators from the United Kingdom, Europe and Australia to commission critical writing on the work of self-taught and outlier artists in continental camaraderie: all of the aforementioned issues are felt beyond Australia.

Yet things are changing. In the last few years major universities have begun undertaking expansive research in this field; there is a growing movement of young, vocal artists looking at agency and intersectionality as it pertains to arts and disability; and curators and institutions are beginning, albeit slowly, to curate self-taught art into high-level exhibitions.

This is not merely an art-historical task, but also a moral one: without conjuring new levels of intellectual and emotional engagement to view and understand self-taught art, we risk losing all kinds of aesthetic understandings, thoughts and imaginations.

4 x 4 Artist Solos

Rebecca Scibilia, Samraing Chea, Monica Lazzari and James MacSporran

Arts Project Australia Gallery

15 May—26 June

The Bowling Alley

Charlie Paganin, Trinity Williams and Declan White

DADAA

21 May–17 July

This article was originally published in the May/June 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.