Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

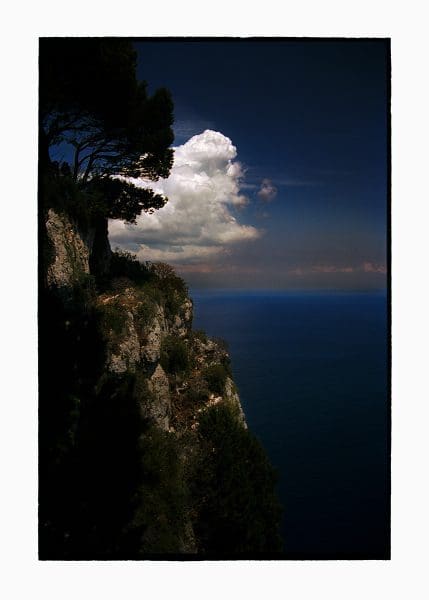

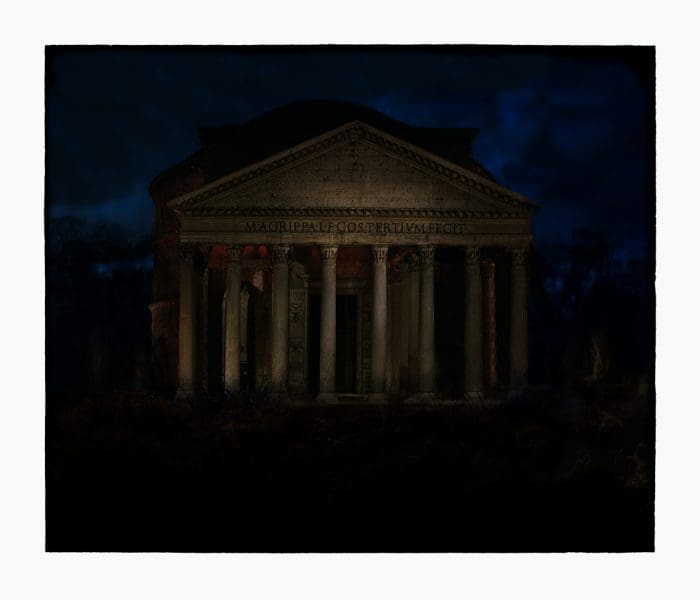

As the lift doors open on Tolarno Galleries, where Bill Henson’s latest collection of untitled photographs is currently on display, the subdued temple-like atmosphere is immediately affecting. It encourages a distinct downward-shift in gear from the bustle and blare of the street below. The blinds are drawn. The polished black surface of the floor is like an extension of a dark body of water, which passes beneath the detail of an ancient bridge depicted in a landscape on the first west wall. These artworks, arranged in flowing sequence, continue Henson’s interest in ambiguity and moments of transition; they both allude to and attempt to lengthen what he called in his 2010 Melbourne Art Foundation Lecture “the vast backward shadow of art.”

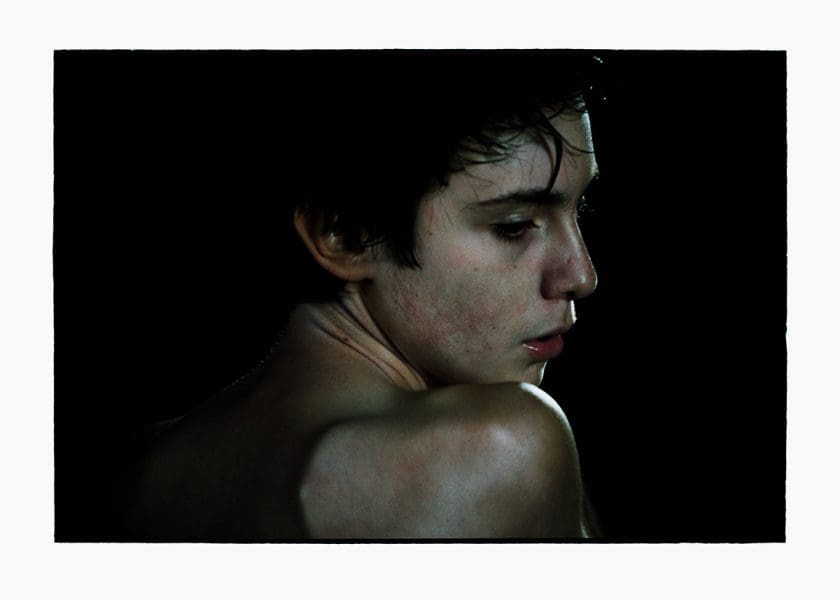

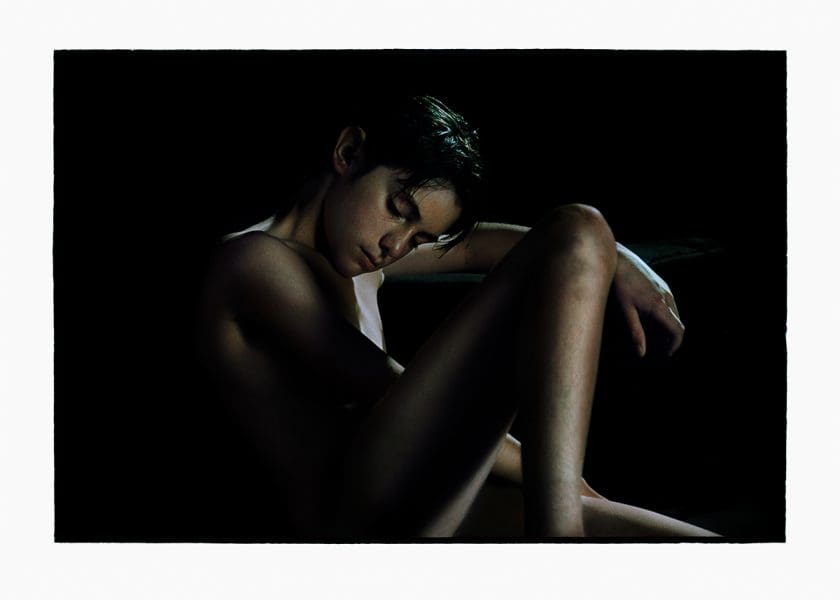

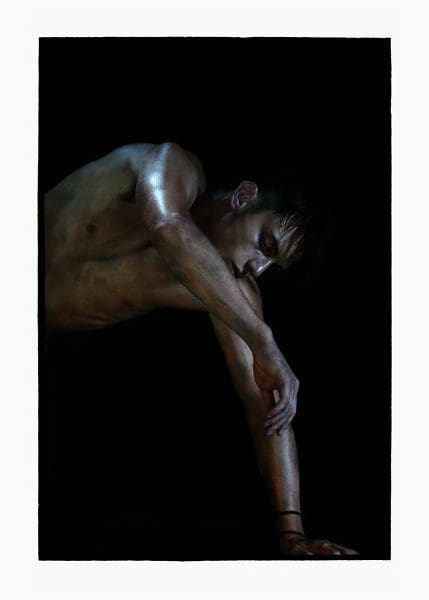

Isolated figures, with eyes cast downward (or inward), echo the postures and substance of classical Greek sculptures and Renaissance paintings while elegiac landscapes reveal fragments of beautiful ruins – great feats of the human mind and body – set against dramatic skies and deepening shadows. In four of the six photographs which feature models, attention is drawn back from the striking composition of a gesture or pose to the surface of the skin, where strange but subtle scarifying marks provide further evidence of the artist’s hands-on process. The marks, incongruous with the idea of flesh, lend the subject a sense of greater remove evoking the hard and mottled surface of marble. For me, this transformation of skin to stone resembles an entombment, linking the photograph’s subject to a condition of photography itself.

In at least two there is the overt suggestion of a soundtrack; young men appear suspended and absorbed in graceful movement. I am reminded of Geoff Dyer’s short essay “Ecce Homo,” which he wrote after a summer spent contemplating statues near the Louvre in the Jardin des Tuileries, and recognised that “photographs of sport replicate gestures from the art from the past”. This idea overlaps with what Henson called in a recent talk he delivered at ACCA “millennial slippage” which for him describes the experience of time seeming to cease or collapse as art of the past infuses or heightens moments within one’s own experience.

Few details are given beyond the information portrayed in the images themselves. The locations represented in the landscapes, although recognisable, are unnamed. They encompass a multitude of shades, and at times a patch of sky summons the pointillist detail of a Seurat, or the grainy still from an epic film enlarged. The actual location is never so important as the experience its representation conjures for the viewer as it is encountered on the walls of the gallery, and within the imagination. Similarly, the people we see are not knowable, but we recognise the intimacy contained in their gestures.

The date spans attributed to each of the artworks reveal long periods of gestation. At ACCA, in describing his method of working with models he says, “My business is about slowing them down.” He is interested in guiding them to a state of contemplation, in capturing the moment where the “smallest gesture becomes momentous.”

In this latest exhibition, Henson similarly guides the viewer to stillness. He likens the shadows in his photographs to the silences between notes in great interpretations of musical masterpieces. The darkness animates the viewer’s imagination. And although anxiety or unease will remain present for some (his approach and frame of reference remain consistent) this moment of encounter feels far from the furore of past controversies surrounding his portrayal of pubescent bodies. Rather, the mass of these 14 photographs feels like a hymn to civilised reflection.

Bill Henson

Tolarno Galleries

3 May – 2 June