“I loved them; I thought these were beautiful objects that had people on them who were in my life,” he says. “These were treasures to me; I loved the storybooks with little Aboriginal characters. They appealed to me from a very innocent perspective.”

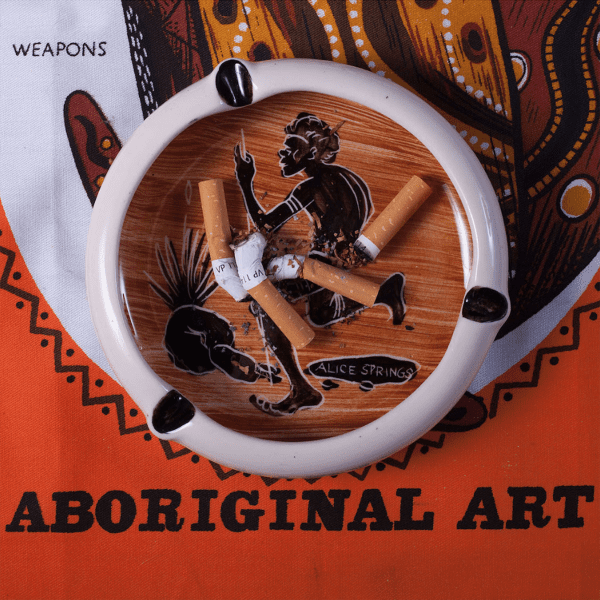

The images, drawn by non-Aboriginal people, were naive about Aboriginal lives, but not ill-intentioned, Albert believes, even as the books, comics, plates, cups, saucers and ashtrays were pressed into a more broadly problematic schema of racial politics.

Brownie Downing’s Tinka storybooks and porcelain plates, for instance, depicting an Aboriginal boy character, “were very much this love affair with the magic of the bush, like May Gibbs’s gumnut babies; the mystical notion of the Australian outback. I don’t think [Downing’s Tinka] was done with the idea of how problematic it is”.

When Albert exhibits outside Australia, many of his works take on a different meaning. His photos of teenage boys with targets painted on their chests, for instance, are, in the US, seen not as metaphorical representations of Indigenous Australian youths shot by police in a stolen car in Kings Cross, or the remote communities intervention targeting Aboriginal men.

Instead, the works are seen in the context of the African American movement that formed in the aftermath of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin’s fatal shooting by a white man in 2012: that Black Lives Matter.