Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

A friend in locked-down Melbourne recently described her sense of losing touch with reality. After restrictions finally eased to allow sitting down in public in groups of two to five, she sat in a park for the first time in months. It was a warm afternoon, and her group of two to five people was surrounded by dozens of other groups of two to five people, all identically masked up, dotted evenly across the grass. In this Bizarro-World version of a familiar reality she caught herself wondering if she’d fallen into the Sims, the other park-goers nothing more than cut-and-pasted bits of code.

This sense of the uncanny – of elaborate constructions and repeated parts pieced together almost-but-not-quite-seamlessly – echoes through many of the works in Real Worlds: Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial 2020. The exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), which is held in alternate years to the Dobell Drawing Prize, features eight artists who build immersive spaces through drawing, frequently enticing the viewer with finely-rendered detail in order to reveal unsettling twists.

“The real world is multifaceted, multi-layered, contested,” curator Anne Ryan says of her approach to assembling the exhibition. “It has many different ways of being comprehended; it has many different ways of being understood. I think that’s the thread that ties these artists together.”

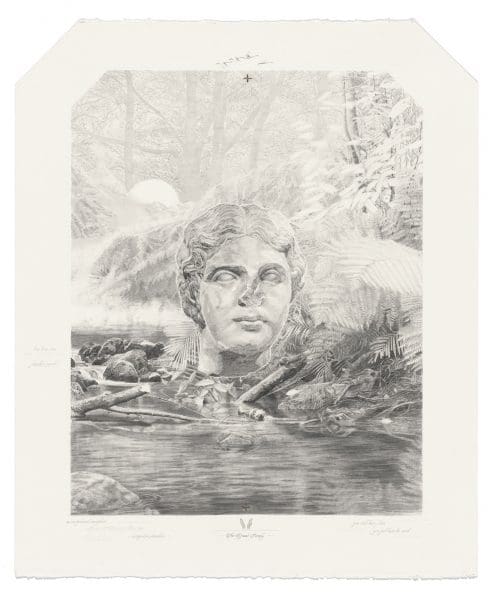

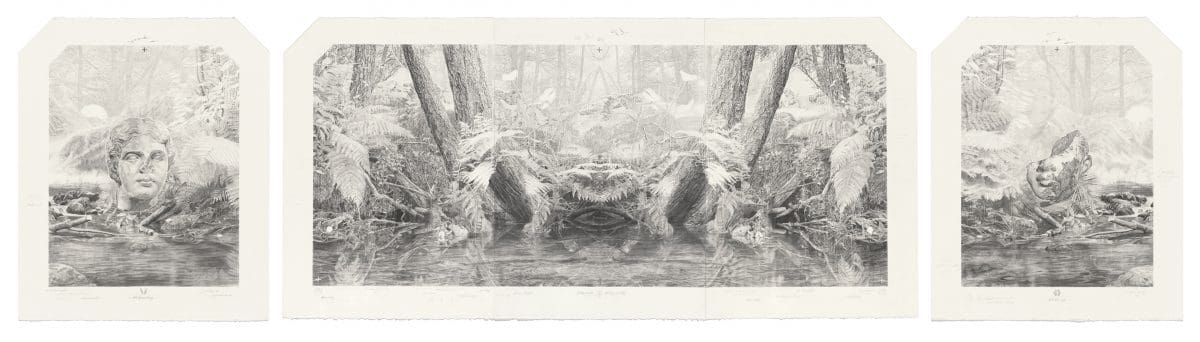

Becc Orszag’s triptych Fantasy of virtue / All things and nothing, 2018-2020,is a meticulous graphite drawing of lush scenery, resembling a 19th century Romantic landscape that, on closer inspection, is impossibly symmetrical. “Her work is very much about the idea of the human quest for utopias,” Ryan explains, “and our yearning for something better.” This scenery is flanked by two broken antique busts, disappearing into the landscape, suggesting that “civilisations rise and fall, but nature remains.”

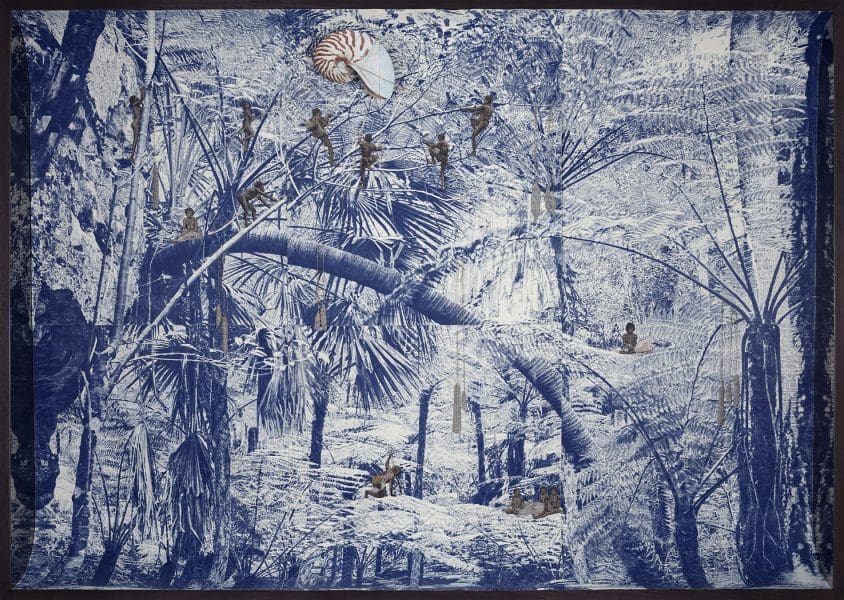

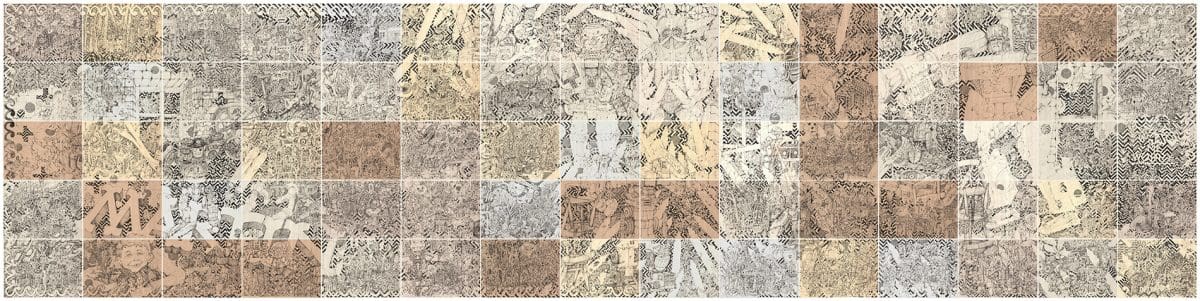

The myths and archetypes of civilisations past and present are also articulated through Martin Bell’s Martin Son of the Universe, what me worry, a complex landscape inhabited by children’s toys and cartoon characters. Inked across 75 pieces of paper, the monumental 11-metre work explores the artist’s fascination with imaginative play and storytelling, and our human need for narratives.

Making sense of things in a different way, Helen Wright’s drawings are vast, tightly-rendered accumulations of mechanical objects, piled up or imploding. Ryan speaks of Wright’s drawings “in terms of systems and organisations and structures and governments – how we all cohere – kind of falling apart because one element gets taken out and the whole thing collapses.” She adds: “They feel very, very apposite for the moment we’re in.”

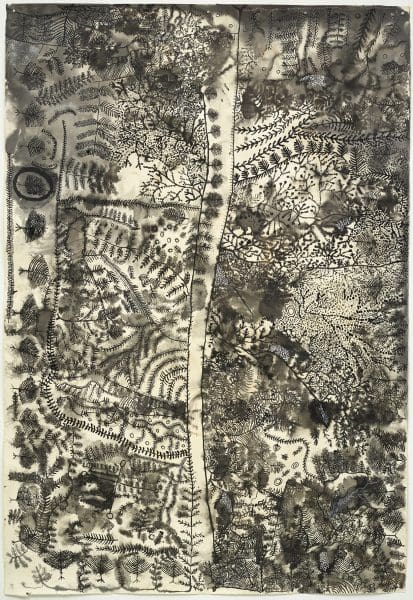

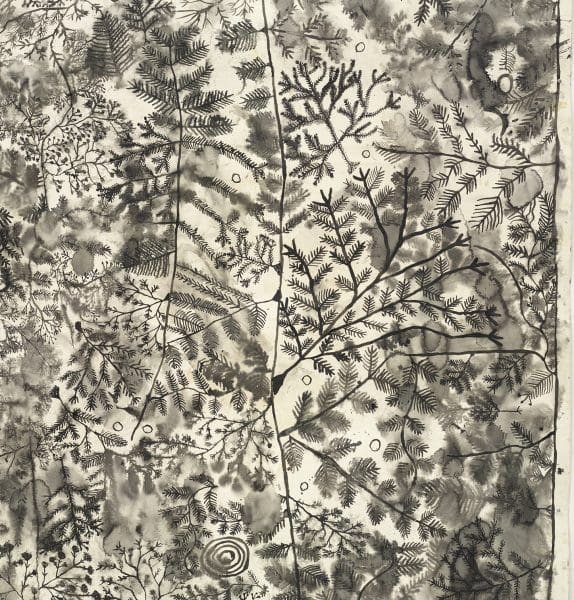

While some artists collage together elements of the ‘real world’ into slippery new arrangements, others are rooted in the complexity of solid ground. Peter Mungkuri OAM, a highly-acclaimed artist and Yankunytjatjara elder, makes exquisite black and white drawings of his Country in ink. With fluid marks, from soft washes to fine repetitions, the works convey both a sense of vast landscape and specific useful knowledge. These are, as Ryan explains, “his way of caring for Country – communicating all the important features for the generations that come after him.”

In an increasingly topsy-turvy reality, the direct approach of drawing is likely to resonate. As Ryan points out, referring not only to drawing but to the urge to classify, record, map, make sense of the world, “This is something human beings have been trying to do forever.”

Real Worlds: Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial 2020

Lake Macquarie Museum of Art and Culture

15 May – 18 July 2021