In the catalogue essay for Queer Territory at Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA), curator Maurice O’Riordan notes that “in a queer world there would be no need for a Queer Territory exhibition to claim space for [queer] artistic talent.” Unfortunately, the world we move through doesn’t always celebrate queerness—a fact exemplified by the lack of prior survey exhibitions on queer practice within the Northern Territory, and the impetus for O’Riordan to curate this show.

Queer Territory draws together diverse works from the 1980s to the present day and functions as a snapshot, rather than a forensic survey. Noting that not all artists identify with the label queer, O’Riordan is not pigeon-holing anyone, but rather suggests that there are a multitude of ways to be queer. While all artists in the show identify as queer, not all make work about being queer. Some produce vocal reflections on queer life. Others are simply queer artists, making work.

Darwin is a transient place. O’Riordan explains, “some of the artists no longer live in the Territory. They were here long enough to make a mark. The exhibition reflects the community in this sense. People come and go and add to the culture.” Despite this transience, impacts from meaningful connections in the NT community are strong. From my experience, this is reflective of being queer. I’ve found queer community to be robust and inclusive, built on inter-generational exchange and a special type of generosity courtesy of older generations. The opening of Queer Territory, which took place the night before I spoke with O’Riordan, reflected this. Artist Gary Lee gave a Welcome to Country on behalf of the Larrakia people and then handed the mic to long-term friend Chips Mackinolty, who was part of the 78ers involved in initiating the first Mardi Gras in Sydney in 1978. The crowd was made up, in part, of younger queer people and artists. O’Riordan noted it felt like an “acknowledgement of paying respect and dues to older generations. An exhibition like this can give queer community a sense that queer people are part of this world in a multitude of ways.”

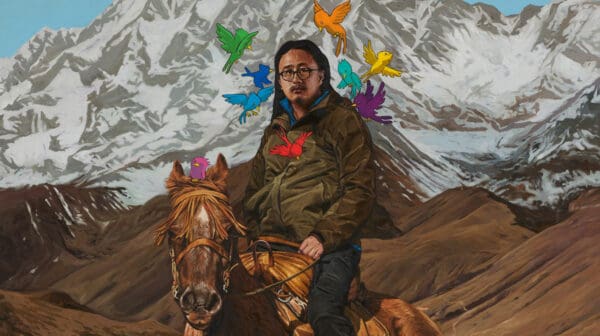

The exhibition sprang from research O’Riordan had undertaken for books celebrating the respective practices of two senior artists in the exhibition: Heat: Gary Lee, Selected texts, art & anthropology, and Candid enigma, a book detailing the life and work of late artist, and dear friend to O’Riordan, Andrew (Andy) Hau Ewing. Sitting parallel to these seminal texts, a key work is Gary Lee’s Gay Aboriginal flag (2025). In the 1980s Lee created the flag to adorn the first Indigenous float at Sydney’s Mardi Gras, after gaining permission from flag designer Harold Thomas. Lee re-created a fabric banner version for Queer Territory. The work has become emblematic of the exhibition. From the seminal experiences of these key senior practitioners, O’Riordan built a curatorial framework, allowing younger artists to draw inspiration from their forbearers. One direct example of the importance of intergenerational exchange is through the work of Elliot Hughes, who presents a series of club portraits—photographic documents of contemporary queer experience. As an emerging artist, Hughes sought advice from Therese Ritchie, one of the more established artists, who assisted with proofing Hughes’ work.

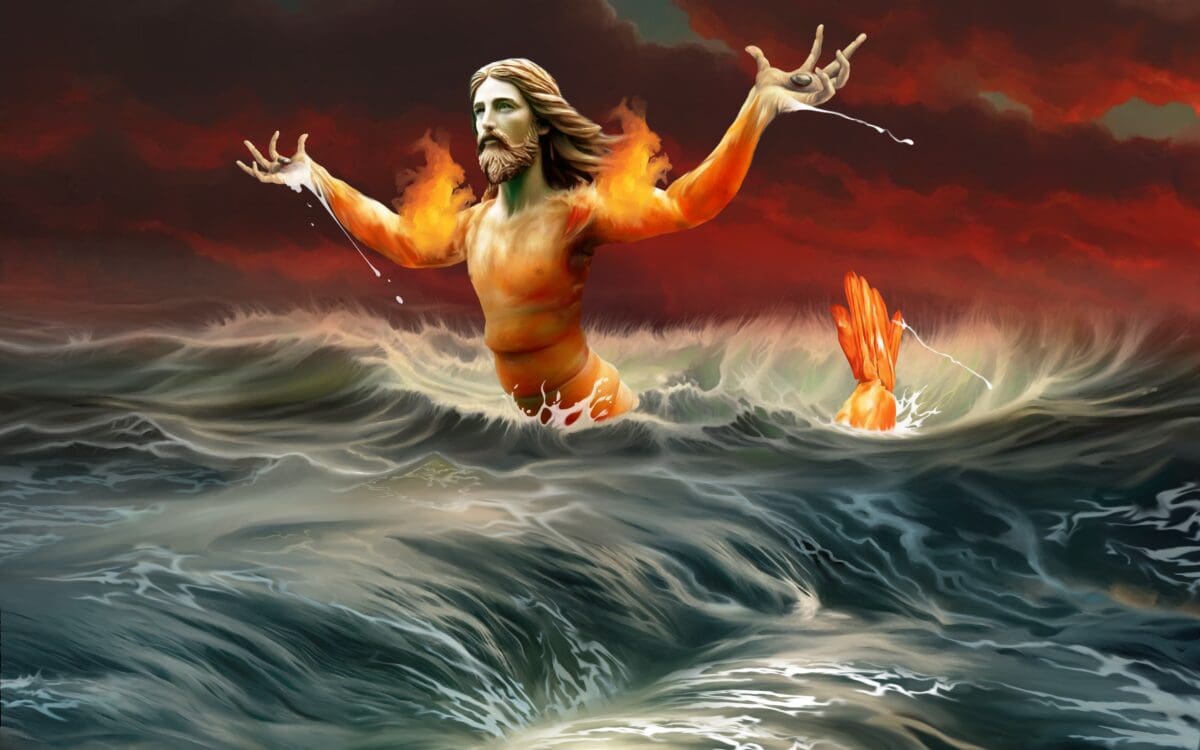

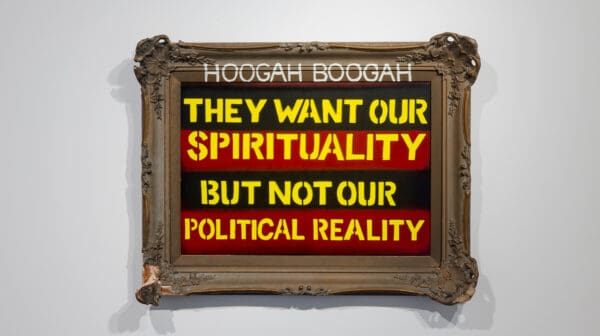

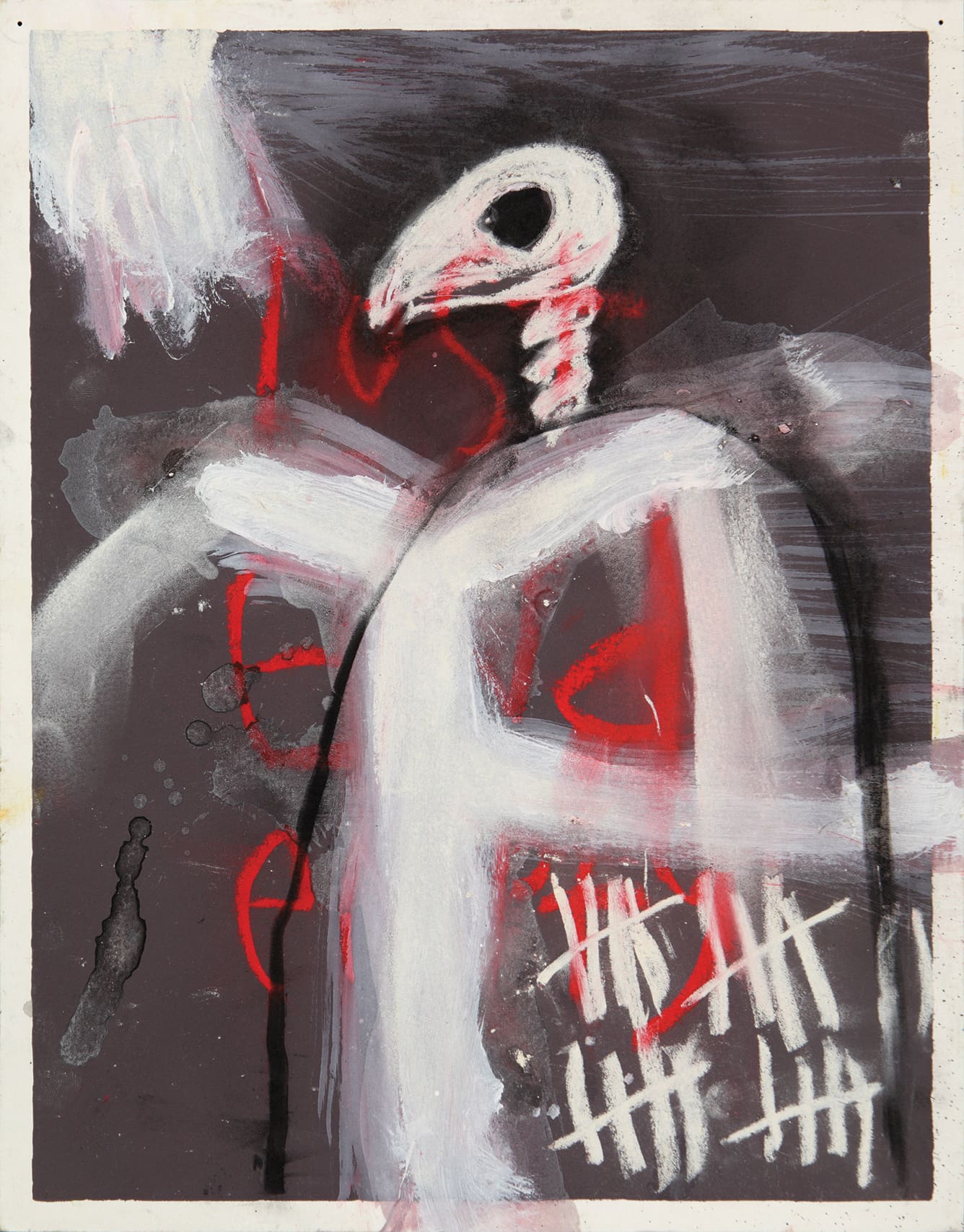

Much of Ritchie’s multidisciplinary work, including recently produced AI digital images, can be seen as social and political commentaries of life in the Territory and beyond, often reflections on inequality and racism. Echoing the religious motifs of Dino Hodge’s Ill at ease (1986), Ritchie presents Shrimp Jesus (2025)—a half-shrimp, half-Jesus figure, sailing through the open sea, aflame. Through the inclusion of Ritchie’s tongue-in-cheek reinterpretation of the icon, and Hodge’s crucifix-shaped mixed media work, showing repeated images of a naked man aside religious cards, Queer Territory positions the viewer to reflect on the impacts of religion on varied queer experiences.

Other works by artists who reposition queerness within a First Nations context include a bark painting created circa 2016 by Tiwi/Larrakia artist Nicola Miller Mungatopi, and a large banner-like work displaying the phrase “Kalu Garajini Kalu Gindigi Kunawini / Stop Gas Drilling Sell Your Fart”, created by the Yangamini collective, comprised of Crystal Love Johnson Kerinauia, Francis Jules Kapijiyi Orsto, Ainsley Kerinauia, Nadine Lee and Jens ‘Johnita’ Cheung. O’Riordan describes Mungatopi’s work as, “a classical example of Tiwi bark painting, from a proud Tiwi sister-girl” and explains that Yangamini (named for a Tiwi object-throwing game) “is a collective that promotes Tiwi sister-girls as agents of cultural and ecological sustainability.”

Andrew Ewing’s Carry (2015), the hero image of the show, and a work originally from O’Riordan’s personal collection, presents one figure piggy-backing another in a gesture of support and care. This work can be seen as reflective of lives of all the exhibiting artists, where care has been central to queer experience and artmaking. In O’Riordan’s words, “The intention of Queer Territory is to celebrate queer achievement and queer excellence.”

Queer Territory

Northern Centre for Contemporary Art

Until 12 July