Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

If showing in an international biennale is a dream job for most young artists, then Nicole Wong, a recent graduate from the UK’s Nottingham University, has already ticked that box. After several solo exhibitions in her native Hong Kong, in late 2016 a mini-survey of her work titled Day In, Day Out was exhibited in London. This year curator Mami Kataoka selected Wong for inclusion in the 21st Biennale of Sydney: Superposition: Equilibrium and Engagement.

A selection of Wong’s understated, minimal works is on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art. The artist presents three black-and-white drawings on paper and a series of six carved marble sculptures. Wong’s emerging practice has focused on making personal some of the lasting universal themes of art: time, memory and mortality. However, as the tabs on her website indicate, Wong also has a penchant for puns, poems and problems.

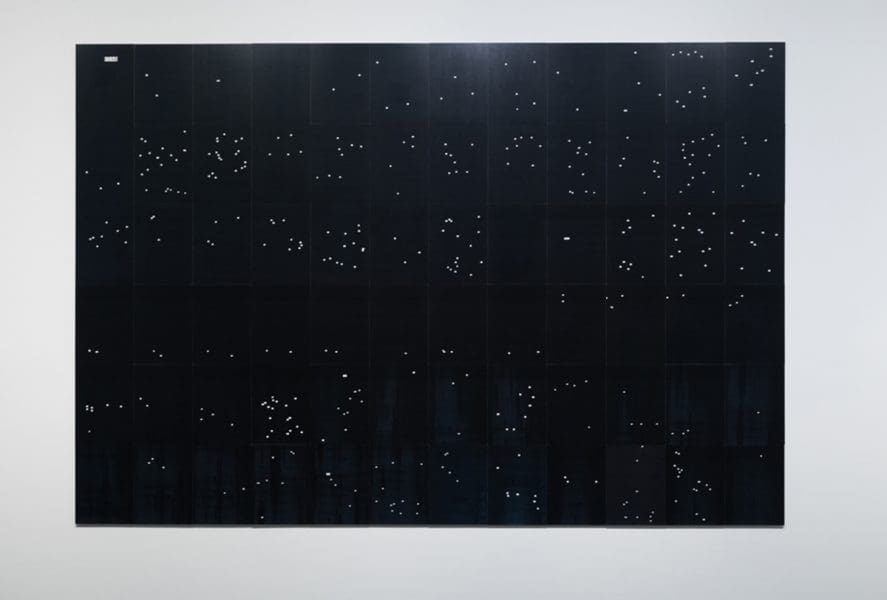

Exploring the use of language as a visual idea, the artist has painstakingly inked over and blacked out every part of every page except the word ‘star’ whenever it occurs. From a distance the drawing appears like a night sky sprinkled with twinkling stars. It’s only when moving up close that the inherent trick of the wordplay becomes visible to the viewer, thereby fulfilling the prophecy of the title.

Two further works of ink on paper are the aptly titled Time Piece and Waiting Game. Time Piece, which looks like a roughly drawn black circle, is a representation of transience and time. The circle was formed with the artist’s pen as it painstakingly moved in sync with the hand of a clock over a 12-hour period. Waiting Game comprises multiple rows of variously sized black ink spots represented as an irregular data-like pattern. Neither as colourful or consistent as Damien Hirst’s dot paintings, nor as random as any of Yayoi Kusama’s dot forays, the circular marks in Waiting Game record the outcome of the artist’s repetitive throws of a 20-sided die over an extended period.

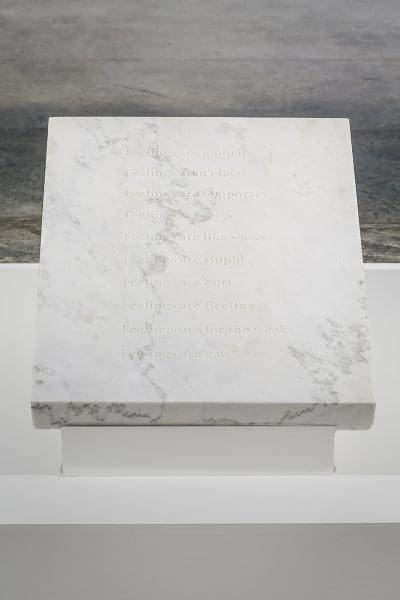

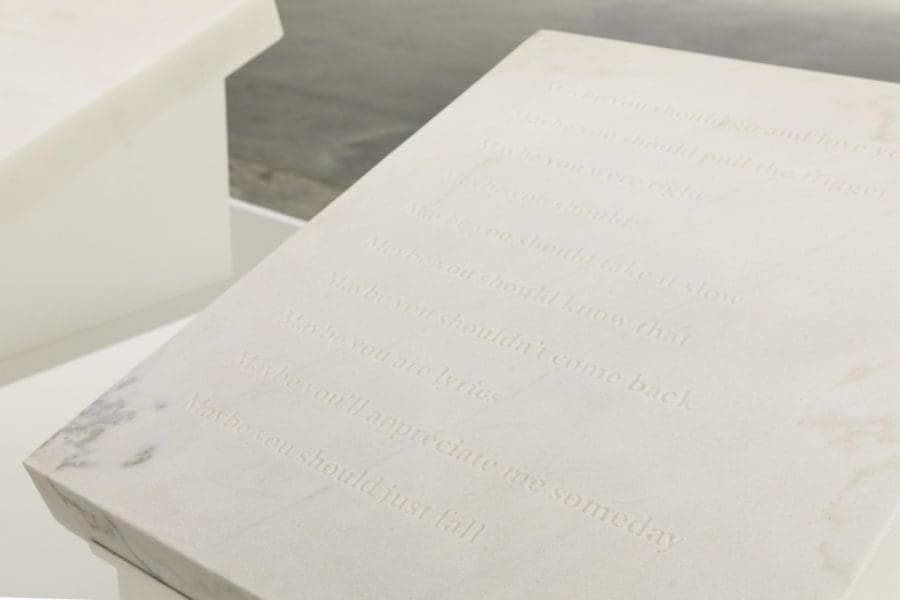

The most successful work in Wong’s display is a series of six contemporary marble sculptures placed on a low horizontal plinth. A clever take on form, Wong fuses the classic appearance of marble with contemporary technology. Each of her white marble sculptures is titled after an internet search engine request. Titled Feelings are, I can’t, Maybe you, People say, Perhaps it’s and She knew: strings of top 10 ‘autocomplete’ searches compiled from global search histories are carved into the tombstone-like sculptures.

The so called anonymity of cyberspace allows us to weave deeply personal questions with a universal desire for human connection; complete strangers accepted. In I can’t, for example, the search suggestions range from the dramatic (‘I can’t breathe’) to the witty (‘I can’t get no satisfaction’) and the pleading (‘I can’t stop loving you’). Meanwhile, the phrase Maybe you delivers a range of wanted and unwanted advice. Reading more like a eulogy, the work She knew includes the lines ‘She knew it all along,’ ‘She knew red was her color,’ and the melancholic, ‘She knew it was destroying her.’ Unsurprisingly, each sculpture also elicits a range of reactions from real-time viewers in the space. Among the laughs, some viewers seemed circumspect or concerned, as if they’d been personally touched by the words.

While Wong’s work demonstrates new possibilities for language, in an era of fake news and reduced privacy, the series also raises the matter of the potential for filtered suggestions to alter what we see and how our personal information is controlled. Despite its understated appearance, Wong’s work reflects Kataoka’s stated aim that the Biennale artworks will be a catalyst to “encourage each of us to consider our own position in society as a starting point.”

Nicole Wong

21st Biennale of Sydney

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

16 March – 11 June