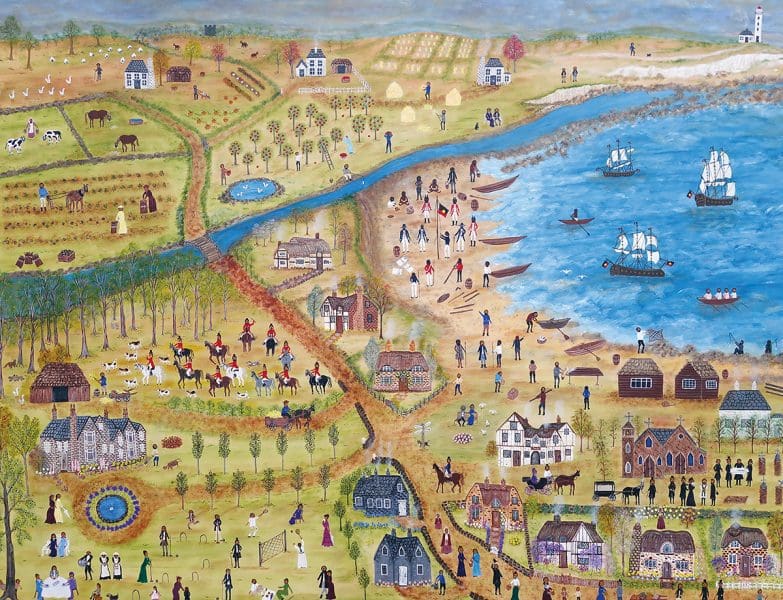

Kait James dishes it out

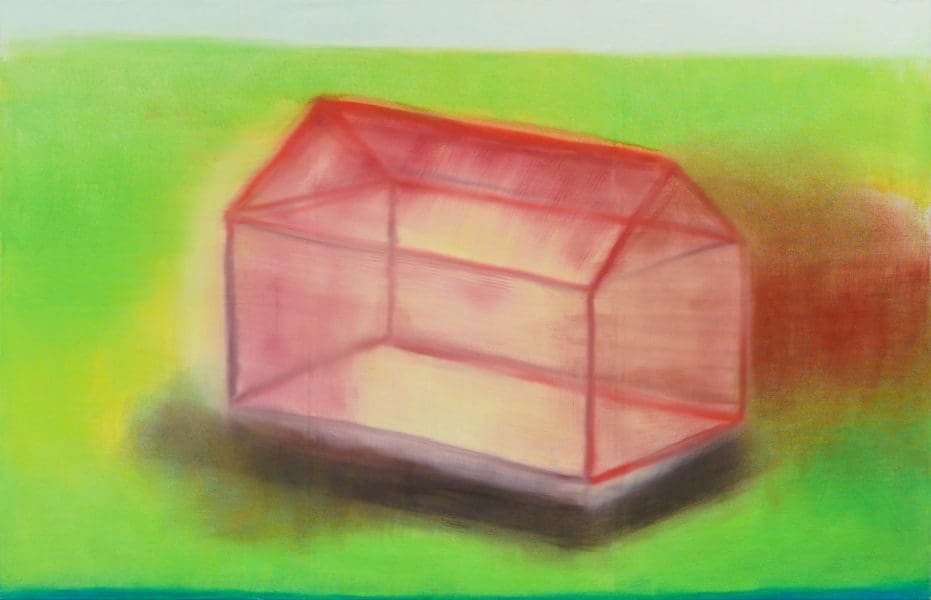

In her major touring solo exhibition Red Flags, currently at Ararat Gallery TAMA, Wadawurrung artist Kait James takes aim at the ongoing commodification of Indigenous culture. She talks to Jane O’Sullivan about kitschy calendar tea towels, souvenir pennants and why she finds it easier to say harsh truths with a little humour.