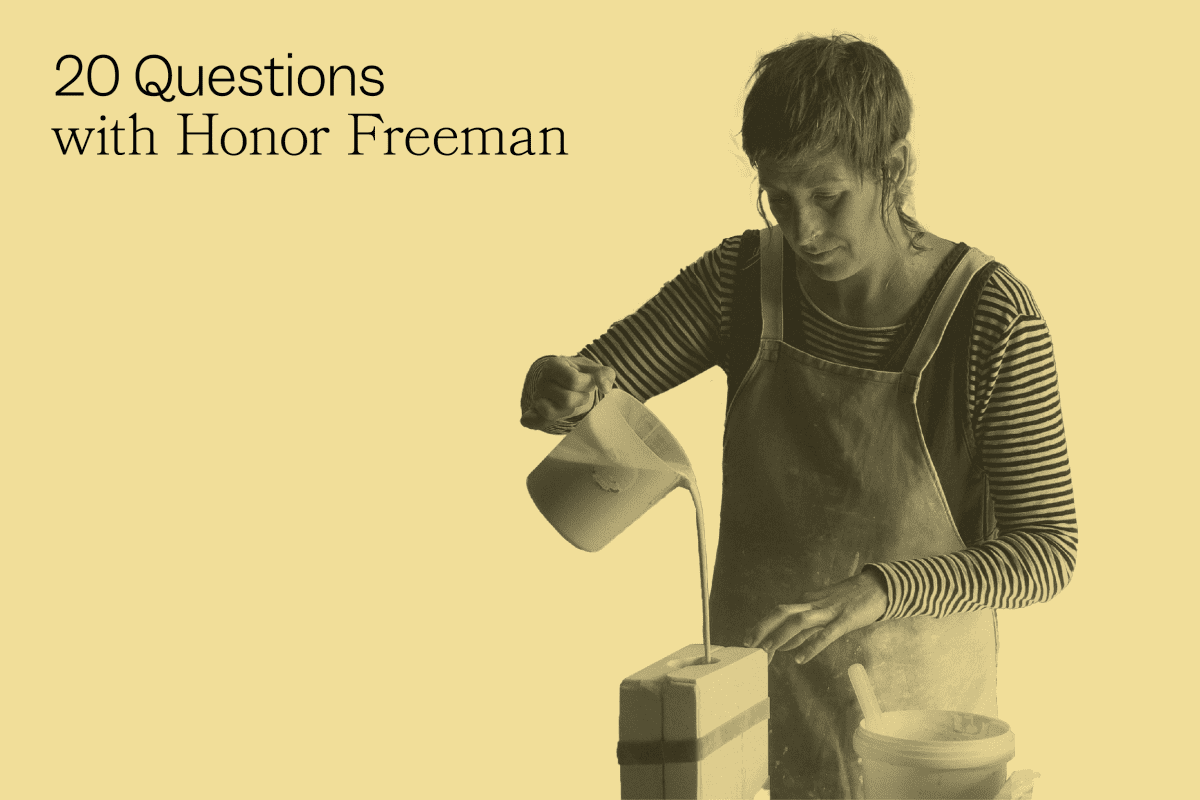

Honor Freeman creates the most exquisite, tactile ceramic objects, often drawing on everyday items from bars of soap to buckets. With a current solo exhibition at Linden New Art, we asked Freeman 20 questions, centering on why she’s compelled to the everyday.

Your first art crush?

Margaret Dodd. In high school when I was first introduced to clay and poring over ceramic journals, I was captivated by her holden car series.

Do you remember the first object you ever made from porcelain?

A small, wonky wheel thrown beaker. It sits on a window ledge in my studio.

Best colour to create with?

Most recently yellow and its many shades (mustard, lemon, chartreuse, citrine, straw, ochre, gold, daffodil, sunshine, canary, saffron, turmeric, honey, sulphur).

Best time of day to create?

Morning.

Order or chaos?

Order.

Solitude or extroversion?

Solitude.

The most interesting thing someone has said to you about your work?

I can’t recall any one thing. Perhaps it’s all the small and personal remembering and memories that people have shared with me over time: stories about grandparents, old shacks, the nostalgic smells the work evokes, transporting people to another time.

You say that you’re compelled to the “mimetic qualities inherent in clay”. Can you unpack that a little more?

Clay has a curious and compelling ability to almost perfectly mimic other materials, surfaces and textures—a shape shifter of sorts. Working primarily in porcelain with the process of slip casting—traditionally an industrial process used for creating multiples—slip casting involves the creation of plaster moulds of originals (used soap, towels, buckets). Liquid clay slip is poured into the cavity of the moulds and left to rest. Plaster is a naturally thirsty material and drinks away the moisture from the liquid clay creating a porcelain skin within the mould cavity. The casts are a memory of the past form, like a tangible whisper or echo of that object, eternally preserved and remembered but subtly changed.

You’ve also talked about being captivated by the ‘everydayness’ of objects, creating things like ceramic soap, bread tags and door handles. What’s so captivating about the ordinariness of things?

I’m drawn to the unassuming ordinariness of the everyday, and thinking of what lurks just beneath the surface. There’s all sorts of secrets, as though objects bear witness and hold untold stories, or are mnemonic devices prompting memories and remembering. They can reveal and tell us much about who we are. The everyday is a rich source material. I like that there is an embedded and unspoken language within the objects that say so much without needing words, an existing poetry.

These banal and humble objects have a democracy to them and are often full of humour and are metaphors for life. There can be layers, but they are also just simply what they are, and people understand them. It’s a gentle way into the work for the viewer; a bucket or a bar of soap are something we all understand, we know how they feel in our hands, the weight of them, what they do, we have a relationship with them.

Do you think the quietly domestic has been overlooked in contemporary art, at least historically?

Artists are often drawing upon what is at hand, and the everyday has more broadly been evident and reflected within a great number of artists’ work and practices. The quietly domestic, however, perhaps having largely and more traditionally been the realm of women, I do think has been overlooked. Thankfully, there has been a shift and rebalancing in recent time, with a focus on more diverse voices across not just visual art, but film, TV, media, literature. It’s an exciting time to see our diverse communities reflected in these spaces.

Why do you think people are so drawn to tactile art?

It’s a very digital and screen-based world most of us live in, and while this connects us in many ways, it also robs us of time and grossly disconnects us from the haptic and tactile world. I think the tactile has always had an orbital pull, but more so recently with people feeling a need for it, for balance. Whether that be physically engaging with a process and taking up ceramics classes, or viewing tactile, time-embedded works in the hope of somehow absorbing a sense of (precious) time.

Most memorable art experience?

Probably the non-curated private viewing I was afforded in the bowels of the Art Gallery of South Australia during The Collections Project residency. The quiet intimacy of being up close with and carefully handling objects from across cultures and centuries was a deeply moving and profound experience. Thinking about the way objects hold their own stories—the evidence of the unknown makers hands, the stories of those who made and used them—they seemed almost to vibrate at times.

Memory is very important in your work. How do you see that relationship between memory and art making?

Clay, particularly porcelain, is a material with memory, remembering the hands of the maker, the subtle marks of finger prints evidenced on the surface of pieces. Porcelain, because of its high plasticity, has a curious ability to warp during the various stages of making and firing, recalling a knock. Or where one side receives more of a draft or concentrated shaft of light, drying unevenly. You might think you have righted the flaw, only to have it reemerge in the final firing. It remembers. I both like and loathe this material quality, the poetry of it.

If you could collaborate with any artist, dead or alive, who would it be?

Clare Twomey.

For your 2019 show Ghost Objects at the Art Gallery of South Australia, you looked at the relationship between objects, grief and mourning. Reflecting a few years later, what did you discover in those connections?

At the beginning of the project I was drawn to the small things, like Victorian mourning jewellery, which are embedded with powerful emotions of loss and love. A keystone object for me was a tiny Roman glass flask, called a lachrymatory. For a long time, it was thought these vessels, found in great number in Roman, Greek and Hebrew tombs, were used to collect and store the tears of mourners.

This story has in more recent times been debunked by science, but it led me to think about tears, and my own experiences of loss and sadness: the importance and power of these objects and rituals to offer solace in times of grief and mourning, helping to make sense of the loss. Sadly in our western culture, our rituals around death and mourning are practiced with an antiseptic restraint.

You live in a coastal town in South Australia. What are the vices and virtues of living semi-regionally as an artist?

My family and I have recently fulfilled a long-held dream to flee the city and pursue a life by the coast. We wanted to be nearer to nature, building the pursuit of wonder into our family’s daily life. The Fleurieu Peninsula, Ngarrindjeri land, is where I now live and work. Most mornings, regardless of the weather, I swim with a small group of friends across Horsehoe Bay. I relish it. No two swims are ever the same. To experience the wonder. To feel small and exhilarated.

Are you a good cook? Any signature dishes?

I’m okay. There’s always room for improvement according to the small folk in my family! I’m known to bake a biscuit or two with a strong focus on tahini. When my dad was alive, he would deliver lamb shanks (“fallen off the back of a truck”, his words), and I would cook a lamb shank curry with a lemon rice pulao.

Classic ‘Honor Freeman’ drink order at the bar?

G & T.

What will we see at your current show at Linden New Art?

A suite of ceramic works exploring the metaphoric qualities of water: porcelain puddles, a pile of plugs, hot water bottle, a pile of used soap. There is a bathtub raised up on hand built Besser blocks, as though a stranded vessel or boat escaping a flood. There’s also contemporary lachrymal vessels used to collect tears, a porcelain pillow, rain gauges and buckets with a mother-of-pearl glaze. The ceramic works are exploring the idea of rising tides and flooding, as representative of our own internal struggles.

Is there an object you’d love to create in ceramic form but haven’t? Think as impossibly as you’d like!

A life-size raw clay dinghy pushed out to sea to slowly dissolve.

Ebb

Honor Freeman

Linden New Art

Until 4 September