Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

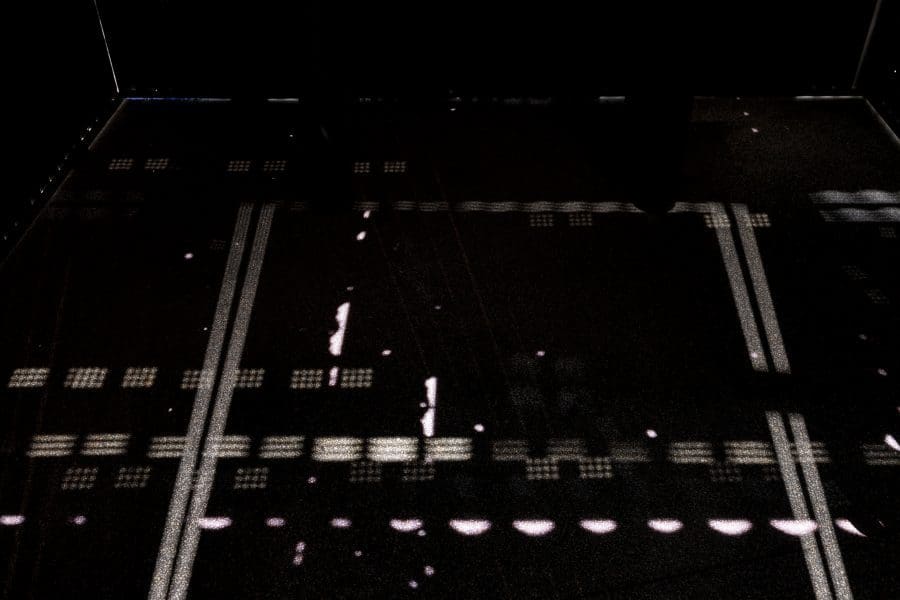

Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park 2021, installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park 2021, installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

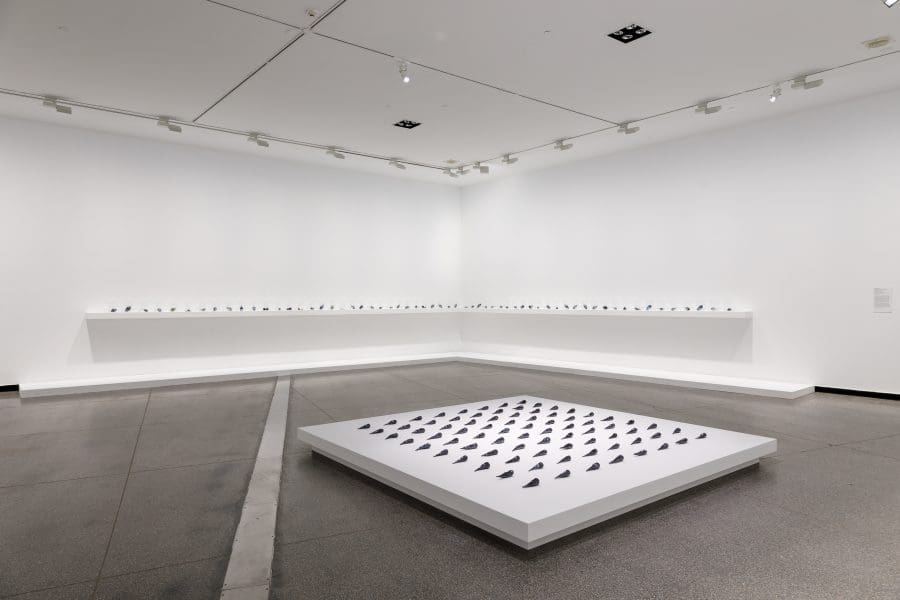

Yhonnie Scarce, Blood on the wattle (Elliston, South Australia, 1849) 2013, installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased with funds donated by Kerry Gardner, Andrew Myer and The Myer Foundation, 2013. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

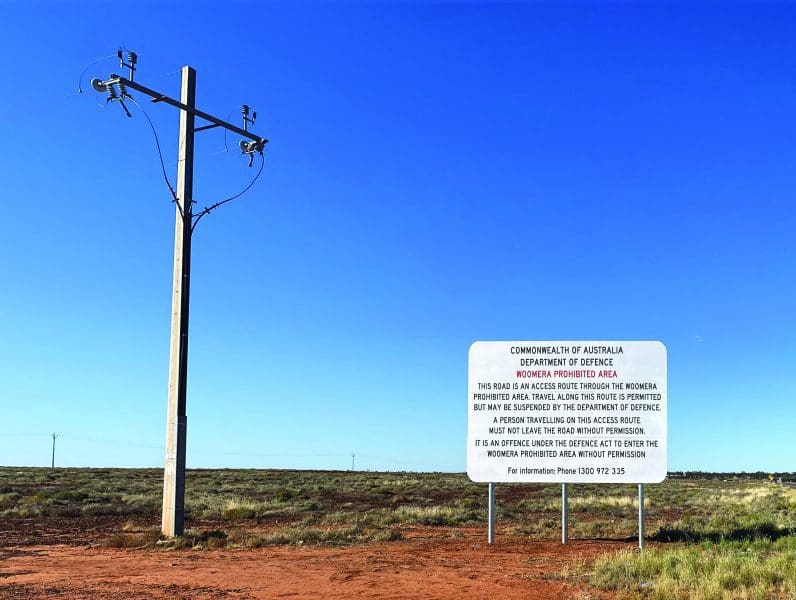

Yhonnie Scarce, Prohibited Zone, Woomera, 2021, research photograph. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne.

Installation view, Yhonnie Scarce: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

Yhonnie Scarce, Blood on the wattle (Elliston, South Australia, 1849) 2013, installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased with funds donated by Kerry Gardner, Andrew Myer and The Myer Foundation, 2013. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

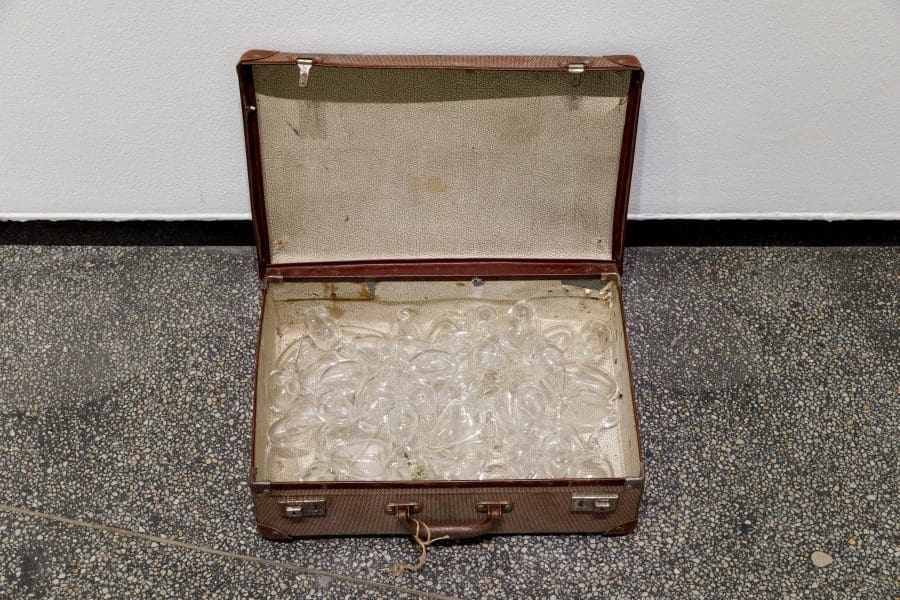

Yhonnie Scarce, The day we went away 2004 installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Private collection, New Zealand. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

Yhonnie Scarce is a Kokatha and Nukunu artist working with the delicate yet surprisingly robust material of glass. Taking on the shapes of bush plums and yams, Scarce’s glass forms are often used to build immense installations referencing contemporary and historical Aboriginal experience. Colonisation, nuclear testing in Australia and family heritage are all consistent themes throughout her practice. Increasingly working with architectural space, Scarce also looks at how built structures can be receptacles for memory, bearing witness to all that has occurred around and within them. Following on from In Absence (the National Gallery of Victoria architecture commission she completed with Edition Office in 2019) Scarce has now created Missile Park, the title piece of a touring survey exhibition. Scarce spoke to Briony Downes about the power of visual narratives and how her work reveals hidden truths.

Briony Downes: Missile Park was commissioned by The Australian Centre for Contemporary Art and consists of a series of sheds recreated for the gallery space. Can you tell me about these and what they represent?

Yhonnie Scarce: Missile Park references nuclear tests undertaken in South Australia, the cover-ups involving the deaths of Aboriginal people during that time and how the Australian and British military were complicit. I have recreated three sheds recalling similar structures I have seen at Missile Park in Woomera, which is the town where I was born. It’s still an active military base.

In the ACCA commission, the sheds are like tombs. They are made from found galvanized zinc, bitumen paint and shellac and inside the sheds are collections of glass bush plums. There is one shed you can enter and be close to the plums. You go in, close the door and wait for your eyes to adjust to the darkness. Then you see these plums sitting on metal tables as though they are altars. The plums represent us as Aboriginal people and our patience.

I know a lot of Aboriginal people have the same view – we do fight for truth telling but we are also very patient with it. It’s a way of holding onto our stories and knowing the old people will eventually help us uncover it. The truth will come forward.

BD: What is it about architectural space that draws you to it?

YS: I’ve been interested in buildings and architecture regardless of whether they are occupied or not. They are knowledge holders. I strongly believe that in areas where trauma has occurred (genocide, massacres), the built structures hold memory of those events. In Absence was about that. When people engage in conversation inside In Absence – it’s like the structure is listening. It’s the same with Missile Park in Woomera – there are these sheds, these structures out in SA that know exactly what has happened. They are like witnesses.

BD: Radio National presenter Daniel Browning recently described your glass recreations of native foods as anthropomorphic. Can you tell me about the foods you choose to recreate and the meaning behind how you assemble them?

YS: I use them to represent Aboriginal people. With the bananas and the bush plums, these represent our culture and the food we eat, while the glass yams in Burial Ground, 2009, and Blood on the wattle (Elliston, South Australia,1849), 2013, represent the deceased. More recently the plums have come to represent children and the different stages of pregnancy.

I am very close to my work. I love who I am, I love where I come from and I’m very proud of my heritage. When I make the food it’s very much about the love I have for my people.

The large bush plums inside the sheds of Missile Park are all black and like time bombs. In nature, bush plums are really tiny, so these bigger ones are like soldiers to me, sitting very patiently inside those sheds. That’s how and why I make these forms, they are not just food, there’s something else going on for me. I love that I can make them in large numbers, sometimes into the thousands. They create their own landscape. It’s that representation of country as well. It’s a multi-layered way of storytelling through glass.

BD: There are 10 other pieces in the exhibition and some are photographs with a connection to your family history. Who are the people in these images?

YS: Dinah, 2016, is my great great grandmother. Accompanying her image are some glass bush plums on a shelf to honour her as the great matriarch of my family. She is the grandmother of my grandfather Barwell Coleman, who is in Working Class Man, 2017 – an older photograph I’ve enlarged. The photograph was originally taken at Andamooka Opal Fields where my grandparents lived for a number of years and Barwell worked as an opal miner. With this photo is a bucket of glass yams to symbolise how hard he worked. The foods here are like gifts to my family.

Then there’s Florey and Fanny, 2012, which is about my grandmother and her grandmother, and relates to domestic servitude and the strength of the Aboriginal women in my family. The photos in Missile Park are from my family history archives. Family photos turn up in my work quite a lot, but these are more of one person than all the family together.

BD: Recently you undertook a research trip to six countries to visit memorials, nuclear disaster sites and locations where trauma had taken place. In the months since, how has this experience affected how you think about how we memorialise history, and the lack of similar kinds of sites in Australia?

YS: Research has been a large part of my practice for the last 15 years. It’s just lately it has become more specific. I’ve been looking more closely at memorials and monuments with a colleague, Lisa Radford. We travelled together to look at monuments in Europe – locations of the holocaust and nuclear disaster sites like Chernobyl. It’s comparing notes with what is not happening here. The nuclear tests in Maralinga, SA, and the Montebello Islands, WA, are still shrouded in secrecy.

The lack of respect and recognition of the Aboriginal people that died fighting for country in the Frontier Wars and the massacres that happened during that time – or even after that – there’s very little evidence of the government talking about it, or even recognising it happened.

It’s been amazing to see how other countries have referenced past trauma by recognising it – that way you can talk about it, deal with it and move forward. There’s a lot happening in the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal community to recognise history, but it needs to come from a federal level for us to have sites remembering our ancestors. That’s a way of healing, and not just for us as people but for healing as a country.

Missile Park

Institute of Modern Art

17 July – 18 September

In the dead house

Yhonnie Scarce

THIS IS NO FANTASY

4 – 30 May