Shari O’Dwyer Dances with History

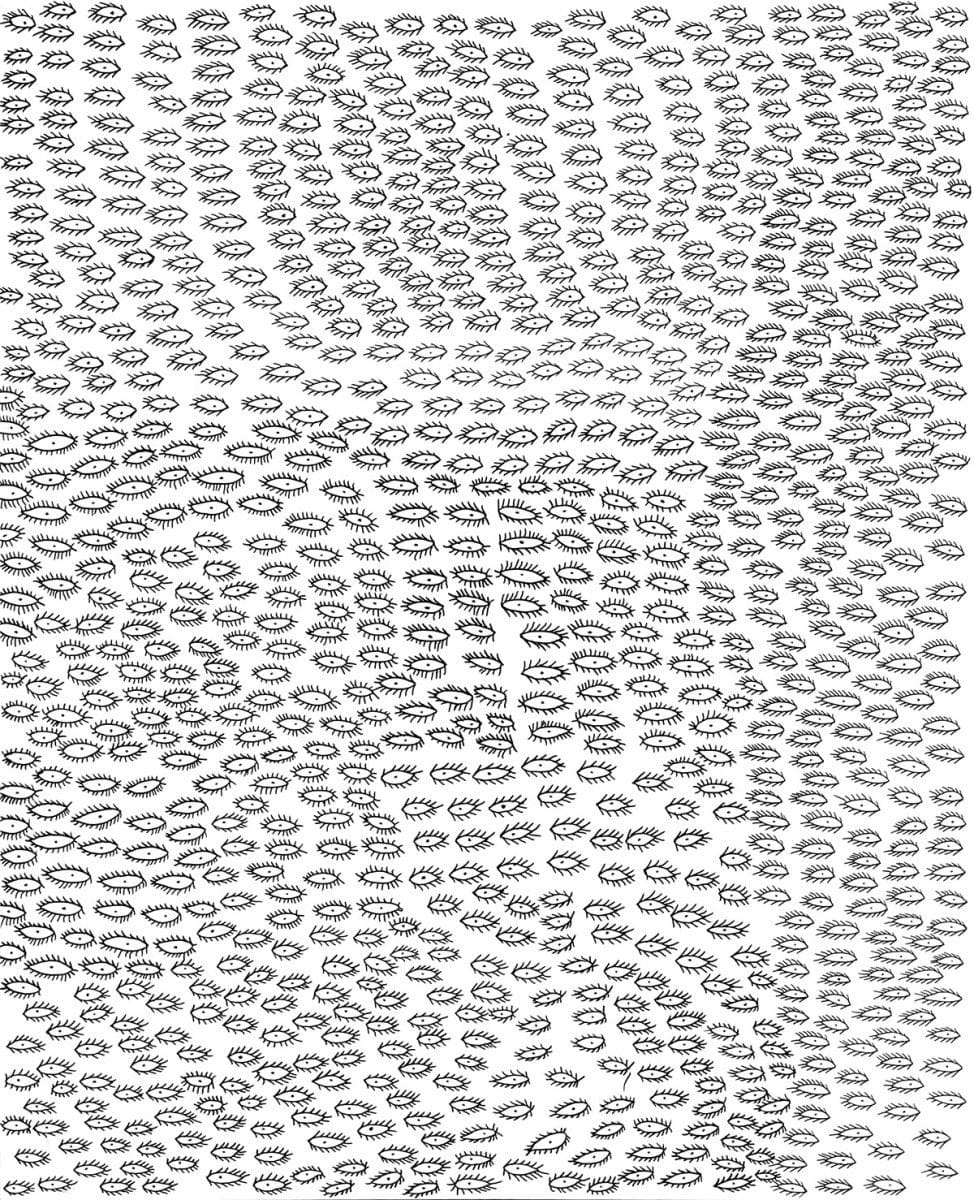

holemtaet hemia (hold this/ hold this tightly) is a new solo exhibition from Shari O’Dwyer at The Condensery, Toogoolawah, Queensland, that explores the woven memories between generations of South Sea Islanders in the Australian colony.