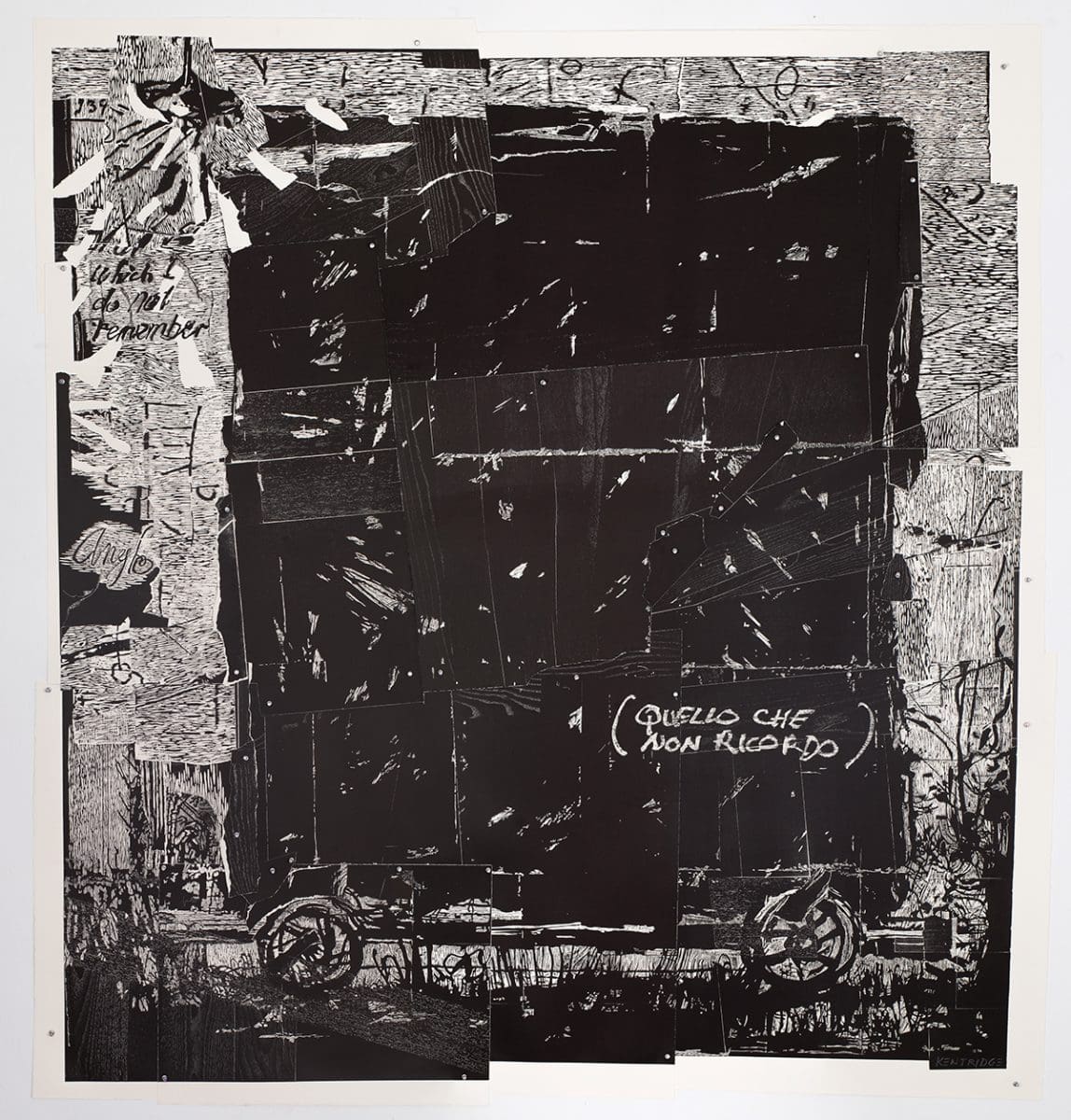

Can you have too much of a good thing? William Kentridge seems determined to find out in his survey show, William Kentridge: that which we do not remember, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Apparently this is the artist’s first foray into curating and he describes his strategy as “a deliberate over loading.” And the exhibition is indeed full to bursting with many, many very good things.

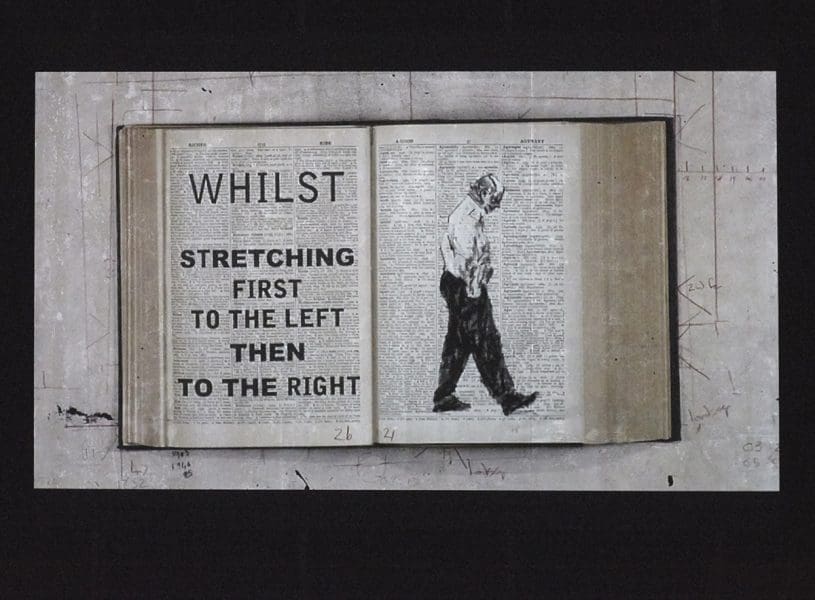

Spanning some 20 years of artistic output, William Kentridge: that which we do not remember features the rubbed-out and re-worked animated drawings the South African artist is so well known for, as well as multiple still drawings (some life-sized), lots of prints, a few sculptures, several multi-screen video installations, an entire reading room filled with books on his practice and even a tapestry. As Kentridge puts it, the show is “very much about the excess of the studio.”

But thankfully, Kentridge delivers quality as well as quantity. Poke a pin in William Kentridge: that which we do not remember and you will hit something amazing. The consistency of the artist’s vision over two decades, and his ability to move seamlessly between mediums, is in itself one of the highlights of the exhibition.

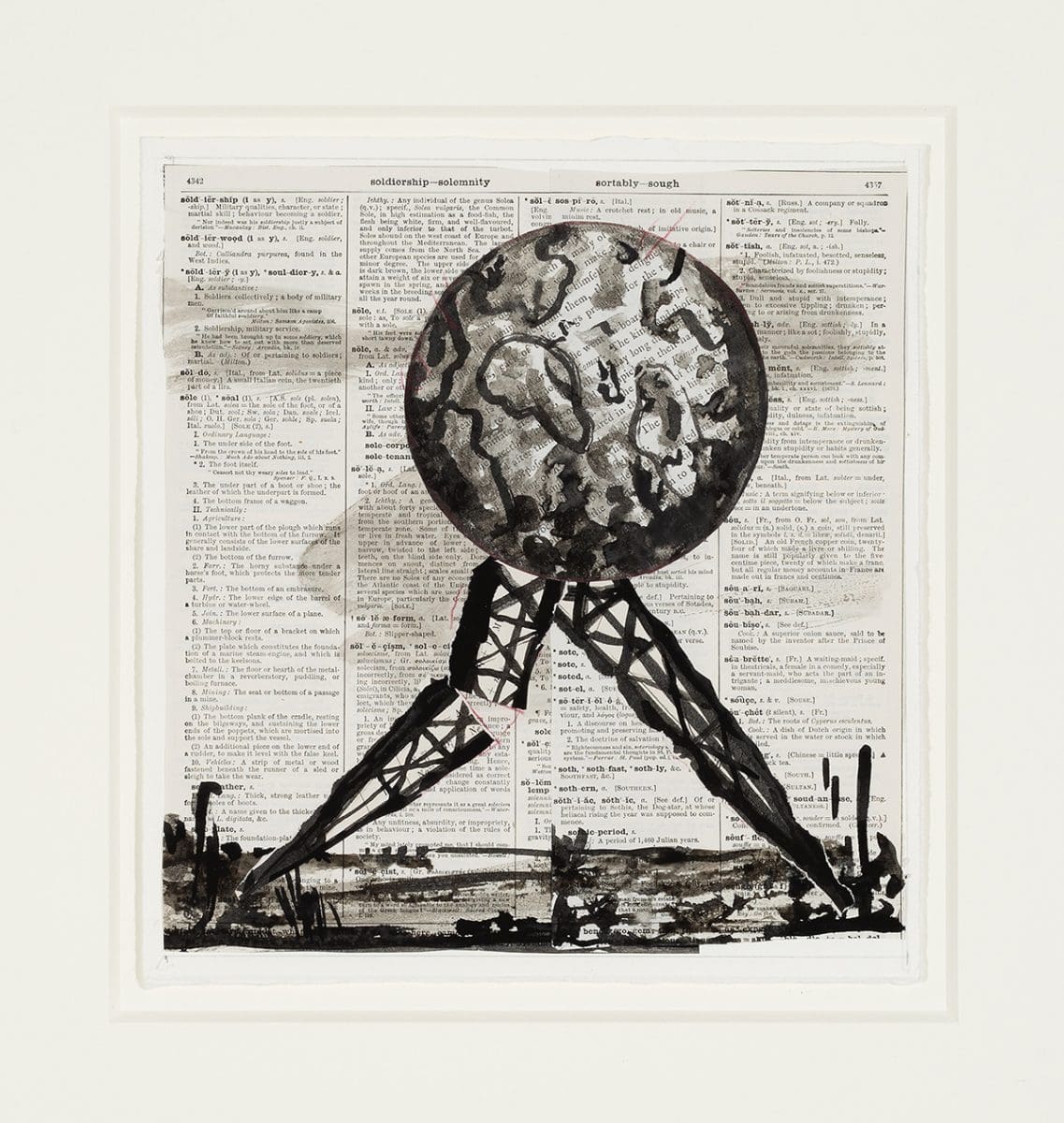

But for me, the real highlight was the room which featured three of Kentridge’s films from 2003: 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, Day for Night, and Journey to the Moon. These three videos are projected across nine screens simultaneously and it didn’t even occur to me to try to figure out which screen belonged to which. Together they form a remarkable meditation on the comedy and hubris of human ambition and they pay tribute to the magic of creativity.

On many of the nine screens we see Kentridge in the studio and at first it seems as if he is going to reveal the secrets of his working methods. But instead he delights us with cinematic sleight of hand. A cup of coffee poured over a sheet of paper resolves into a self-portrait, he then wipes out the whole drawing by simply running his hand over it. Elsewhere he draws himself full scale. A coffee pot shoots into space like a rocket, ants race across the screen tracing patterns like restless constellations. Books, chairs and drawings defy gravity and fly around the room only to be caught by the artist. Kentridge casts himself as the man in the moon and recreates the famous shot from the iconic 1902 film by Georges Méliès, but instead of getting hit by a rocket, he gets his coffee pot in the eye. A naked woman shows up and gives him a cuddle. More than a sum of its parts, the overall effect is absurd, wonderful and, somehow, deeply optimistic.

As the artist intended, William Kentridge: that which we do not remember is an exercise in information overload. In fact, you could spend a 9-to-5 week in the vast darkened spaces Kentridge has filled and still come back for more. The show, like the works themselves, is a palimpsest; densely layered and almost impossible to grasp on one viewing. Kentridge is a gifted storyteller, and, like a good book, this exhibition will reward those with time to read it again.

And, if after multiple visits, you still find that too much Kentridge is barely enough, more can be found in Right Into Her Arms at Annandale Galleries until 8 December, as well as in the opera Wozzek at the Sydney Opera House in January and February 2019.

William Kentridge: that which we do not remember

Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW)

8 September – 3 February 2019

Right Into Her Arms

William Kentridge

Annandale Galleries

6 October – 8 December