Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

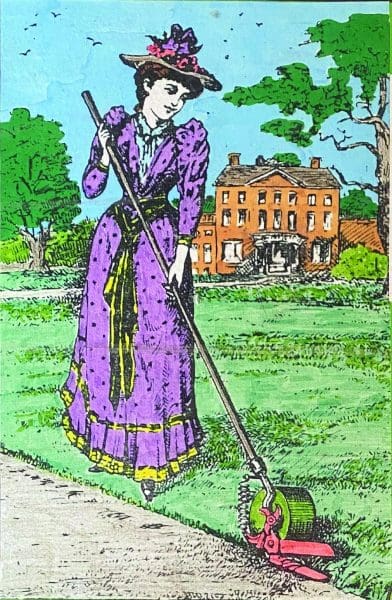

Grant Simpson, hand-coloured photocopied print, from 1895 advertisement for Adie’s Lawn Edger.

In Georgian England, everyone coveted lawn. It was cool, calming, tidy, and ensured a pleasant and private space for ladies in Empire-waist dresses to take a turn together. Because it required constant maintenance, lawn was also a status symbol: “At that time, all you could cut grass with was a scythe—or you could graze sheep,” laughs Richard Heathcote, curator of The Blade, an exhibition tracking the story of lawn in Australia. The thing that “democratised lawn,” he says, was the 1830 invention of the rotary mower.

While this love of English lawn travelled to Australia with colonisation, Indigenous peoples were already expert in care and maintenance of native grasslands. “Fire-sticks were an important tool in Australian management of grass,” says Heathcote. But lawn is vastly different from grazing meadows, and the trend towards turf was firmly planted by the time smooth green grass was rolled out at Government Houses across the states—what Heathcote calls “power lawns”. This vista continues to be de rigeur; Parliament House is famously built into a lawn-covered hillside.

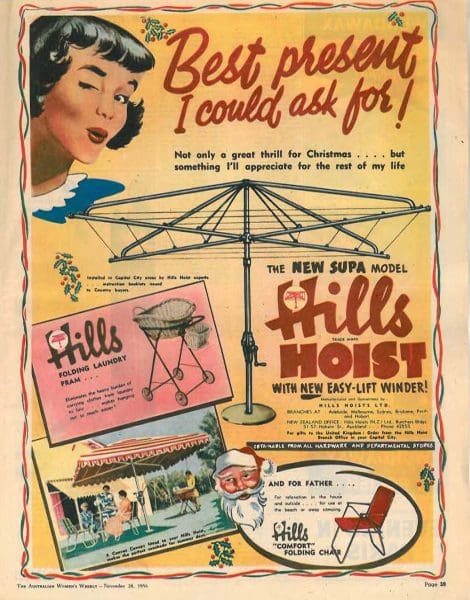

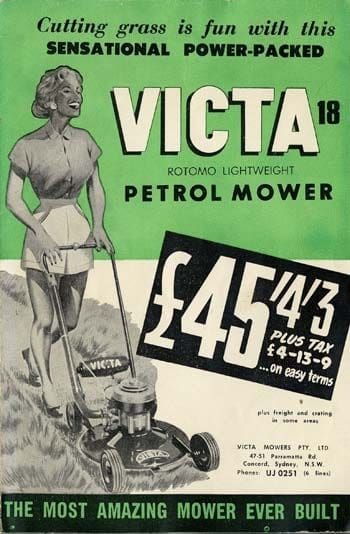

Through artworks, historical artefacts, and vintage lawn-care advertisements, The Blade explores the Australian history of lawn from kangaroo grass to the footy field; the scythe to the electric mower; the suburban Hills Hoist to the sweeping verdure of state buildings. It features a notable collection of intriguing contraptions for lawn maintenance—such as a giant corkscrew-like device specifically for the removal of dandelions—and, as a touring exhibition, each iteration will include new elements specific to the location. This is a fascinating story of changing attitudes to technology, the environment, and public and private space—through the plant most grown in our gardens.

The Blade: Australia’s love affair with lawn

Canberra Museum and Gallery

21 November 2020—20 February

This article was originally published in the January/February 2021 issue of Art Guide Australia.