Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

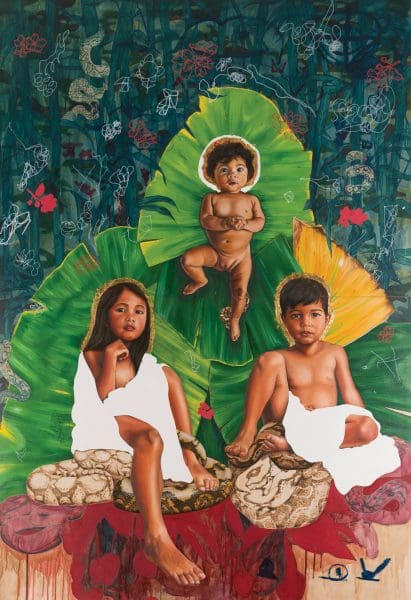

Marikit Santiago, Original Sin (detail) (2018), acrylic, oil, pyrography, pen, 9ct gold leaf, pen and paint markings by Maella Pearl, aged 4; and Santiago Pearl, aged 2; on found cardboard, 148 x 218 cm. Photograph: Zan Wimberley. Image courtesy of Firstdraft.

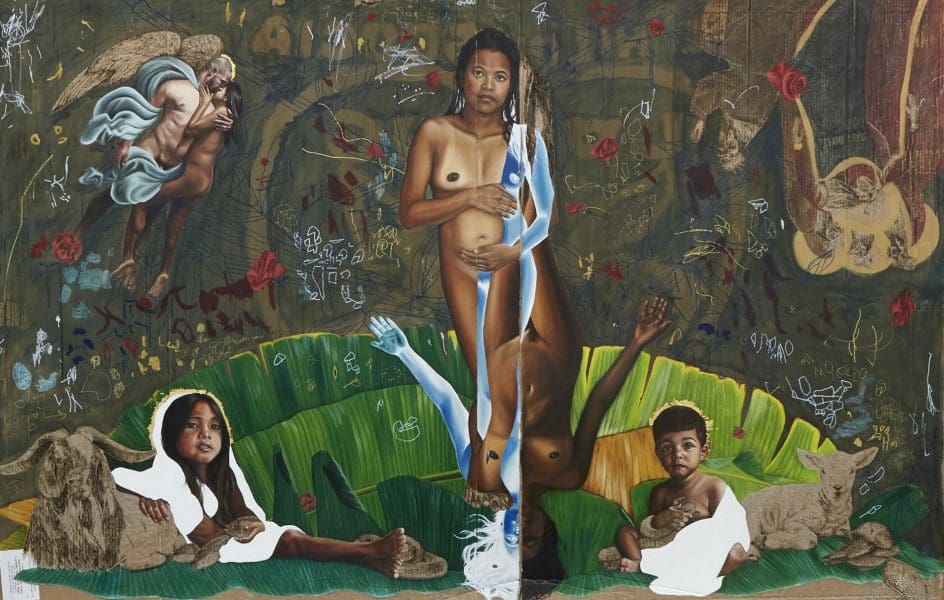

Marikit Santiago, Original Sin (2018), acrylic, oil, pyrography, pen, 9ct gold leaf, pen and paint markings by Maella Pearl, aged 4; and Santiago Pearl, aged 2; on found cardboard, 148 x 218 cm. Photograph: Zan Wimberley. Image courtesy of Firstdraft.

Drawn and Halved, durational performance collaboration, Casey Jenkins (Sh) and Ottilie Sh, LAPSody, Theatre Academy – University of the Arts Helsinki, Finland 2019. Photograph: Julius Töyrylä.

The Artist Is Distracted, interactive performance and selves portrait, Casey Jenkins (Sh) and Ottilie Sh, Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne 2019. Photograph: Emma Byrnes.

Maella Pearl, Santiago Pearl, and Sarita Pearl at Yavuz Gallery, 2020. Photograph: Marikit Santiago.

Lucreccia Quintanilla, A Steady Backbeat, 2017, ceramic, sound work, sand, broken telephone used as a sound playing device.

“I had a choice of either removing myself from my art practice for a period of time—so, not creating work— or creating work which we were both involved in,” says Melbourne artist Casey Jenkins about negotiating life as a new parent.

Jenkins’ practice deals with feminism, autonomy and power. It would not have felt honest to set those interests aside, and so the task became how to make work with their child.

Jenkins is not alone. Some of the challenges that face artists who are carers are common to all parents, but others are unique to creative practice. Famously, the English author Cyril Connolly pitched it as a battle when he said in 1938 that “there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall”.

The first work that Jenkins made with their child Ottilie was a performance called Drawn and Halved, which was staged as part of the Lapsody Festival in Helsinki in 2019. “I drew a line down my middle and, over the course of the work, I tried to create an art vessel out of clay with one hand and care for Ottilie with the other side of my body. That had been how I thought of it,” explains Jenkins. “That you’re split. You have to divide your attention and both will suffer—your art will suffer and your child will suffer. But through doing that work I realised my child made that work.”

The artist also makes an important distinction: “They didn’t detract from my work or my self-expression. They had changed who I was and what I was expressing.”

Connolly’s bleak description doesn’t leave much room for these sorts of self-realisations. It’s also damaging for artists who might feel like they’ve ‘lost’ when dealing with exhaustion, lack of support, or other health or care needs. (Not all phases of creative practice are about output, after all.) The phrase “good art” also contains more than a few assumptions about who and what art is for.

Over the years, Jenkins’ practice has ranged from solo durational performances to craftivism and communal and participatory works. They have often thought about issues of timing and access. “If you’re displaying a supposedly feminist work which is going to be launched at bath-time, then I don’t think that’s really feminist,” Jenkins says. Their second project with Ottilie, The Artist Is Distracted, 2019, extended these ideas. Ottilie was 17 months old by this time. Rather than trying to “make my child fit in with the art world, I wanted that art world to have to come to us,” Jenkins says.

The sessions were held after nap-time. Audience members who wanted to participate were given a distraction device, basically a restaurant buzzer, and Jenkins would use it to call them over if and when Ottilie was ready. Then they would all work through an activity from the Marina Abramović Institute, such as counting grains of rice or drinking a glass of water slowly—but instead of following Abramović’s instructions, participants were asked to emulate Ottilie. If Ottilie chucked rice in the air, so would they. It was “gentle chaos,” says Jenkins, but there were also “really beautiful moments of connection”. Ottilie enjoyed the engagement at their level and Jenkins, rather than feeling torn, felt whole.

A year later, Jenkins is back to making solo work again, but is also working on a (Covid-delayed) street art workshop for kids, in a challenge to the absence of women and families from the street art world. Jenkins also sees the workshop as a way to “produce art and interact and play with my kid” but working with children is important to them on many levels. “Kids are human beings and deserve to be engaged in society,” Jenkins says simply.

Marikit Santiago’s work has also been forged by—and with—her kids. “I fell pregnant with my first child while I was studying my MFA,” she says. “I was terrified that I wasn’t going to be able to make it work.” She came back, however, then took another break for her second child, and had her third the year she graduated.

Santiago was determined. “If I’m making the effort to find care for my children and making the commute, I need to make it worth my time,” she says. She now works out of a studio in the garage of her home in Western Sydney. “Once I go into the studio, it’s on,” she laughs.

Just a few months ago, Santiago’s painting of her three children, The divine, 2020, won the prestigious Sulman Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Giant palm leaves, yellowing in places, set off the golden halos behind their heads. The two oldest are wrapped in white cloth, neatly blending religious and art historical references with bath-time.

Alongside being portrait subjects, her kids also contributed to the work, and their pen and paint marks cover the dark jungle background. Santiago has been developing this method of collaboration for some time. “I found that the artworks that I was influenced by had a really good combination of typical realism alongside, or right next to, more gestural mark-making,” she says. “I was like, how can I do that? In my early years, I was quite rigid with my technical skills, and then I thought, you know, if I can’t do it, then I’ll just get someone who can.”

They are young children and Santiago gives them guidance, but the marks are theirs. “I think I know them enough,” she says, about whether she worries about accidents.

While the decision to involve them is largely about visual interest and the contrast between their loose gestural marks and her refined technical skill, the juxtaposition also seems a natural fit in a practice concerned with conflicts of identity and cultural inheritance. “Nothing’s more complex to me then navigating my own identity,” she says, describing herself as a second-generation Filipino migrant with Australian nationality, who has lived in Australia almost all her life. That interest has only intensified since she had kids.

Santiago is now working towards her first solo institutional exhibition next year, but is already thinking further ahead. “I wonder how long they’ll keep working with me. I mean, their marks are inevitably going to change,” she says. “Perhaps it will become much more of a true collaboration, where we work together and respond to each other?”

For Melbourne-based multidisciplinary artist Lucreccia Quintanilla, having a child also left her thinking about cultural inheritances.

She was early in her practice and remembers feeling disillusioned with the art scene, but it wasn’t until she had her son that she realised just how far that went.

“I started to think about what it meant to pass something down to someone and what I was passing down,” she says. She had come to Australia from El Salvador as a teenager, but “had not really assimilated to Australian mainstream culture. I needed an outlet—and that’s my whole practice now, the whole of it,” she says.

Her son is 14 now, and motherhood has played a big part in her shift away from an object-based practice to making sound work. “Having a child gave me the confidence,” she says. “I knew that I was wanting to do things differently—sometimes you just think, I have a gut feeling about how to do this thing right now.”

A few years ago, when her son was 10 and that shift in her practice was developing, she took him with her on a one-month residency to Banff, Canada, to work on a ceramics project. It was a rare opportunity. There are relatively few family-compatible residencies. This one, like most, did not include childcare. It involved a lot of negotiation (especially when her son claimed the other resident artists as his friends, not hers). But it also showed Quintanilla how her work was part of his life, and how connected he felt to it at that time.

“He felt so part of the process,” she says. “And since I’m thinking about these things, I wonder what he has to bring to it, so I asked him if he wanted to do something.”

Back in Melbourne, the work they made together dealt with language, culture and heritage. It was a recording of their attempts to learn Lenca, an Indigenous Salvadoran language. They occasionally talked in English too, but not Quintanilla’s Spanish. “When I listen to it, I hear us bouncing back and forth,” she says. “It’s a complex conversation.”

It helped that, by this time, she had found her way into a strong, open community in Melbourne and knew she could exhibit what she calls “a family thing”. The work was shown in an exhibition called Family Grimoires: The Diaspora Fantastic at Seventh Gallery, and a later reconfiguration was also included in m_othering the perceptual ars poetica at Counihan Gallery. Quintanilla says that these days, she is very confident asking for what she needs as a parent in the art world.

“I’ve made a choice to be an artist,” she says. “Because of it, I want to create the conditions for myself and my child. I have nothing to lose.”

“I have found people are very supportive and really listened to me. When I was working in the corporate world, I had to breastfeed in the toilet.”

Her community is very different to the art world that she first encountered. “We have this care thing. We will do things for each other,” she says. “People are making worlds out there, you know.”

As DIY projects go, it’s a complicated one. There are issues around carer-friendly event scheduling, exhibition projects and residency opportunities. There are also, in the wider art market, unspoken value judgements about what a serious artist looks like. (And as always, proving ‘commitment’ is easier for some than others.) And then there are also the broader cultural judgements about parenthood, particularly the role of mothers in overseeing the visibility and protection of children in an online world.

The ideal today, says Jenkins, is “mothering behind closed doors, keeping it all quiet and safe” which can mean that mothers in the public eye are quickly branded “attention seeking” or exploitative. Jenkins is wary and thoughtful. “I respect anyone’s choice to either present their child or not present their child in public,” the artist says. “For my child, at this point in time, I don’t want to model fear of the world.”

Santiago is also pragmatic about being visible in public life as a mother. “I want to make work that’s authentic to me, even if that means painting subjects that have maybe been taboo, or people don’t want to see in the art world,” says Santiago. “I’m most confident in expressing art that is personal to me. And that’s what’s happening to me right now—I’m a mother.”

IMMACULATE

Casey Jenkins Online

Monthly performance

This article was originally published in the January/February 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.