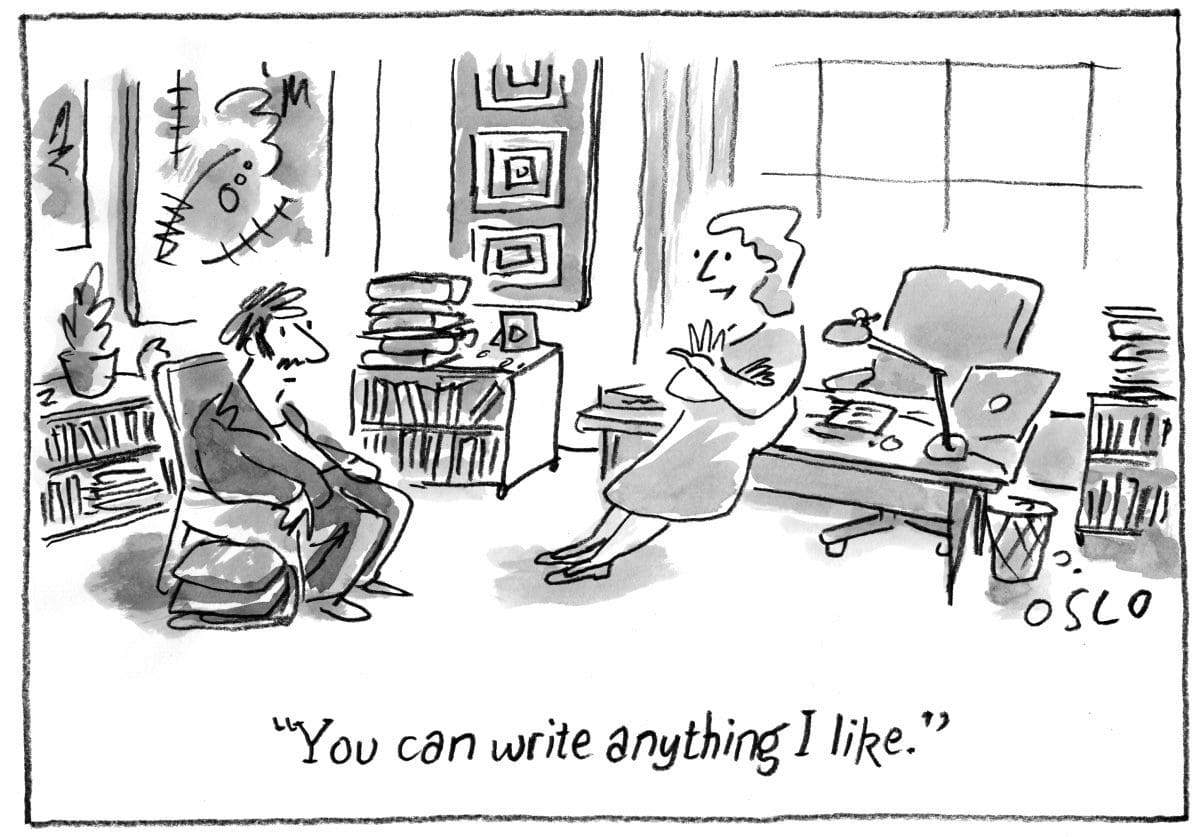

The offer to write on the artist’s work came with an attractive word rate attached. The essay was to be published in a catalogue for an exhibition to be staged in a high-profile situation. Not only was the work by the artist actually pretty interesting – and about which you could say quite a lot – the clincher was that I had total freedom to write anything I liked. So the answer was, of course, yes.

Essay written, emailed, and then: silence.

Word came back that the artist wasn’t too thrilled. The issue was that the essay didn’t repeat a closely rehearsed set of statements about the artist’s work that had appeared in just about everything that had been in various pop culture websites and art magazines. The choice was either to junk the whole essay or to rewrite it along the lines that the artist preferred. In the end I decided that I wouldn’t rewrite it and the artist’s gallery, which was paying the generous word rate, did the honourable thing and honoured the original agreement and paid, which was very much appreciated, thank you.

I understand that it was naivety on my part to let myself believe the whole “you can write anything you like” line, because in reality every art writer knows that as a paid contractor to the artist/gallery relationship you are required to follow the rules. And one of those golden rules is that once the narrative around an artist’s work is established you are required to repeat it often, and with conviction, until the narrative is tweaked or, on those rare occasions, changed completely. It’s no big deal, it’s just one aspect of being an arts writer and as much a testimony to the realities of how art media works as it is to the pragmatic decisions one has to take in order to make a living working in it.

As any reader of mainstream arts publications will know, the majority of art writing is not critical, it’s journalistic, which means it’s tied to the cyclical promotion of exhibitions, events and prizes that dot the art world’s annual calendar. Galleries – or more likely their PR people – will craft press releases and journalists, who work from those documents to write their stories, will do interviews for supplemental quotes, maybe they’ll even dress it up with a nice photo or two of the artist in their studio or smiling in front of their work. In the lucky dip of free media coverage the editorial decision about what gets covered is based on one simple question: What makes it newsworthy? And so we have the phenomenon of the artist’s backstory – a compelling personal narrative that gives the general audience some emotional connection to the artist and their work. It’s the reason why newspapers and TV arts documentaries love the artist profile story and have little time for a discussion of the actual art.

What’s interesting about the management of the critical aspect of the discussion about an artist’s work is that it’s widely believed that an artist should be the arbitrator of how their work is interpreted. To some degree I think that’s fine, but it places a limit on the potential for that work to have an independent life beyond the artist, their gallery, their estate or general critical consensus.

We know and accept that meaning is contextual and largely created by the audience, but that context has to come from somewhere.

The art world couldn’t function with people making up their own backstories or applying their own hairbrained theories to deciding what the art is about – and so we agree to agree.

That’s the odd thing about the art world: it likes to think of itself as a contest of ideas but for the most part it’s a kind of collusion on values and outcomes. If we’re all going to put so much time, energy and emotional commitment into it, then it all has to mean something, and that meaning has to be agreed upon. The problem there is twofold. First, there is the issue of the art that doesn’t fit into the newsworthiness angle – it just has to exist for its own sake and somehow find an audience to love it. Second, there are artists who have discovered how to make art that not only neatly connects to their backstory but also has an element of newsworthiness that always seems to grab the public’s attention. A lot of people blame the market for the apparent dumbing down of art but it’s more likely that the self-perpetuating system of promotion, art writing and criticism is as much to blame.

There is another possibility. I once wrote a catalogue essay to the exact specifications stipulated by the artist. The artist sent me highlighted paragraphs of previous essays and articles and links to particular readings. I wrote the essay, cited the facts as required, but the artist still rejected the essay. No reason was given but I suspected it might be because I’m a shit writer. But you can be the judge of that.