Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Biennale Curatorium. From left: José Roca, Artistic Director, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, Anna Davis, Curator, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Paschal Daantos Berry, Head of Learning and Participation, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Talia Linz, Curator, Artspace, Hannah Donnelly, Producer, First Nations Programs, Information + Cultural Exchange (I.C.E.), Barbara Moore, Chief Executive Officer, Biennale of Sydney. Photograph: Joshua Morris.

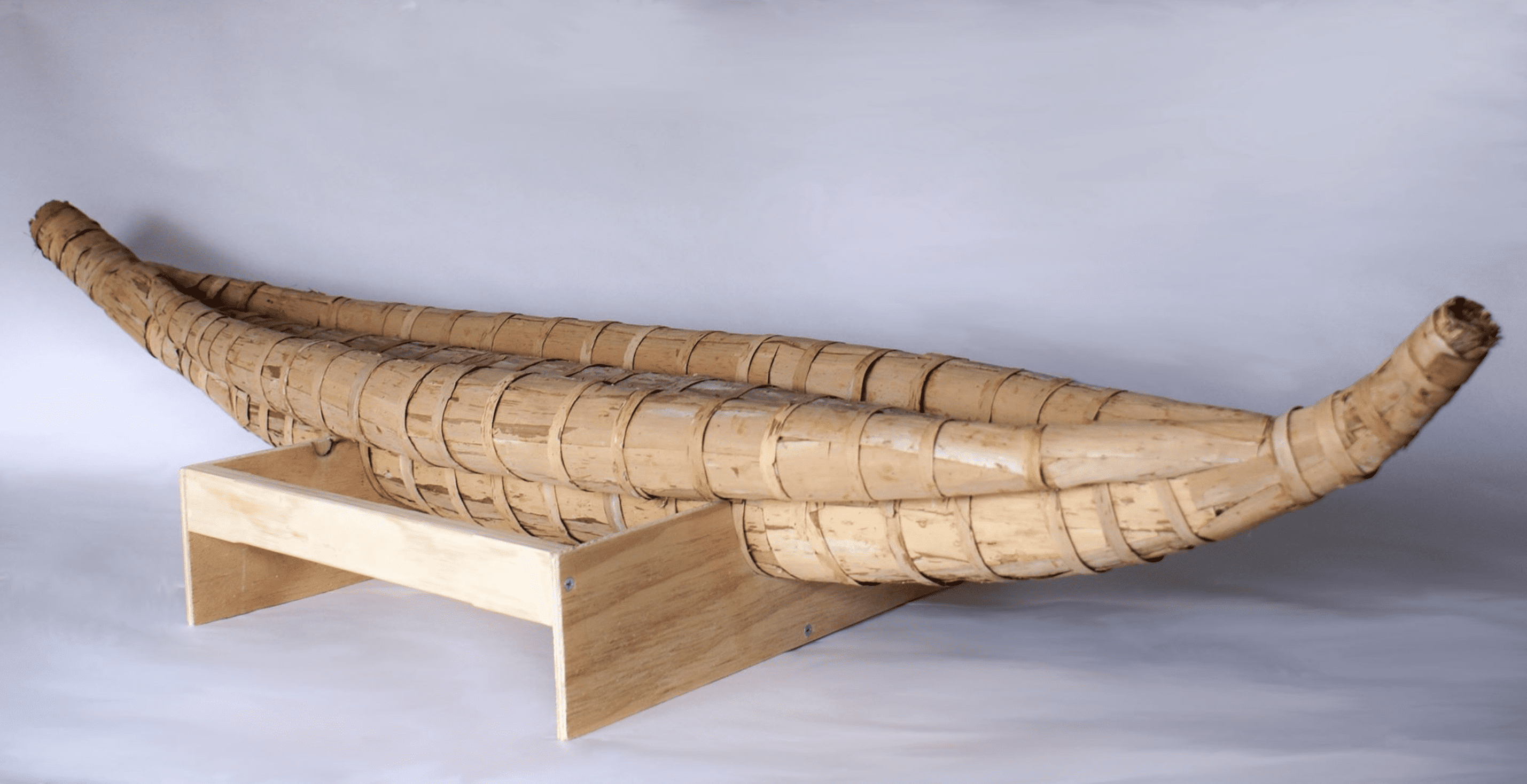

Julie Gough, Manifestation (Bruny Island), 2010. Installation view of Littoral (2010), curated by Vivonne Thwaites, Carnegie Gallery Hobart. Courtesy the artist. Photograph: Julie Gough. Copyright © Julie Gough.

Leeroy New, Rhizome Colony, 2017. Installation view for Wonderfruit Festival, Thailand. Commissioned by Wonderfruit Festival, Thailand. Photograph: Wonderfruit Festival. Copyright: Wonderfruit Festival.

Marguerite Humeau, The Dancers III & IV, Two marine mammals invoking higher spirits, 2019. Installation view at Centre Pompidou (2019), Paris. Courtesy the artist, C l e a r i n g new york/brussels. Photograph: Julia Andréone.

Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen: What is the significance of the Biennale’s theme rīvus?

José Roca: For many years, I’ve been interested in the relationships that art establishes with nature. As a curator, I’ve leaned towards that—for example, organising residencies in the Amazon jungle for the Sao Paulo Biennial back in 2006. When I was approached by the Sydney Biennale to do a proposal, I took this as a starting point. I proposed the idea of rivers and waterways and the communities that they sustain, and the project morphed into what it is now. Despite keeping the name rīvus, which suggests a relation to the river, it branches out into a delta of possibilities, including how we can collaborate with non-humans, the rights of nature and how they are enforced, and how a body of water can enter into productive dialogue with artists, designers, architects and so on.

Anna Davis: A river or waterway is constantly changing and flowing, and connected to other things, and this prompted us into a shift in perspective. De-centering the human was one way that we wanted to do that—looking at practitioners who have been working to bring forth the voices of more than human entities in their work, and looking at these kinds of issues beyond a human agenda.

JR: The Biennale is organised into conceptual territories that we’re calling wetlands. Each venue is a wetland or many wetlands, with different themes, relations between skies and the earth, assembled ecosystems, rewilding and caring for Country, saltwater ecologies and so on. We’re opting for a type of curating that does away with purity—we are not giving each participant distinct space, but rather, whenever possible, we have made the works to coexist in a somehow uncomfortable relation, to create a dialogue between them.

GAN: The Biennale has been curated by a curatorium. How did this process work?

JR: I moved to Sydney for the entire process to make it as local as possible. Even though I’m the artistic director and had the framework we started with, that has changed so much over the last year that I couldn’t claim it as my project. It’s a collective project that reflects our collective thinking. The curators have different backgrounds and ways of curating: some, like me, are more traditional curators in the sense that we work with artists and put together shows for institutions. Some are community organisers, working with communities on a smaller scale for a longer duration. They have the knowledge and are able to steer us in different directions. It’s a group of five people with different degrees of experience and interests that coalesce around a project, shape it differently and have produced something that reflects this connectivity.

GAN: Many of the artists participating this year are collectives. Was this a deliberate curatorial choice?

JR: We’re not using the word artists—we’re using participants, because not all of them consider themselves artists, and not all of them are even human. There are bodies of water that are invited as participants in the Biennale, as well as other objects.

AD: Our collective way of researching and curating as a curatorium has, perhaps naturally, led us to arrive at a number of collective processes as part of the Biennale. I personally think that some of the most powerful work is coming from artists working collectively across cultures and disciplines.

GAN: What is the idea behind non-living participants in the Biennale?

JR: There was a major legal milestone in 2008, when Ecuador enshrined the rights of nature in its constitution. Several rivers and bodies of water attained some degree of recognition and legal personhood. We thought, if they can have a voice in court, why can’t they have a voice in an exhibition? We have traditional custodians that can speak on behalf of the body of water. We’re calling them the river voices and they will be addressing the public directly.

AD: Another participant in the Biennale is an ancient fish fossil from Canowindra on Wiradjuri Country in New South Wales. It’s an incredible non-human document about river systems and fish that also brings up ideas about extinction, evolution, water precarity, and the connection that we all have to water. By talking about the voices of rivers and how you might engage with them, we eventually decided the fossil would also become one of the participants in the Biennale and be allowed to speak in its own way about these kinds of issues.

GAN: There is a greater focus on sustainability with this year’s Biennale—what are you doing to meet this goal?

JR: We took the idea of sustainability into how the Biennale is experienced by the public. We’re starting from a contradiction in terms—there is no such thing as a sustainable Biennale, because it’s about bringing the global to the local for a concentrated period of time. By definition, it is the contrary of sustainable. But we’re encouraging continuity, and we have been very conscious of the elements of perishable or temporary works after an exhibition ends, and the waste that the Biennale leaves after it ends. One of the components of that way of thinking is cultivating a Biennale that is more compact, that encourages people to visit by foot or public transportation. All the venues are close together, creating a path that can be experienced by anyone.

rīvus

Adelaide Contemporary Experimental

February 4 – March 18

This article was originally published in the March/April 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.