I’ve been thinking a lot about what constitutes a ‘real job’ the last few years. It’s not unusual to be asked what you do for money if you introduce yourself as an artist in Australia. And yet, the concept of ‘artists as workers’ isn’t a new, or particularly radical concept.

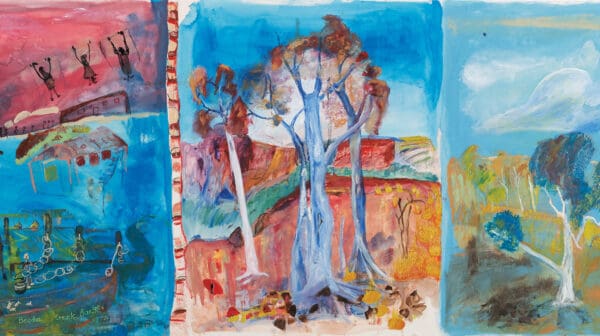

In my practice, I examine social hierarchies, memory, the value of craft, labour and female-dominated art practices. A few years ago, I started making a series of what I call labour plaques: ceramics that feature loaded words related to arts work like, “real job”, “hobby”, “grateful”, “patron”, “artist fee”, “sell-out”, “gig”, “Job Ready” and “unproductive potter”. This led to a 2020 article for the Journal of Australian Ceramics titled ‘Real Job’, and this year, a two-part curated group exhibition of the same name across Counihan and Seventh galleries in Melbourne, which explored working and funding conditions in the arts.

The central labour plaque from my ongoing series Don’t Quit Your Day Job was originally a hand-built ceramic platter I made for a small pottery business I planned to launch to support my art practice. I realised after an unfair work dismissal, dropping out of small business school, and a lot of soul-searching, that no, art isn’t my ‘hobby’. I added glass beads to the plaque and fired it, accidentally shattering the piece in the kiln. I later carefully glued the pieces back together, adding ceramic letters to spell out the phrase “REAL JOB”.

Yet to be considered real workers, it’s clear that artists and arts workers need fair pay, and support from governments and communities. I previously penned a piece about this for Art Guide—but what advances have happened in the sector since I last wrote about artists, labour and unions?

Associations and Organisations

Arts associations and organisations vary in their cultures and aims. Some focus on providing basic services that benefit their members such as insurance, exhibiting space and artwork sales. Others focus on advocacy and fighting for the rights of their members and the wider sector.

In recent times, the National Association of the Visual Arts (NAVA) has been moving in a more artist-as-worker direction. In 2022, over 8,000 people signed NAVA’s Recognise Artists as Workers petition, calling on the federal government to establish an industrial award for the visual arts, craft and design sectors that mandates standardised workplace entitlements. (you can still sign it here).

Outside of existing awards or Enterprise Bargaining Agreements, there are few legislated standards for professional working artists and arts workers. This lack of regulation often results in sham contracting where workers are unable to invoice for all hours worked or negotiate pay rates, are rarely paid superannuation, and risk adverse action for speaking up about workplace problems such as poor OHS and wage theft.

NAVA also petitioned the federal government to introduce or trial a basic income scheme for artists and arts workers to address the financial instability caused by gig work, and for Centrelink to recognise the professional work of artists and arts workers as employment-seeking activities, known as mutual obligations. Mutual obligations are activities, such as interviews and job applications, that welfare recipients have to do in return for their social security payment. Arts work that is unpaid currently doesn’t count as ‘real work’ or even volunteering according to Centrelink.

Yet when Tony Burke, the Arts, Employment and Workplace Relations minister visited REAL JOB at Counihan Gallery, he was surprised to hear from me that I was not paid any grants or fees for the considerable months of labour of putting on an exhibition with 16 artists and public programming across two galleries. Nor did Centrelink recognise my labour as mutual obligations.

This has to change. Smaller associations can empower arts workers to know their rights through education and campaigns. For example, in 2022, the Australian Ceramics Association published my article, Sham Contracting in the Ceramics Sector, uncovering the growing problem of bogus contracting within the art and craft industries.

This article alone has encouraged many small businesses to reform their practices, follow the Superannuation Guarantee, put ongoing contractors on the payroll, and to backpay unpaid wages or superannuation. But without funding, a change in legislation or union backing, individual advocates and associations can only do so much. Additionally, associations represent the interests of all their members, which may include unscrupulous employers or sponsors, resulting in a conflict of interest between the needs of workers and business-owners in the sector. Associations cannot provide the same level of support as a union to exploited workers.

Unions

Union coverage for arts workers and artists is patchy and inadequate, but there’s evidence this is changing. Council arts workers may find coverage in the Australian Services Union, university tutors in the National Tertiary Education Union, state government arts workers, such as National Gallery of Victoria employees, in the Community and Public Sector Union, and so on.

But what about arts workers in galleries or studios that aren’t covered by existing awards, EBAs or unions? Or visual artists themselves? The Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA) recently agreed to represent front-of-house staff at ACCA, who organised themselves and approached the union for support. If trusted arts associations partnered with existing unions, and an artists’ award were legislated, perhaps all visual arts workers could find coverage and assistance in a union. Even the union movement is starting to see art as work.

Government Policy

The federal government’s recent National Cultural Policy, Revive, embodies five pillars and principles. The third pillar, the Centrality of the Artist, states that as a society we should be “supporting the artist as worker and celebrating artists as creators”. At the policy launch at the Espy in Melbourne earlier this year, both Tony Burke and Anthony Albanese reiterated that “arts jobs are real jobs”, meaning workers are worthy of secure, fair and safe workplaces.

Currently public art galleries are not legally required to pay artist fees to their exhibiting artists, and some galleries even still charge artists to show. While artistic institutions and organisations provide spaces where challenging creative and political thought can be nurtured, these spaces are sometimes known to use marginalised groups to promote a diverse image, while exploiting the labour of the very groups they claim to support.

The federal government is also setting up the Centre for Arts and Entertainment Workplaces, geared at gig workers who don’t have industrial support, to address issues of pay, safety and welfare.

While there have been major advances in our attitude towards the arts after the pandemic and with a change of government, there’s still a long way to go before associations, unions, governments and our wider society truly see artists as workers.