Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

In an era that is saturated with visual information, photographs that change the way we see the world can feel increasingly elusive. As viewers, we are often seeking our reflection. But, often, the images that stand to transform society are those that unearth hidden histories, find a new language to articulate old problems or draw attention to the ethics of looking. We invited three acclaimed photographers to choose an image that challenges our assumptions about politics and culture during this historical moment—opening up new paths for their own work in the process.

The importance of truth-telling has never been more critical than it is now, when we are facing our increasingly precarious future. Given the constant rise of AI and misinformation in the media, I’ve found that—despite its flaws—photography has become a refuge to be able to speak your truth. I first saw We Were Just Little Boys, a 2023 photographic series by the Noongar and Spinifex visual storyteller Tace Stevens at the Centre for Contemporary Photography in March 2024. Stevens worked with survivors of the Kinchela Boys Home, a government institution that, between 1924 and 1970, removed hundreds of Indigenous boys from their families. An image from the series, They Will Never Erase Us, portrays two shadows that appear to be looking back on their past. The gloomy clouds are reminiscent of Australia’s dark history, reminding me that our future cannot exist without our past and that this is what we must learn from. The golden hour that lights the photograph shows the sun will shine even in the darkest of times, and the truth will come to light. Stevens’ work stuck with me long after I witnessed it. I’m inspired by the courage shown by the Indigenous men who stand strong in the face of such adversity. As an Indigenous person, people will still look into your eyes and tell you that you “need to move on”, despite Australia’s mournful history. Maintaining the strength to push back against this colonial and racist narrative is as crucial as ever. Photographers like Tace Stevens show us a clear way forward.

Kyle Archie Knight’s de-centre re-centre shows at Perth Festival, 15 February—3 May. His debut photobook Cruising for a Bruising is available from M.33, Perimeter Books, NGV Design Store and The Library Project.

Taysir Batniji’s 2024 series Disruptions features 86 screenshots made during a series of WhatsApp video conversations with the artist’s family in Gaza. Each image is marked heavily by digital distortion, fragmenting and tearing at the faces of Batniji’s loved ones. The screenshots, however, are not just disrupted by technical failure—they reflect connections shattered by Israeli forces of occupation, annihilation, and the constant surveillance that suffuse daily life.

Batniji transforms digital interference into a symbol of communication loss, where digital spaces—intended to bridge distances—become sites of rupture and absence. The image is flooded with radioactive greens and jagged blocks of blood-red. A portion of a ceiling can barely be made out in the top left corner of the photograph, a tiny but recognisable fragment. Perhaps a face is hidden behind a digital obfuscation, or a bedroom half-visible, offering an eerie trace of domestic life. The connection to love and home becomes fugitive. Batniji’s intentional use of low-quality resolution materialises the power of violence and separation to distort, infiltrate and deteriorate the last sites of intimacy during times of genocide and displacement.

In contrast with graphic images of bloodshed, Batniji underscores the role of abstract photographic representation, in contexts of violence and loss. Disruptions, which won Photobook of the Year at the 2024 Paris-Photo Aperture Awards, compels viewers to become sensitive to grief, and in doing so, more accountable for the injuries they see.

Amos Gebhardt’s Mångata shows at the Museum of Australian Photography until February 16.

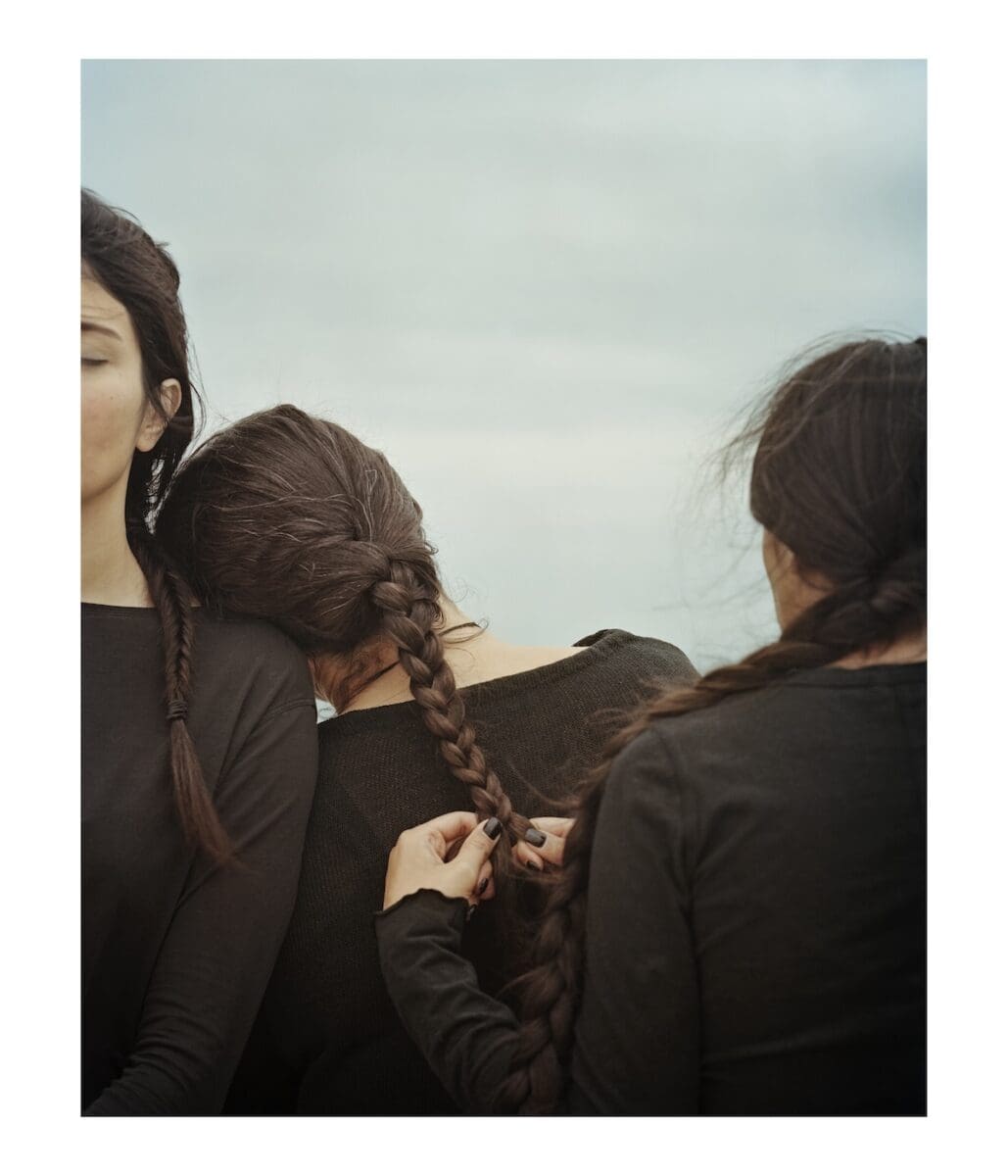

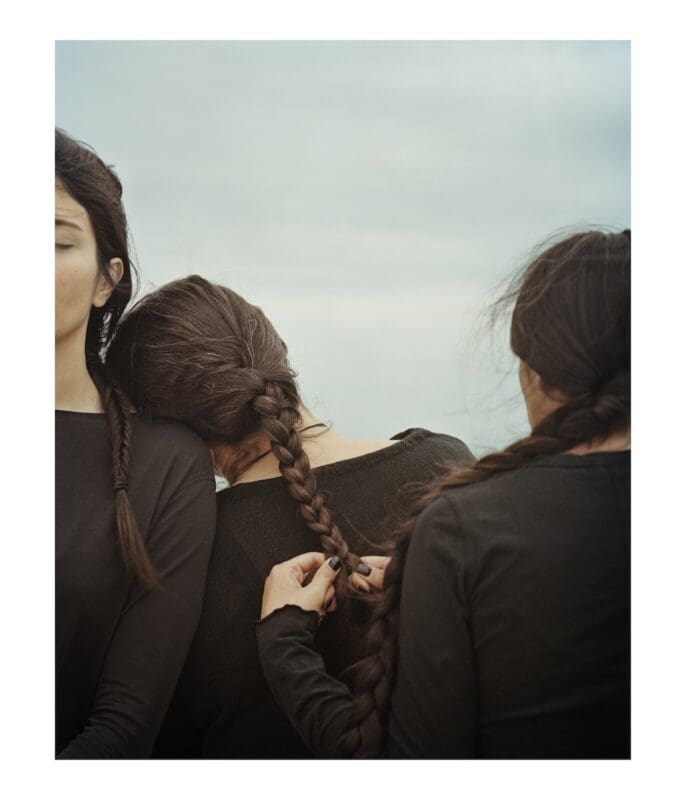

I chose an image from Hoda Afshar’s 2023 series In Turn. These images, which portray women braiding each other’s hair while doves take flight, refer to both Kurdish female fighters’ pre-battle rituals and tributes to fallen protesters. Rather than centering depictions of violence, they demonstrate how resistance can be captured through grace.

In her 2010 book The Cruel Radiance, writer Susie Linfield reflects on seeing a picture of Memuna Mansarah, a little girl whose right arm was hacked off just above the elbow by her compatriots in the so-called Revolutionary United Front (RUF) during the Sierra Leone Civil War. She speaks of her rage turning into pity and her pity, “so predictable and so useless”, turned into self-pity, meaning “Memuna herself began to recede”.

Unlike photographs of atrocity that can reduce viewers to helpless self-pity, Afshar communicates resistance through moments of vulnerability and reflection. She connects us to what Hannah Arendt places above pity—solidarity. To Arendt, this is not merely a feeling, but a principle for action.

Afshar made In Turn following the death of Mahsa Jina Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman whose death sparked the global “Women, Life, Freedom” movement. In doing so, she shows how staged photography can carry profound political weight through intimate gestures. When I look at the women’s closeness—their leaning heads, their gentle touch—I see the spaces between my own female familial relationships, and how colonial trauma might have fractured them. This year will see a possible first exhibition of my current body of work, which draws on performance and self-portraiture to investigate inherited trauma and its contemporary manifestations.

Isabella Melody Moore is an award-winning photojournalist.

This article was originally published in the January/February 2025 print issue of Art Guide Australia.